By Nicole LaBouff //

If you haven’t been to the Fountain Court at Mia to see the Blue Wash tapestries by Helena Hernmarck, now is the time. The four, 20-foot-long tapestries are due to come down in late July, and it could be years before they are on view again.

During the year that these works have been on view, visitors have sometimes asked me about them, usually along these lines:

Q: How were they made?

A: They were woven entirely by hand.

(Long pause.)

Q: How long did that take?

A: For all four tapestries, eight months.

Q: Did Hernmarck weave them by herself?

A: No. She worked with two assistants in her Connecticut studio to make two of the tapestries, the other two were woven at the studio of Alice Lund Textilier in Sweden. Hernmarck has collaborated with the Alice Lund weavers to make a number of her tapestries since 1975.

Few people ask about the materials used. Compared to the size of the tapestries, the substance can seem, well, immaterial. But woven into the work is a remarkable story, hiding in plain sight.

The dominant fiber is wool (the narrow warp threads are linen)—about 250 pounds of it courses through the thick bundles of weft threads running left to right in the four hangings. But this is no ordinary wool. It’s from a breed of sheep that once teetered on the edge of extinction.

Wålstedt family photo. Front left to right: Sven, Anna, Lasse, and Nils Wålstedt. Back row: Inger Wålstedt, Lars Warmenius (Inger’s husband), and Eva (Nils’s wife). Anne and Lasse spun and dyed the Blue Wash yarns in 1983. Photo: Helena Hernmarck, 1987

Hernmarck sources her wool yarn from a small factory in Dala-Floda, Sweden, founded by the Wålstedt family in the 1920s. Lennart Wålstedt established the operation during a revival of Sweden’s native folk textiles. The movement was led by artists and scholars, and some of them believed that to truly understand historic textiles, you need to make them. They wanted to use native Swedish rya wool for its unique textural qualities—the fibers are longer than other wool varieties and can have a glossy sheen to them. Rya wool was traditionally used for wall hangings and rya rugs, distinctive Scandinavian floor and bed coverings with long piles that could easily be mistaken for colorful furs or animal hides.

But Swedish wool was in short supply. In fact, it’d been disappearing since the 1800s, when sheep and wool from England began replacing local stock. Lennart Wålstedt scoured the surrounding Dalarna region for sheep that displayed native rya characteristics and could only acquire mixed breeds.

The rya sheep was essentially gone. But over time, Lennart Wålstedt purified his stock until he had a flock that was once again producing soft, lustrous rya wool. It is perhaps the only instance in which an animal was rescued by—and for—art.

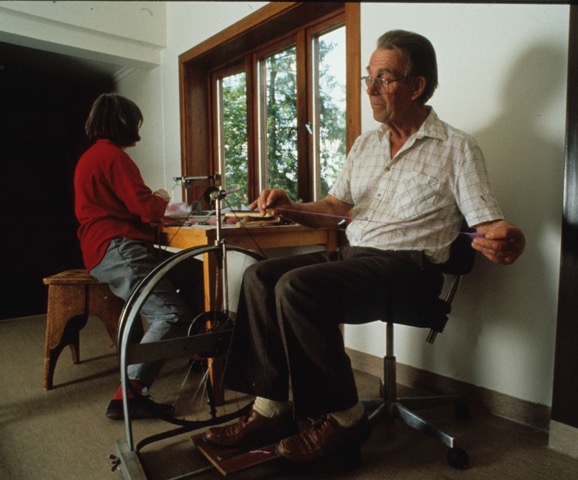

Lasse Wålstedt and Helena working out color samples for Springtime, commissioned for Atlanta’s C&S Sovran Bank. Lasse is spinning on a bicycle wheel turned spinning wheel that he invented. Photo: Staffan Björklund, © Dalarnas Museum, June 1991

Hernmarck began using Wålstedts’ wool at the start of her artistic career in Sweden in the 1960s and has never stopped. She has used it exclusively in virtually all of her 274 tapestries, working closely with three of the four generations of Wålstedt master spinners and dyers, who still use the spinning machinery built by Lennart’s son Lars in the 1930s.

Hernmarck is drawn to the unique textures of rya wool, the extensive color options that the Wålstedts factory produces, and the fact that they can produce yarn in large or small batches. But there is an important human dimension too: because the factory is small and family run, they work closely with their clients in a very collaborative way.

Helena at Wålstedts checking the plying of two threads for the Springtime tapestry commissioned by Atlanta’s C&S Sovran Bank. Photo: Staffan Björklund, © Dalarnas Museum, June 1991

In the 1970s, Hernmarck began making regular trips to the workshop so she could participate in the spinning and dyeing, making careful distinctions in the qualities and colors of the yarn she needed for upcoming projects. Hernmarck’s signature style as an artist and weaver hinges on these subtle variations in texture, thickness, and color of yarn—essentially her “artist’s palette.” In turn, as the leading customer for rya wool along with other Swedish individuals and ateliers, she is sustaining one of Sweden’s signature animals.

Hernmarck is well known for her deft handling of natural imagery: tulips, bluebonnets, landscapes, even Kermode bears. But we rarely talk about her use of natural materials and the impact her choices have had on the environment or other craft industries. I think we should.