An untitled painting by George Morrison, made in 1960, spent eighteen years lying on its back in storage—and for good reason.

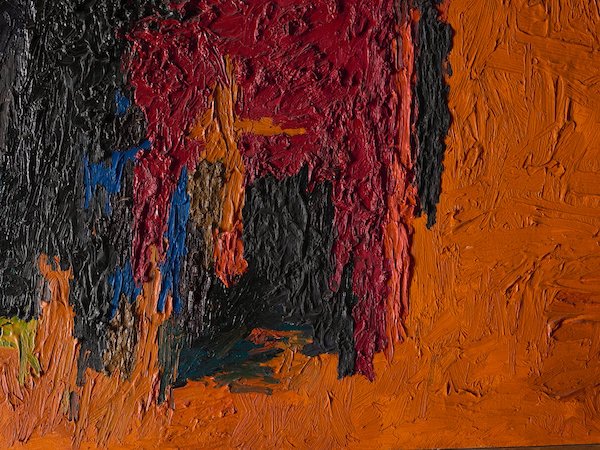

It certainly wasn’t unloved. The striking abstraction of an urban landscape had been hanging in an office at Mia for years, a favorite of one of the museum’s former directors. But in 1999, curators noticed that its condition was deteriorating. The painting had what is known in the conservation world as inherent vice: because of one or more of its intrinsic characteristics—in this case, Morrison’s thick, topographical paint strokes—deterioration and self-destruction of the painting was inevitable.

The paint was actually weighing down the canvas, and as the canvas aged it could no longer support the sheer weight of the paint on the surface. The more years it spent hanging upright, the more slack the painting became. Conserving it was too costly at the time. So into storage it went, lying down in order to prevent further damage, as though it had been laid to rest.

But in 2015, when Mia acquired another Morrison painting, the untitled work was suddenly resurrected. Curators Patrick Noon, Robert Cozzolino, and Jill Ahlberg Yohe decided to have the painting moved to the Midwest Art Conservation Center and they worked together to acquire funding for the necessary restorative work. Heather Everhart, curatorial department assistant for the Paintings Department, brought the project to the attention of previous Adopt-a-Painting sponsor Paula Vesely. Vesely, a long-time Morrison admirer, was delighted to help.

MACC already had the perfect person for the job. David Marquis had been working as a conservator with the Midwest Art Conservation Center for thirty-three years when the Adopt-a-Painting funds to restore Morrison’s work were procured right—before his retirement.

As it happens, Marquis not only admired Morrison’s work, he had taken painting classes with Morrison while an undergraduate. And when Marquis was earning his Master of Fine Arts at the University of Minnesota, Morrison served on his thesis committee. “If I had known when I was 25 that when I was 68 I’d be a conservator and working on one of George’s pieces, I never could have imagined that,” he said.

Morrison would pay graduate students to help move some of the large wood pieces he was working on in his studio, and Marquis was often among the hired help. “You know that wooden collage they’ve got up there?” Marquis said of Morrison’s beloved Collage IX: Landscape, a staple of Mia’s galleries. “I helped move that! Those things were so heavy.”

Morrison’s painting would finally be restored, but that didn’t mean it would be easy. The work’s inherent vice meant that many stages of restoration were necessary. “The paint was stronger than the canvas, so it started making the canvas deform and do what it wanted to do,” Marquis said. As a result, many passages of the painting were insecure and lifting, and required consolidation to prevent additional losses. And both consolidation and cleaning were challenging because of the thick texture of the paint. “In conservation, the painting always tells you what it needs,” Marquis said. “But before you proceed on any treatment, you test and retest.”

Over the course of about sixty treatment hours, Marquis reattached and consolidated areas of lifting and insecurity using a thermoplastic adhesive and controlled heat, filling in voids with pigments and wax. After the paint was secure, the highly textured surface was cleaned using a delicate “dry cleaning” technique normally used in paper conservation. The canvas was reattached to a new, heavier weight stretcher prepared with a “loose lining” for added support. Although the painting had not previously been framed, Marquis recommended it to further maintain the work’s structural integrity, and a design was chosen that stylistically matched other framed Morrison pieces.

For Marquis, it was serendipity—this would be his last project as a conservator. “It just felt right that I should be doing that,” he said. “I had a big personal as well as professional interest. After it had been in storage for so many years, I never thought I’d see that painting again. The odds of it happening at that particular time are pretty amazing.”

The painting is back on view, after eighteen years of rest, and Marquis believes it would have the Morrison stamp of approval: “I think he’d be proud to see it as it is now.”

Watch as Mia curators explain George Morrison’s unique and sometimes uncomfortable place between two worlds, the New York art scene and his native roots in Minnesota.