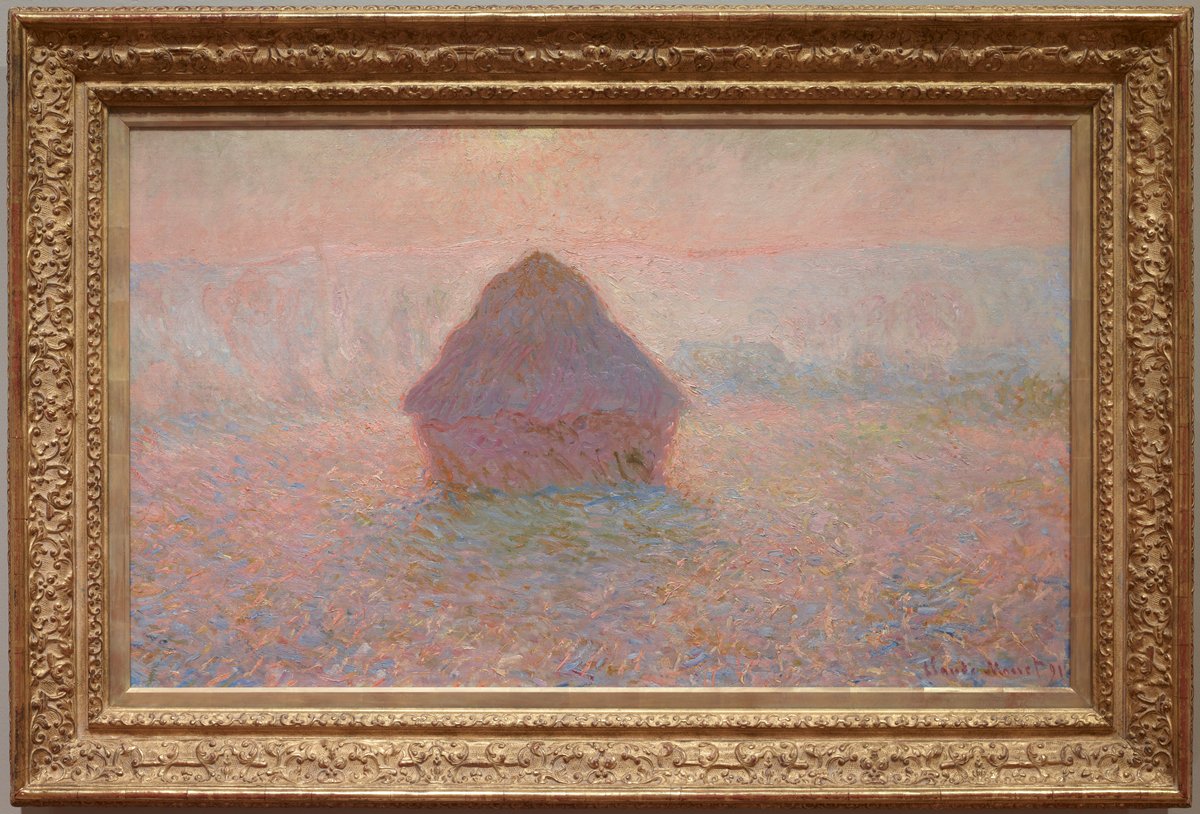

What do you notice when you look at a painting? Perhaps the composition strikes you first—the shapes, the colors, the lines. You might notice the depth created by thick or thin brush strokes. Then your field of vision zooms out and you notice the painting’s frame. Is it simple and unadorned, drawing attention not to itself but rather to the artwork inside? Is it big, gold, and garish? Does it beg as much of your attention as the item it’s framing in a way that feels triumphal, or maybe too obtrusive? You may ask yourself, is this frame the one the painting is supposed to be in?

Often the answer to that question is “no,” for a variety of reasons. Perhaps a painting’s original frame was removed and sold separately to accompany another artwork or a mirror. Maybe a wealthy patron who acquired a piece didn’t like its frame and commissioned a new one, which remained with the painting as it passed into a museum collection. There are many reasons why paintings you see in galleries may not be displayed in their original frames. If you want to view the painting in a context as close to the original as you can, a historically inappropriate frame could hinder that goal.

Which is exactly how Patrick Noon, Senior Curator of Paintings at Mia felt when he would look upon Claude Monet’s Grainstack, Sun in the Mist and frown. “It came to us in that frame,” Noon said, speaking of the gold frame that had accompanied the Monet in Mia’s galleries for decades. But it was a modern frame, overly decorative, and the color was totally inappropriate. “It was distracting because you couldn’t see the picture for the frame. You either make the frame aesthetically part of the ensemble or you make it recede so it doesn’t compete with the painting.”

Luckily, thanks to the generosity of Doug and Mary Olson, Grainstack is finding new life. The Douglas and Mary Olson Frame Acquisition Fund, started in 1997, began as an effort by Mia’s previous paintings curator, George Keyes, to replace frames in the collection with historically accurate ones, an idea that piqued the interest of Doug and Mary. “We became aware of how important frames were way back in the eighties and nineties,” Mary said, “We realized the museum had an unmet need: a fund specific for frames!” The acquisition fund was first put to use replacing the frame on Édouard Manet’s The Smoker.

But what of Monet’s Grainstack? Why was its dramatic frame with a detailed leafy motif inappropriate? According to Noon, nineteenth-century Impressionists like Monet weren’t exhibiting their work in the royally sanctioned Paris Salon to be purchased by wealthy patrons, but rather for art dealers who were catering to a new class of art buyers that was much more middle class. Traditional big art commissions from the church and state were disappearing, replaced by interested art buyers with expendable income looking to decorate their domestic spaces, not grand courtly palaces. French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel recognized the artistic potential of Impressionism early on, and established a market for it in Europe and the United States. To meet the needs of this new class of art buyers, he established a standardized Impressionist framing style. It was uniform for continuity, less expensive, and had much simpler designs. The function of Impressionist frames changed to suit this new paintings market.

But how do you find the right frame? Historically accurate impressionist frames aren’t exactly easy to come by on Amazon or your local craft store, so Mia contacted Paul Mitchell, a London-based frame dealer whose firm specializes in collecting and restoring antique frames. Paul’s son Mark visited the galleries with Noon in search of the next possible reframing project, and the Monet was an ideal candidate—the firm already had the perfect period appropriate frame in their stock. After some restoration and resizing work, the frame was ready to ship to Mia.

Jason Ressler, Framing Technician at Mia, gave me a sneak peek of Monet’s new frame. The Louis XVI oak and gold leaf frame, made in the 1700s and attributed to François-Charles Butteux, is actually nearly a century older than Monet’s painting. But Noon points out that with its minimal articulation of motifs, the frame is extremely close to what Durand-Ruel was producing for Impressionist paintings a century later.

The delicate process of reframing a priceless work of art is no easy task. “It’s a nervous responsibility,” Ressler said, “You can’t be too careful working on something like that.” As a framing technician, Ressler is handling not one work of art, but two. “It’s pretty nerve-wracking to drill into a board that happens to be on a frame that’s 240 years old. It’s a zen practice, because you have to be mindful and stay present in the moment.”

Framing technicians Jason Ressler and Sam Molstad remove the Monet from its original frame for storage.

Ressler’s efforts are all in the service of an ideal in which Noon, the Olsons, and Ressler himself strongly believe.

“It’s exciting when I see someone staring deeply at a painting I’ve framed. It’s a quiet moment I can enjoy, knowing they’re really seeing the painting, not some problem with the frame,” Ressler remarked.

Noon notes that these frames are extremely important pieces of furniture. “They served the very important function of making the art within it more accessible. They needed to meld with the environment they were in,” he said, “There are all kinds of reasons why these things were important beyond protecting the painting.”

As for Mary Olson, she’s excited by the subtle but important change the new frame will have on her experience of the painting.

“Most people look at a picture and they see what they see. But what you see is really affected by the frame. With the Monet, it really looks like a different painting! What I noticed so much more is it seemed there was more to it. More color, more variety. The frame it had been in was kind of a pink-gold, and there’s so much pink and lavender in the painting that that was really all you could see. Now you can see so much more depth, and it presents so much more animatedly. The right frame really makes the painting.”

Claude Monet’s Grainstack, Sun in the Mist is now on view in gallery 355.

Interested in contributing to the conservation of one of your favorite objects at Mia? Become an Art Champion today!