To celebrate Women’s History Month, we asked each of our curatorial departments at Mia to highlight works by women. You’ll find more, along with videos, stories, and related exhibitions on our Women’s History Month site.

Decorative Arts, Textiles, and Sculpture

Lucy: The 3.5 Million Year Old Lady by Faith Ringgold (American, b. 1930), 1977. Mixed media on wood and fabric.

Faith Ringgold’s sculpture was inspired by the 1974 discovery in Hadar, Ethiopia, of “Lucy,” a partial female skeleton belonging to an extinct species in human ancestry, Australopithecus afarensis. The find pinpointed, in both space and time, the shift to upright walking on two legs—a hallmark of human evolution. The news inspired Ringgold to travel to Africa in 1976. Fabrics she gathered on this trip, along with items acquired from her mother (a former fashion designer), were included in the sculpture. The work is reminiscent of an open casket containing an effigy of Lucy flanked by miniature vases, displaying fabric flowers.

In the late 1960s, Colombian artist Olga de Amaral embarked on a series of radical experiments in weaving, composing monumental sculptures consisting only of warp (vertical) threads using techniques akin to braiding. This body of work became known as her Muros Tejidos (Woven Walls) series. Here, earth tones and a lattice-like structure reference centuries-old Incan slit tapestries, indicating Amaral’s long-term interest in historical Latin American textiles.

Sylvia Stave was one of the most original Swedish designers in Stockholm in the 1930s. Working predominantly in pewter, brass, silver plate and, occasionally, silver, Stave’s designs for domestic wares—pitchers, teapots, vases, cocktail glasses—were distinguished for their purity of form, geometric volumes, and functionalist aesthetic. From the outset of her career, until she gave it up ten years later, Stave was celebrated, her work featured in exhibitions at home, across Europe and the United States. Yet she was entirely forgotten in the decades to come until 1989, when the Italian design firm Alessi reproduced her cocktail shaker in stainless steel— misattributing it to the Bauhaus designer Marianne Brandt, whose designs in the 1920s were distinguished for their spare geometries and machine aesthetic.

British East India Company – Trade & Colonise by Robin Best (Australian, born 1953), 2016. Porcelain, pigments, silver foil.

Since the early 2010s, Australian artist Robin Best has made her home in Jingdezhen, China, a city at the center of the porcelain industry for more than a thousand years. There, she has perfected a style of painting in miniature on porcelain. Best draws her subjects from historical narratives and imagery concerned with global trade and cultural exchange among Europe, South and East Asia, and Australia from the 1600s through the 1800s. These five vases are intended to be seen together and read as a story of British imperialism: they allude to the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and the subsequent rise of British naval power; the founding of the East India Company in 1600, which advanced Britain’s trade interests with India and China; and the exploration and colonization of Australia in the late 1700s and 1800s.

Japanese and Korean Art

Physarum by Mori Aya (Japanese, born 1989), 2017. Sculpture; glazed stoneware.

When Mori Aya created this sculpture in 2017, it was the largest piece she had ever attempted. Inspired by the branch-like form and slow, rhythmic movement of a type of slime mold called physarum, she built the dramatic, detailed form by hand and used a traditional namako (“sea cucumber”) glaze in deep, lustrous blue that drips to bright green and warm brown in the work’s crevices and folds.

Takemura Yūri took her inspiration for this bowl from an ancient myth about a struggle between two brothers, a fisherman called Umisachi (literally, “goes to the sea”) and a hunter called Yamasachi (“goes to the mountains”). Takemura reimagines this struggle between land and sea in the swirling, organic surface decoration of her bowl.

Paintings

Portrait of a Girl by Joan Brown (American, 1938–1990), 1971. Enamel and glitter on Masonite.

Portrait of a Girl is among Joan Brown’s most startling and engaging self-portraits—a memory picture, allegorical and mysterious. It was painted based on two photographs of Brown as a child. The Chinese dragon screen that looms behind her is based on a black-and-white illustration in a book that Brown owned. She took liberties with both her image and the screen, reimagining them and presenting them together to establish a tension between the two elements that provokes the viewer to muse on the relationship between Brown as a little girl and the menacing dragon. Brown was a virtuoso painter who moved fluidly from abstraction in the late 1950s through clean, crisp, large-scale self portraits in the 1970s. She tirelessly brought forth aspects of her persona and personal life in painting both imaginatively and in images drawn from actual events.

The confident, sensually painted subject of this painting is José de Guadalupe Mojica (1895-1974), an actor, accomplished opera singer, and eventually a Catholic monk of the Franciscan order. Mojica was among the first Mexican American film stars in Hollywood’s early years and was adored for his many talents across genres. Macena Barton likely painted him while he was working with the Chicago Lyric Opera and, with her own flair for theatricality, posed him in the costume he wore for his current role.

Art of Africa and the Americas

Traditional Zulu earthenware vessels function as potent connectors between ancestors and the living. Most are made for either brewing or serving mild beer, which is communally consumed at important occasions. Even though Zulu potters work within a traditional artistic canon of process, form, and surface treatment, there is considerable opportunity for individual expression. Indeed, distinguishing’s one’s pottery is a primary vehicle for women to assert and increase their prestige within Zulu society. Mncane Nzuza’s pots, remarkably accomplished both technically and aesthetically, are a testament to this dynamic.

In rural Morocco, Amazigh (Berber) and Jewish men both wore this type of cape, which offered multiple layers of protection. Woven of goat wool and hair by women working collectively, it enfolded the wearer in its warmth and shielded him from the elements in the Atlas Mountains. The large orange shape on the back symbolizes a dramatic eye, meant to protect the wearer from the harmful forces of the evil eye. Belief that someone’s malicious glare has the power to cause misfortune or injury is widespread among Mediterranean cultures.

Story of a Woman by Louise Erdrich (American, Ojibwe, born 1954), 2015. Acrylic on canvas, typed paper.

Hundreds of horizontal, blood-red, rhythmical lines appear on a stretched canvas, as though written by hand on paper. The canvas is accompanied by a piece of paper (part of the work), meant to be displayed with the canvas like a museum label, with the words “no baby” typewritten repeatedly in rows, and the words “yes baby” subtly and only sporadically interrupting this pattern.

Distinguished author and artist Louise Erdrich narrates Story of a Woman through painting and prose, with the same attention to detail, tone, and cadence found in her novels. Story of a Woman is a reflection of being a woman and bearing children, as represented by rhythmical brushwork and repetitive text. Together, they form a powerful and universal statement about the nature of womanhood.

Náhookǫsjí Hai (Winter in the North)/Biboon Giiwedinong (It Is Winter in the North) by D. Y. Begay (American, Navajo, born 1953), 2018. Wool and natural dyes.

In February 2018, Navajo textile artist D. Y. Begay traveled to Grand Portage, Minnesota, from her home in the Southwest to create this work. Begay’s textiles are abstract paintings on wool, drawn from her keen observations of specific landscapes, particularly within Diné Bikéyah, or Navajo land. In this instance, Begay spent days observing Lake Superior and its environs. Her attention to details, of the gentle mist, the light behind trees, and the vast winter sky, helps convey the serenity of the place itself.

Photography and New Media

Madame Mama Bush by Mickalene Thomas (United States, born 1971), 2012, Chromogenic print. © Mickalene Thomas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

This brilliantly hued photograph depicts the artist Mickalene Thomas’s mother, Sandra, at the artist’s studio. Deftly instrumentalizing iconographic tropes—figurations of the muse and of the odalisque—she presents a fundamental shift in the visualization of black female bodies and their power. Sandra’s gleaming breast, her vivid robe, the sensuous curve of her legs as they drape across the flowered and animal-patterned draperies of her couch, and above all her profile, turned to the ceiling in rapturous repose, claim the space within the frame as hers alone.

Monument, General P.G.T. Beauregard, New Orleans, Louisiana, by An-My Lê (American, born 1960), 2016. Inkjet print. © An-My Lê

An-My Lê explores the environmental, psychological, and cultural impacts of war upon landscapes and people. Taken as part of a larger series exhibited at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, Monument engages critically with the historic visual culture of American armed conflict. The uncanny results of her camerawork are landscapes that appear to be poised between the world of dreams and that of reality; by destabilizing the boundaries between the nightmare of war and its representations or rehearsals, she demonstrates the precise thinness of the scrim between peacetime and crisis, civilian and military life. At the same time, and through her imaging of a shrouded monument to the Civil War, she illuminates the ongoing and unsettled nature of key areas of conflict in American society, including matters of race, class, labor, and wealth, and signals an alternative historical narrative for our consideration.

Prints and Drawings

Resurrection Story with Patrons by Kara Walker (American, born 1969), 2017. Published by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York; edition of 25. Etching with aquatint, sugar-lift, spit-bite, and drypoint; triptych.

Resurrection Story with Patrons expands on Kara Walker’s celebrated repertoire of cut-paper silhouettes of the antebellum South with a narrative triptych, a pictorial format common to the Christian altarpiece tradition. Though best known for her uncompromising depictions of the horrors of slavery in the United States, here Walker presents a message of hope and redemption, albeit within an ambiguous and contradictory narrative that poses as many questions as it answers. The central panel depicts a seaside scene in which several small silhouetted figures use ropes to raise an excavated colossal statue of a naked black woman. In the side panels, a male and a female figure wearing 18th-century attire appear in reverse silhouette, signifying the patrons who would typically appear in a traditional altarpiece commission. Walker unifies the scenes with slanting timbers that traverse the triptych and may reference the carried cross, the wrecked frames of a ship, and architectural beams. With references to Christian iconography and martyrdom, Walker engages the viewer to reflect on the current state of racial relations in the United States.

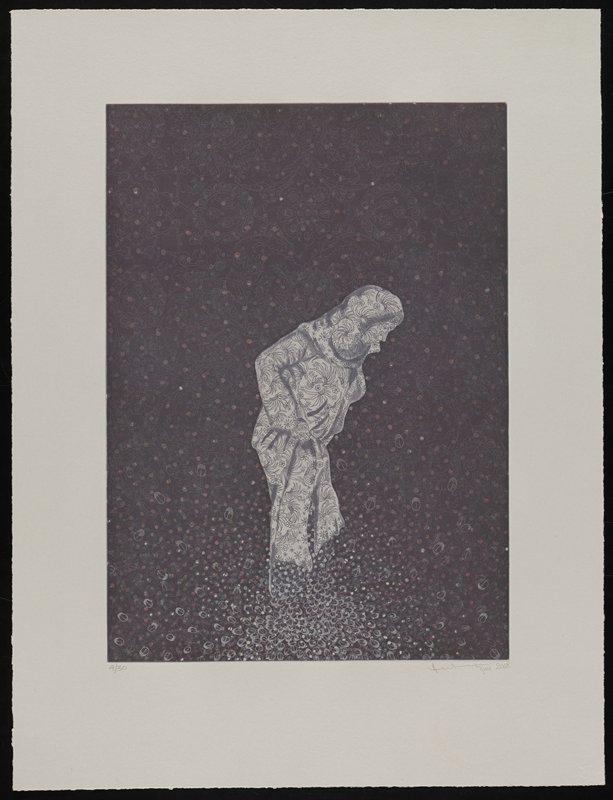

Daughter of the East suite of five prints by Ambreen Butt (Pakistani, active United States, born 1969), 2008. Color etching, aquatint, spit-bite aquatint, drypoint, and chine collé. Published by Wingate Studio, Hinsdale, N.H.; edition of 30.

Ambreen Butt’s Daughter of the East memorializes the scores of young women and girls who died in a violent confrontation between Islamic fundamentalists and the Pakistani military during the July 2007 siege of Lal Masjid, or Red Mosque, a conservative center of religious teaching in Islamabad. Most victims were students at the nearby Jamia Hafsa madrasah complex. The mosque’s clerics opposed the Pakistani government’s social and economic liberalization and called for the overthrow of President Pervez Musharraf and the imposition of traditional sharia law. Inspired by the tradition of Indian and Persian miniaturists, Butt created a series of highly detailed images that, paradoxically, are both decorative and disconcerting. This seeming contradiction mirrors the event’s complicated narrative of fear, violence, vulnerability, and resilience among the women and girls who remained true to their religious beliefs but were reportedly used as human shields by armed male defenders of the mosque.

The Study of Drawing: Portrait of Yves Osterlind, Age Nine, by Louise Catherine Breslau (Swiss, born Germany, active France, 1856–1927), 1901. Pastel on paper.

The celebrated Impressionist artist Louise Breslau was a trailblazer. She moved to Paris from Switzerland at the age of 19 to study at the Académie Julian, one of the few schools open to female students, and the only place in Paris where women could study the nude model. Breslau led an illustrious, lucrative career as a portrait and still life painter. She exhibited frequently at the Paris Salon and across Europe, and she was the first foreign female artist to win prestigious distinctions in France, including a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle (1889), the first to serve on a Salon jury (1893), and the first to be awarded the Legion of Honor (1901)—the year this work was executed.

Her portraits of children were particularly celebrated. Here she portrays Yves Osterlind, the child of her friends, the Swedish painter Allan Osterlind and French watercolorist Eugènie Carré Osterlind. Yves grew up to become a printmaker, despite his father’s worries, expressed in letters to his wife, that he did not draw enough and laziness would keep him out of art school. Breslau depicts the boy, age nine, if not quite lazy, perhaps unfocused. As he sharpens his chalk, he looks out at the viewer with a distracted glance. His desk is in disarray, with papers and drawing utensils strewn about and a half-eaten orange set aside.

receipts, glass [jockey] by Stacey Davidson (American, born 1961), 2018. Oil on prepared paper mounted on panel.

Mother and Child by Mary Cassatt (American, 1844-1926), 1894 . Drypoint and aquatint printed in color, with monotype inking and touches of brushed-on color .

The American expatriate Mary Cassatt played a central role in Paris’s progressive art scene, beginning with her appearance in the Impressionist exhibition of 1879. Though she initially scorned printmaking, Cassatt grew to love its rigor and endless possibilities. In color printmaking, she developed a fusion between the abstract graphics of Japanese color prints and the atmospherics of Western art. Looking at this print, we hardly notice the complex process that required multi-stage development of three separate copper plates; instead, we marvel at the rich, freely-applied color of this tender scene.

The Soaring Hour (Self Portrait) by Delita Martin ( American, born , 2018 ). Relief printing, charcoal, acrylic, colored pencil, decorative paper, and hand-stitching on paper.

Delita Martin’s colorful works combine printmaking, drawing, and painting to celebrate African American women as icons of strength and community. Finding inspiration in oral traditions and vintage and family photographs, Martin’s work explores the art of storytelling. By depicting her subjects as matriarchal symbols, she offers greater understanding and appreciation for the role of African American women in their families and communities. Her most recent body of work, the series “Between Spirits and Sisters,” is inspired by the Sande society of West Africa’s Mende people, an exclusive community of women that prepares Mende girls for their transition into womanhood. In her self-portrait, The Soaring Hour, Martin addresses her own dual existence between the physical and the spiritual. “The duality of women in this body of work project the spirit and its connection to the physical world, which reinforces the bond amongst women and how they co-exist in the physical and spiritual realms. The mask seen in the work is my interpretation of the Mende mask, specifically created for young girls being initiated into Sande. These masks are created as a reminder that human beings have a dual existence viewed as one body.” —Delita Martin, 2018

Chinese, South and Southeast Asian Art

Homes I Made / A Life in Nine Lines, by Zarina Hashmi (Indian, born 1937), 1997. Portfolio of nine etchings and a cover sheet printed in black on Arches Cover white paper and chine-colle on Nepalese handmade paper.

Zarina Hashmi, who goes by Zarina, vividly recalls her early childhood in India: the fragrances of the garden, the clarity of Mughal architecture, and, in 1947, “the smell of rotting flesh” as her family temporarily fled to Pakistan during Partition, when British-controlled India was divided after independence along Hindu and Muslim religious lines into India and Pakistan, displacing an estimated ten to twelve million people and leaving up to a million dead in sectarian violence. The event set the course for the artist’s highly mobile life, as well as her preoccupation with the power of memory and the centrality of home. In this suite of nine etchings, the artist traces her journey from Bangkok, Thailand, to New York, chronicling her literal “homes” as well as her artistic development working in many of the late 20th century’s leading avant-garde circles, including Stanley William Hayter’s Paris-based print studio, Atelier 17. In this work, the portfolio’s cover sheet features a small compass with the directions marked in Urdu, the artists’ mother tongue, and a language (and culture) slowly diminishing in India.

Bethlehem by Monika Correa (Indian, born 1938), 2012-2013.

Unbleached cotton, handspun dyed wool.

For more than five decades, the Mumbai-based fiber artist Monika Correa has sensitively experimented with the structural and emotive possibilities of weaving. Her early interest in collecting handwoven traditional Indian silks was transformed upon first seeing the colorful, tufted wool of Finnish rya (rugs) on a trip to Scandinavia in 1962. After a brief but life-changing tutelage with Marianne Strengell, former head of the textile department at the Cranbrook Academy of Arts, Correa was given parting gift from the master teacher: working drawings for a custom handloom, which Correa constructed in her Mumbai living room and where it still presides today.

Correa is Roman Catholic by way of Goa, the former Portuguese enclave in western India that has long had distinct Goan Catholic community. When asked about the title of this piece, she explains: “I had run out of wool and sent for some from Panipat [Harayana, India]. It usually comes in a natural off-white, which I then get dyed to the colours of my choice. But this time, the supplier sent natural white wool handspun with streaks of natural beige-brown wool, almost straight off the back of the sheep! It was Christmastime, December. For some unknown reason, my thoughts went to the sheep I was just beginning to put together for the Nativity Creche, and I decided to work on this natural wool which I teamed up with the Reds and Pinks and Orange wool that I had. Then I added the Star of Bethlehem (orange tuft visible on the centre left of the tapestry). This tapestry gave me a lot of peace—another reason for the name ‘Bethlehem,’ peace to the world.”

Good Fortune and Longevity by Empress Dowager Cixi (Chinese, 1835–1908), 1902. Ink and color on silk.

Empress Cixi was also an artist. She created this scroll of peony blossoms by applying graduated washes of color rather than drawing them as ink outlines. This is a hallmark of the mogu, or “boneless,” painting method, which is ideal for conveying the delicacy and coloring of flower petals. The peony has been hailed as the king of flowers in China for its majestic scale, fragrance, and literary associations. Its rich colors and abundance of petals have linked the peony to nobility and wealth. These associations, as well as the inscription of good fortune on this painting, would have made the artwork a prestigious and auspicious gift from Cixi to a relative or courtier.

Contemporary Art

Cosmic Generator (Lettuce Variant) by Mika Rottenberg (Argentine-Israeli, born 1976), 2017. HD video (single-channel, 27 minutes), sculptural elements. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Exploring the seduction, magic, and desperation of our hyper-capitalist, globally-connected reality, Mika Rottenberg’s elaborate visual narratives draw on cinematic and sculptural traditions to forge a new language—one that uses cause and effect structures to explore labor and globalization, economy, and production of value, and how our own affective relationships are increasingly monetized.

Like many of her recent works, Cosmic Generator incorporates documentary footage into a framework of characters working in nonsensical economies. For this project, Rottenberg uses real footage of dollar stores in Calexico, California; Mexicali, Mexico; and Yiwu, China, to recreate the imaginary life of a product from production to sale. The segments are regularly interrupted by depictions of surreal tunnels, which according to the artist represent the structures that Chinese residents of Mexicali supposedly dug under their homes and shops to travel surreptitiously to Calexico.

Shelves for Dynamite by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (British, born 1977), 2018. Oil on linen. © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Corvi-Mora, London.

Writer and painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye creates figures from imagination and memory that deliberately distance the viewer from any personal narrative, time, or place. According to Yiadom-Boakye, her painting and writings—short stories, poems, and the titles of her paintings—work in parallel to one another to allow space for one’s imagination to flourish. She describes her fictional subjects as “suggestions of people. … They don’t share our concerns or anxieties. They are somewhere else altogether.” While rooted in traditional portraiture—her subjects are often arranged in poses drawn from the history of European and Euro-American art—Yiadom-Boakye’s process is decidedly contemporary, her paintings typically completed in a day to best capture a moment or her stream of consciousness.

Untitled (Como Park Conservatory) and Untitled (Portrait), from the “After the Fall of Hmong Teb Chaw” series by Pao Houa Her (American, born 1982), 2017. Archival inkjet print.

The series “After the Fall of Hmong Teb Chaw”—or Hmong country—expresses the sense of displacement felt by some Hmong Americans in Minnesota. From 2014 to 2016, some Hmong elders were conned into investing in a fraudulent scheme called Hmong Teb Chaw. The victims were promised resettlement with benefits in a new Hmong nation-state. The fallout from the scheme revealed the generational divide between those who remember living in Laos and hope to return and younger generations who were born and raised in the United States.

Her’s photographs capture her subjects against backdrops that conceal the setting, a center for Hmong elders in Minnesota. The backdrop also recalls traditional Southeast Asian portraiture where subjects are placed in front of idealized settings with artificial foliage. The portraits are paired with photographs of the Como Park Conservatory in Saint Paul, an ersatz environment of lush, tropical plants reminiscent of Laos. In Her’s series, the setting may be fake but the subjects’ yearning and hope are real.

Reconstructing an exodus history: flight routes from camps and of ODP cases by Tiffany Chung (Vietnamese, born 1969), 2017. Embroidery on fabric.

This work, from 2017, consists of an intricately embroidered world map with numerous dotted pink lines sewn in that crisscross the globe on a black fabric background. Each of these lines represent a flight route associated with the Orderly Departure Program (ODP), which oversaw the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees from 1980 to 1997 under the auspices of the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Approximately 623,000 Vietnamese individuals were resettled abroad as part of this program globally, of which roughly 458,000 came to the United States. As with much of Chung’s cartographic work, each map contains a complex system of coding along with explanatory legends that are often informed by what is missing: the voices and memories of these landscapes’ inhabitants. Chung takes on the role of ethnographer and historian to further document what the cartographic records and statistics cannot, the lived experiences and personal accounts embedded in these topographies.

Top image: One of five images in Ambreen Butt’s Daughter of the East suite from 2008. Color etching, aquatint, spit-bite aquatint, drypoint, and chine collé.