Self-Guided Tour

Celebrating African American Art

This self-guided tour invites you on a journey through the museum’s galleries to explore the depth, creativity, and cultural power of African American art. The artworks featured in this tour honor community, memory, resilience, and the ongoing story of African American experiences in the United States.

As you move through the galleries, we hope you’ll slow down and really look. There is no right or wrong way to experience art—just your way.

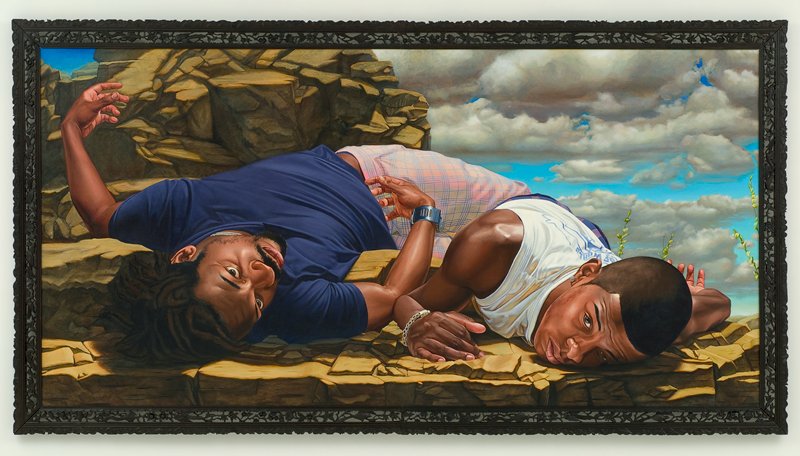

Kehinde Wiley: Santos Dumont – The Father of Aviation II, 2009 (Gallery 280)

Kehinde Wiley, United States, 1977. Santos Dumont – The Father of Aviation II, 2009, Oil on canvas. Gift of funds from two anonymous donors, 2010.99, © 2009 Kehinde Wiley

Kehinde Wiley is known for his large-scale portraits of Black men posing as kings, prophets, saints, and other celebrated figures in the tradition of the Old Master paintings of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. In placing Black bodies into the traditional settings of European portraiture, Wiley challenges racial discrimination in the art world and raises issues of identity and self. The subjects here are posed as two of the “fallen heroes” in a well-known public monument to Brazil’s pioneering aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont. By depicting his anonymous subjects as aviation heroes, Wiley immortalized two young Black men in oil paint.

Henry W. Bannarn: Cleota Collins, 1932 (Gallery 302)

Henry W. Bannarn, American, 1910-1965. Cleota Collins, 1932, Plaster, pigment. Gift of funds from the Decorative Arts, Textiles, and Sculpture Affinity Group 2011.64

When he made this portrait of the singer and civil rights activist Cleota Collins, in June 1932, Henry Bannarn was studying at the Minneapolis School of Art (now the Minneapolis College of Art and Design). It is his earliest known work. Born in Oklahoma, Bannarn had moved with his family to Minneapolis while still a child. Thanks to a grant from the Minnesota philanthropist James Ford Bell, Bannarn was able to move to New York, where his studio at 306 West 141st Street became a creative center and meeting place for African American artists, musicians, and poets. Within the movement known as the Harlem Renaissance, Bannarn became famous for his paintings and sculptures and was admired as a teacher and a mentor to younger artists.

William Edmondson: Ram, 1938–42 (Gallery 304)

William Edmondson, Ram, 1938–1942. 2013.56.

William Edmondson was a stonemason’s assistant in Tennessee when he felt a calling from God. He recalled, “I was out in the driveway with some old pieces of stone when I heard a voice telling me to pick up my tools. … I looked up in the sky and right there in the noon daylight … God was telling me to cut figures.” Edmondson began carving cast-off limestone blocks around 1933; four years later he was the first Black artist to have a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Ram shows Edmondson’s skill in abstracting natural forms, his powerful minimalist style, and the rich spiritual symbolism that brought him renown.

Lola Pettway, “Housetop” variation quilt, 1970s (Gallery 304)

Lola Pettway, Housetop variation quilt, 1970s. Corduroy. The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund and Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection 2019.16.16 © Lola Pettway / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The “housetop” quilt design repeats concentric squares, like rooftops seen from above. Lola Pettway used a red square to anchor her composition, from which nine concentric squares of avocado green, tomato red, gold and brown vibrate outward. Strips of red and green corduroy edge the beige panel. Lola Pettway’s mother, Allie Pettway, and the Freedom Quilting Bee of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, influenced Lola’s work. In 1972, the Freedom Quilting Bee secured a contract with Sears, Roebuck & Company to produce pillow shams, and the department store supplied materials to the quilters. Allie would have brought home unused material, accounting for Lola’s use of corduroy in quilts from this period.

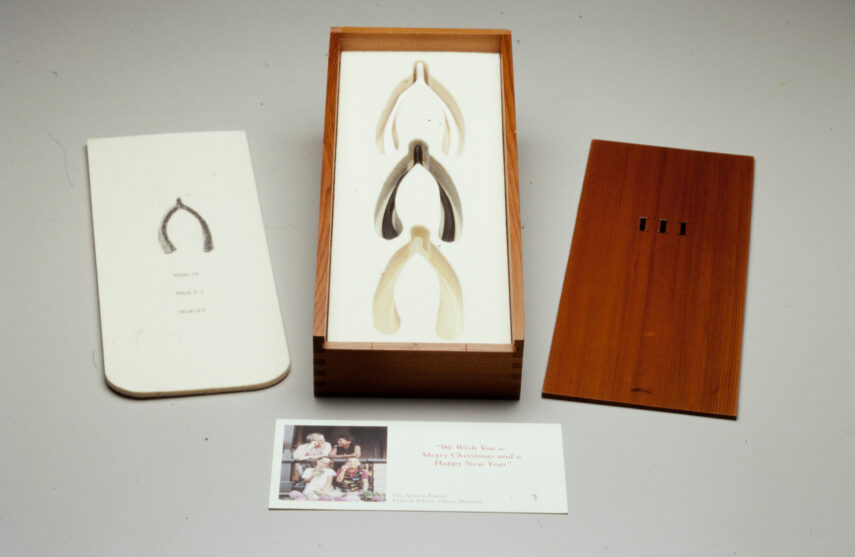

Lorna Simpson: III (Three Wishbones in a Wood Box), 1994 (Gallery 369)

Lorna Simpson, American, born 1960. III (Three Wishbones in a Wood Box), 1994. Peter Norton Family Christmas Projects, Pasadena, California, Publisher. Gift of Evan M. Maurer in honor of Denise May. 96.132a-c. © 1994 Lorna Simpson

Throughout her career, conceptual artist Lorna Simpson has explored topics related to gender, race, and history. The human body is often the focus of her explorations, both its strength and vulnerability. These three wishbones, presented like jewels or relics in a sleek wooden box, underscore the fragility and preciousness of human beings and their dreams. They also might suggest, based on Simpson’s choice of materials—ceramic, rubber, and bronze—that some wishes are easier to fulfill than others.

Note: This artwork is on view until February 14, 2026.

Emma Amos: Out in Front, 1982 (Gallery 369)

Emma Amos, American, 1937–2020. Out in Front, 1982. Handwoven cotton, synthetic, and metallic fibers with pigments on linen. Gift of Mary and Bob Mersky. 2020.44.1. © Emma Amos / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Emma Amos’s work was shaped by a wide range of influences, including modern western European art, the gestural energy of Abstract Expressionism, and the social urgency of the Civil Rights Movement and feminism. These diverse sources informed both the visual language and the political commitments of her practice. Color functioned not merely as an aesthetic choice but as a central conceptual tool. For Amos—who identified as a mixed-race African American woman—color carried layered personal, cultural, and historical meanings. Her sensitivity to these nuances led her to use color as a way of questioning identity, interrogating power structures, and challenging assumptions about race and representation in art. This engagement with color and identity is especially visible in her 1982 weaving-collage Out in Front.

Note: This artwork is on view starting February 14, 2026.

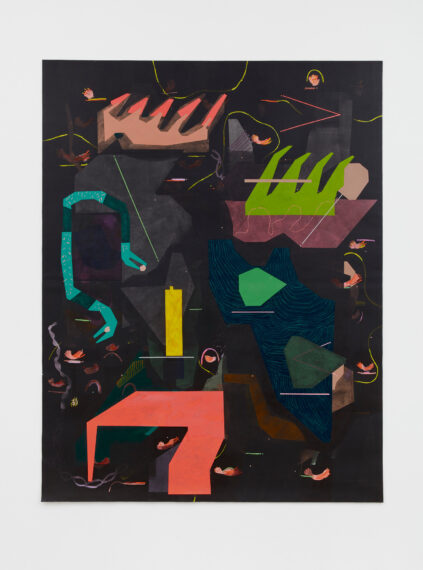

Caroline Kent: A forecast told through shadows, 2021 (Gallery 369)

Caroline Kent, American, born 1975. A forecast told through shadows, 2021. Acrylic on unstretched canvas. Gift of funds from Mary and Bob Mersky. 2021.44

Even as a child, Caroline Kent was immersed in the language of abstraction. Kent grew up alongside her identical twin sister, Christine Leventhal, with whom she shared special methods of communication. A forecast told through shadows is emblematic of Kent’s unique visual vocabulary and approach towards abstraction. The artist calls these works, which look a little like night-scenes by way of Hilma af Klint, “midnight canvases.” The works are metaphors for the undefined liminal spaces of our memories. Layered on top, as if free-floating in space, are pastel shapes, lines, and textures that conjure, she said, “things that might have at one time been covered in darkness but have now been illuminated.”

Note: This artwork is on view starting February 14, 2026.

Nick Cave: Soundsuit, 2010 (Gallery 373)

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2010, metal, wood, plastic, pigments, cotton and acrylic fibers. Gift of funds from Alida Messinger © Nick Cave and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY

Nick Cave makes his Soundsuits from scavenged cast-off goods. While the Soundsuits work as freestanding sculptures, Cave makes them to be worn; he has staged live performances in which the Soundsuits become moveable artworks. Cave created his first Soundsuit in the early 1990s in response to the beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police and the subsequent riots. The Soundsuits are often described as a protective armor, a “second skin” that allows the wearer to conceal their own identity in a fusion of costume, sculpture, and performance.

Note: This artwork is on view until February 14, 2026.

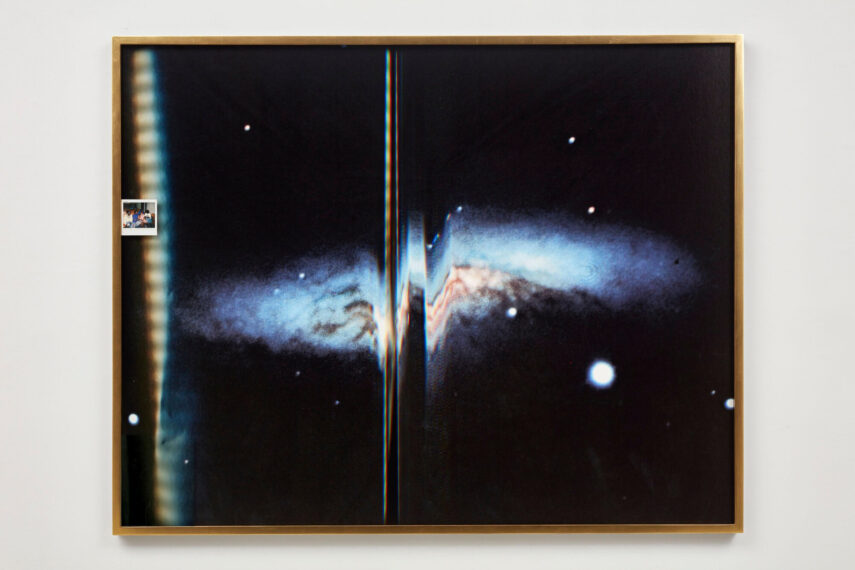

Deana Lawson: Messier 81, Return of the Dove, 2018 (Gallery 373)

Deana Lawson, American, born 1979. Messier 81, Return of the Dove, 2018. Pigment print, collaged photograph. Gift of Mary and Bob Mersky. 2020.44.2

Deana Lawson’s photographic assemblage presents the collapsing edges of a blue-and-pink galaxy. At far left a flowing, prismatic ribbon of light runs from top to bottom. A small snapshot of young Black churchgoers is tucked into the frame. By combining the everyday with the cosmic and centering the galaxy (whose dove-like shape alludes to the Holy Spirit, a manifestation of the Christian God), Lawson has created a universe of cultural meaning and spiritual significance. As a visualization of the Black diaspora, the galaxy is at once a metaphor for dispersal and connection and an image of divine intervention and protection.

Note: This artwork is on view until February 14, 2026.

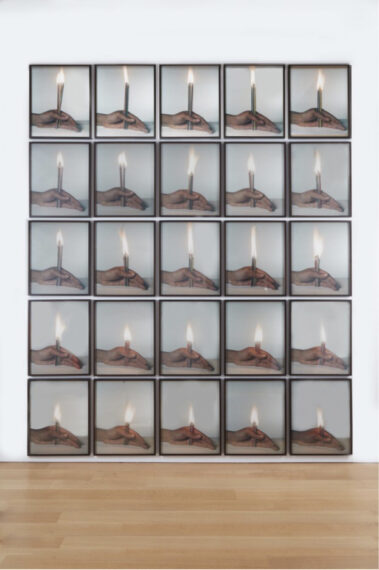

Lorna Simpson: Untitled (Six Candles) (Gallery 373)

Lorna Simpson, American, born 1960. Untitled (6 Candles), 1992. Color Polaroid prints. The John R. Van Derlip Fund. 2025.44a-y

The scale of Lorna Simpson’s Untitled (Six Candles) is deliberately monumental. Created during a residency with the Polaroid Foundation at the height of the AIDS epidemic, the artwork reflected Simpson’s grappling with “death and absence, using candles to reflect the passing of time.” Simpson’s grant from Polaroid was arranged by the Aperture Foundation and gave her access to one of the only 20×24-inch Polaroid cameras in the world at that time. Fittingly, the camera was originally intended for medical research; in Simpson’s hands, it became a tool for creating 25 unique photographic prints that invoked the horrific loss of life due to HIV/AIDS in 1992—a year in which the virus was the leading cause of death for men between the ages of 25 and 44.

Note: This artwork is on view starting February 14, 2026.

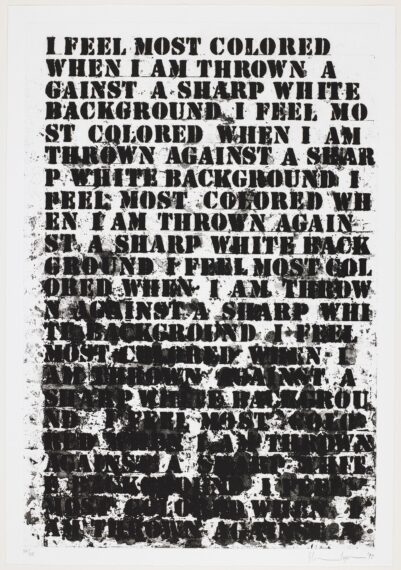

Glenn Ligon: Untitled: Four Etchings (A), 1992 (Gallery 375)

Glenn Ligon, American, born 1960. Untitled: Four Etchings (A), 1992. Greg Burnet, New York, Printer; Max Protetch Gallery, New York, Publisher. Soft-ground etching, aquatint, spitbite, and sugarlift etching. Gift of the Print and Drawing Council. P.93.17.1. © Glenn Ligon

Glenn Ligon draws on African American cultural and social history to create politically charged work that connects past and present. In this untitled portfolio of etchings, he explores the persistence of racism by appropriating texts from two major Black writers. The prints with black text on white paper feature excerpts from Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay How It Feels to Be Colored Me, which Ligon uses to reflect on the idea of “becoming colored” and the ways identity can be obscured or abstracted. The prints with black text on black paper include a passage from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), describing Black Americans as unseen despite their presence. Together, these four prints symbolically evoke ongoing racial divisions in the United States.

Note: This artwork is on view starting February 14, 2026.

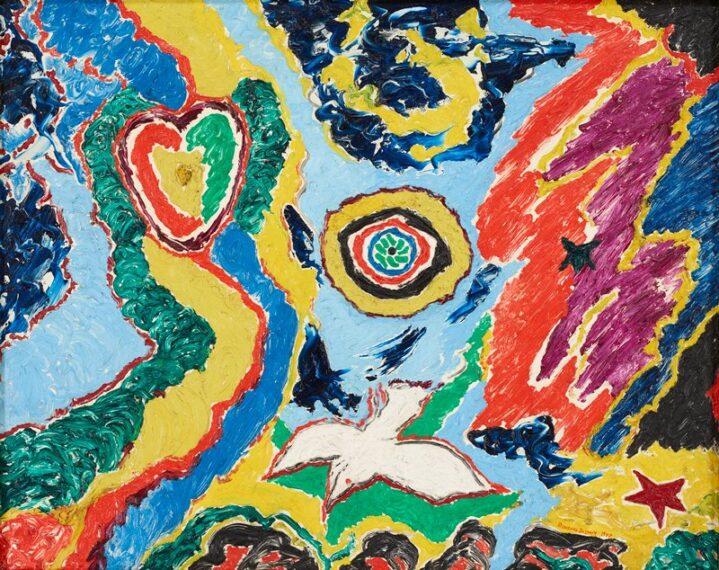

Beauford Delaney: Untitled, 1947 (Gallery 376)

Beauford Delaney (1901–1979), Untitled, 1947, oil on masonite. Gift of Dolly J. Fiterman, 2017.138.7. © Estate of Beauford Delaney / Derek L. Spratley, Esq., Court Appointed Administrator

Beauford Delaney attended art school in Boston and then moved to New York in 1929. A lover of jazz and blues music, literature, and the theater, Delaney befriended and painted many writers, actors, and musicians. He lived in Greenwich Village and was inspired by the lively streets and diverse community. His paintings expressed the excitement of city life in vivid colors, energetic lines, and quick brushstrokes. As a gay African American man, he faced discrimination in the United States; Paris was more tolerant. Delaney left New York for Paris in 1953, and he spent the rest of his life working there, moving from figurative to abstract painting.

Note: This artwork is on view until February 14, 2026.