Art in the Age of Globalization

September 16, 2012 - July 14, 2013

Target Wing

Free Exhibition

Spanning centuries and originating in nearly every place on Earth, the artworks in these galleries explore significant aspects of the world’s evolving cultures. “Art in the Age of Globalization” presents eight installations, or “mini-exhibitions,” each designed around a specific narrative or theme related to globalization.

In this area of the museum, curators have mined the MIA’s collection to create a series of installations that explore various elements of globalization as they have developed across time and cultures. The exhibitions are:

“The Digital Age”

Donna and Cargill MacMillan Atrium (third floor)

“Faith in Motion”

Robert and Marlyss White Gallery (281)

“Global Fusion, or, It’s a Flat World, After All”

Gallery 276

“Global Migrations and the Landscape”

Galleries 277, 278, 279

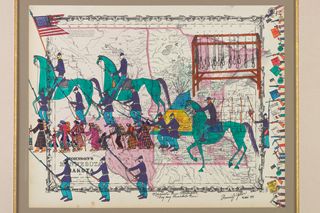

Left: Francis J. Yellow, Lakota (Sioux), Great Plains region, born 1954, Minnesota Nice Oyakepelo, “They Say Minnesota Nice,” 1995, acrylic on paper. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

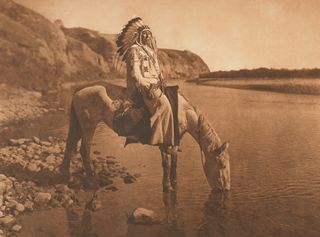

Right: Edward Curtis, American, 1868-1952, Bow River – Blackfoot, 1926, photogravure. Gift of Joe Langer.

This installation explores the effects of globalization from a variety of perspectives, including that of people displaced from their homelands and historic cultures undergoing erosion. The indigenous people of what is now North America were displaced from their birthplaces by European settlers, who tried to extinguish the various Native cultures they encountered. Contemporary artist Francis Yellow uses traditional ledgerbook imagery to recount the devastating story of the war between the Dakota people and the U.S. Government in 1862. In contrast, Edward Curtis photographed Native Americans in staged, idealized compositions that glamorized their true plight and history.

“Outsourced”

Linda and Lawrence Perlman Gallery (262)

“Porcelain as a Global Commodity”

StarTribune Atrium (Gallery 180)

Left: Johann Joachim Kändler, German, 1706-75, America, c. 1745, hard-paste porcelain. Meissen Porcelain Factory, manufacturer. Gift of Leo A. and Doris Hodroff.

Right: Peter Behrens, German, 1868-1940, Soup Plate, 1901, porcelain. Porzellanfabrik Gebrüder Bauscher, Weiden, Germany, est. 1881, manufacturer. The Modernism Collection, gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota.

Crafted, possessed, treasured, imitated, marketed, shipped, sold, coveted–these words could be used to describe global commodities such as gold and silver, but in fact, cover the trajectory of porcelain, a material valued and traded in world cultures for centuries. Through examples from the MIA’s collection and loans, this exhibition tells of porcelain’s rise as a global commodity, along with its changing uses and meanings.

International trade organizations such as the Dutch East India Company meant Chinese porcelain was reaching markets in Southeast Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. Europeans began to chase the holy grail of true porcelain. It led to the establishment of global European centers of porcelain in Meissen and at Sèvres. America is an interpretation of its namesake in the form of a Native woman surrounded by indigenous animals, all thought to be “exotic.” The Behrens plate shows how the Industrial Revolution allowed porcelain to be a vehicle for modernism for middle-class consumers in the early 20th century.

“Regeneration”

Gallery 275

Left: John Chamberlain, American, 1927-2011, Whitmore Wash, 1969, painted chromium steel. Collection of Gordon Locksley and George T. Shea.

Right: Yuji Honbori, Japanese, born 1958, Eleven-headed Kannon, 2012, cardboard, wood, plastic, pigments. The Joan and Gary Capen Endowment for Art Acquisition.

All of the artworks in “Regeneration” are made from cast-off goods, recycled paper and cardboard, and other disposables. Here, artists reflect the creative ability to make beauty out of the trash that is a by-product of global consumerism. Chamberlain’s Whitmore Wash is made from a crushed washing machine. In Honbori’s Eleven-headed Kannon, the gossamer quality of corrugated cardboard suggests notions of impermanence and ephemera in this stunning sculpture, which is based on a famous eighth-century temple Buddha from Nara, Japan.

“A Drop to Drink”

US Bank Atrium (Gallery 280)

Left: Yang Shou, China, Storage Jar, c. 2,400 BCE, earthenware with painted decor. The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund.

Right: Lobi, Burkina Faso, Jar with Lid, 20th century, ceramic. Anonymous gift of funds.

In one installation, titled “A Drop to Drink,” objects made over a period of thousands of years and representing cultures from around the globe tell the story of water, in terms of its beauty and fury, its abundance and scarcity, and its power and transport. The aesthetics and technology of these two water carriers – made thousands of years apart – has changed little over the centuries.

At the heart of each of these displays lie the beauty, history, and power of objects–as they connect history with critical issues of our times.