By Tim Gihring

Erika Lee’s grandfather came to the United States from China in 1918, sailing into the harbor of San Francisco. He was 16, a farmer’s son. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which was designed to stop nearly all Chinese immigrants from entering the country, had been in place for 36 years. But he had paid a thousand dollars for papers from a merchant, one of the few classes of Chinese immigrants allowed in, a man who had agreed to claim him as a son.

Lee’s grandfather memorized his new identity: new name, new family history, everything. After a couple of weeks off shore, in detention on Angel Island, including medical exams and 145 questions about his paper family back home, he stepped onto American soil as a new man in a new country.

Lee grew up knowing few of these details. It wasn’t until college that she learned of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was strengthened in 1924 to preclude all Chinese immigration before being repealed in 1943, against the backdrop of World War II. (China had become an ally against Japan, and the tide of American xenophobia turned toward Japanese Americans instead.)

The subject had just never come up, at home or school. “The standard narratives about American history left a lot of people out,” she says of her education in the 1970s and ’80s. “That’s not surprising, in many ways, and we’ve done a much better job since of telling the darker chapters of history.”

Lee is now one of those historians. A distinguished professor at the University of Minnesota, she’s the director of its Immigration History Research Center and the author of several books on the history of immigration, including The Making of Asian America: A History and, most recently, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States. She served as an advisor to Mia on bringing the current exhibition “When Home Won’t Let You Stay: Art and Migration” from the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, and reconstituting it in the Twin Cities with the perspectives of the area’s distinct immigrant communities.

A Chinese New Year Celebration in San Francisco, in 1953, photographed by Zoe Lowenthal. From the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

She grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, and says her family—like the history books—didn’t delve too deeply into what, for them, was historical trauma. “They were so focused on proving that they were—and could be—true Americans that they did not want to dwell on the past and bring up these pretty traumatic memories,” she says. “They wanted to send their children and grandchildren forward to achieve whatever that American dream might be that had sent them from China in the first place.”

In her latest book, she has expanded her focus to the xenophobia that has countered nearly all immigration at almost every turn in the history of the United States, going back to Benjamin Franklin opposing an influx of Germans in the 1750s. To understand this history, in which the same arguments are used against one group of people after another (they’ll never respect our ways, they’ll take our jobs, there’s too many of them) is to understand something about “Americanness.” Indeed, as each group of immigrants succeeds in becoming more “American,” they take on some version of this dark and persistent characteristic.

“History is built on precedent,” Lee says. “So when we’ve treated one group unfairly, it’s easy to extend that worldview to another group. Sometimes those who’ve recently been excluded have turned around and found another group to marshal Americans’ attention towards, unfortunately. It’s a way of expressing one’s Americanness to be exclusionary and to point to foreigners as dangerous.”

The Melting Pot Paradox

Lee used to explain American xenophobia to her university students more or less the ways historians have long thought about it, that sometimes we’ve been more accepting of immigrants and sometimes we have not. Or that we’ve evolved, learned our lesson, never to fully return to the xenophobia of the past. But around 2015, in the run-up to the presidential election, Lee concluded that wasn’t really accurate.

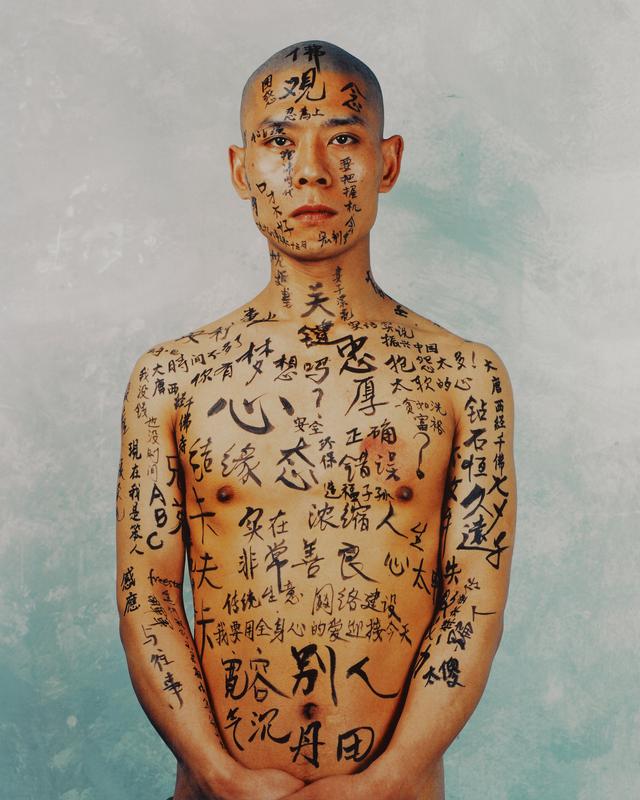

“1/2 (Text)” is a self-portrait by Zhang Huan, who invited friends to write phrases on his body before leaving China for the United States. From the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. © Zhang Huan Studio, courtesy The Pace Gallery

“I realized that after two terms of our first African American president and 50 years after the Civil Rights Movement, this was still happening,” she says. “And in even more cruel and explicitly racist ways than we had thought were long over.”

And yet, as barriers to immigration have gone up once again in the United States, there has also been an outpouring of support, from marches against the Muslim ban to yard signs celebrating diversity—a contradiction that is now at the heart of Lee’s research.

“Through the historical record, I realized it’s not one or the other,” she says. “It’s not ebbing and swelling, or rising and stopping, it’s happening simultaneously.”

How people perceive immigration, she says, may ultimately depend on how it is framed. Do we think of it as a legal question, framed around the divisive issue of illegal border crossings? Or do we think of it as a question of motivation, a universal truth of human need?

Understanding the culture of immigrants—seeing people the way they see themselves, in their art, their food, their music, their poetry—can move the conversation into that universal space. Our art and culture reflect our values, our motivations, our roots—the things we’re attached to. The things that comprise our home. To a historian like Lee, looking at myriad streams of migration over millennia, one simple thing binds them all together: no one leaves home unless they have to.

“It’s not that people are waking up one day and saying, I’m going to leave everything that’s familiar, my family and friends, because I want to break into the United States,” she says. “Laws be damned, I want to take something from those Americans. Migrants are rooted in our home—we’re human. But when something happens that makes it necessary to leave—when home won’t let you stay—then people will go to any lengths to seek refuge. They have throughout history.”