Eugène Delacroix’s 1829 lithograph of a lion munching a rabbit looks like a stuffed animal next to the animated creatures he painted some 30 years later in Lion Hunt (1861), the signature image of “Delacroix’s Influence: The Rise of Modern Art from Cézanne to van Gogh” (on view in Mia’s Target Galleries, now through January 10, 2016).

Delacroix knew the two animals in Lion of the Atlas Mountains (1829) from dissections.

What changed? Delacroix came to believe that lions and tigers, which captivated 19th-century Romantic artists, were more than symbols of exotic adventure and uncontrolled power. Lions in particular, he decided, shared anatomical traits with humans, and he gradually expressed this notion in his paintings and prints.

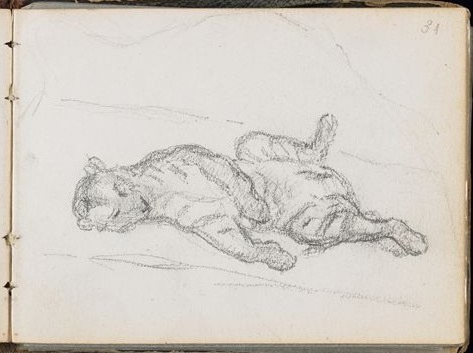

Delacroix’s feline fascination was fed by visits to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, where he had permission to draw the zoo animals. Mia’s pocket sketchbook from the French sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye (1796-1875), who accompanied his friend on these outings, shows the wonderful spontaneity of their life studies.

Of Delacroix’s nearly 60 tiger prints, Royal Tiger (1829) is perhaps his most renowned.

Two of Delacroix’s most celebrated prints owe their striking realism in part to those sketching trips: Lion of the Atlas Mountains (detail above), and its pendant, Royal Tiger, both from 1829 and both in Mia’s Department of Prints and Drawings. They alone are worth a trip to the Print Study Room. Each animal also reflects the vogue in 1820s France for finding outward correspondences between animals and humans—as in the Atlas lion’s nonchalant demeanor and the tiger’s pretending as if he couldn’t summon his bulk into a deadly pounce.

Around the time he was completing these masterpieces, Delacroix leaped at the chance to draw a flayed lion, a rare opportunity in 19th-century France. He had already done dissections, including a hare at around age 20. But art historian Eve Twose Kliman reports that seeing the flayed cadaver impressed upon the artist the similarities between human and lion limbs.

Lioness Clawing an Arab’s Chest (1849) was Delacroix’s final etching.

Gradually, Delacroix’s felines started taking on certain human characteristics. In Mia’s lithograph Lioness Clawing an Arab’s Chest (1849), for example, the lion’s muscular foreleg and bent elbow resemble a man’s. Kliman says Delacroix may have intended the lion’s sharp elbow in Mia’s Lion Devouring a Horse (1844) to look human, too.

The lithograph Lion Devouring a Horse (1844) demonstrates the ferocity and untamed spirit the Romantics loved.

By the time he painted Lion Hunt, Delacroix was exploring these affinities at full bore: The hand grasping the foreground lion’s mane looks like the paw below it, the side-by-side knees echo each other perfectly, and the lion’s right wrist affects a very human bend. There are subtler parallels, too, like the way the lioness’s tail curves into the billowing white cape of the swordsman behind her.

Antoine-Louis Barye sketched animals with Delacroix at a Paris menagerie. Barye’s sketchbook in Mia’s collection shows their cooperative subjects.

In 1861, the year Delacroix finished Lion Hunt, it appears he wanted fervently to believe that humans shared not just their limb structure with lions, but their energy as well. Art historians believe that he gained strength from simply painting these beasts. That year he wrote in his journal: “Now nothing charms me save painting and now, into the bargain, it gives me the health of a man thirty years old.” Frail nonetheless, he died two years later, at age 65.