By Diane Richard

For years, Mia had a booth in the cavernous Education Building at the Minnesota State Fair, giving away things like cardboard fans, dubbed “Art on a Stick.” With the flick of a wrist, the eye-catching freebies kept fairgoers cool during those sticky hours at the Great Minnesota Get-Together, which of course is on ice this year for pandemic prevention efforts.

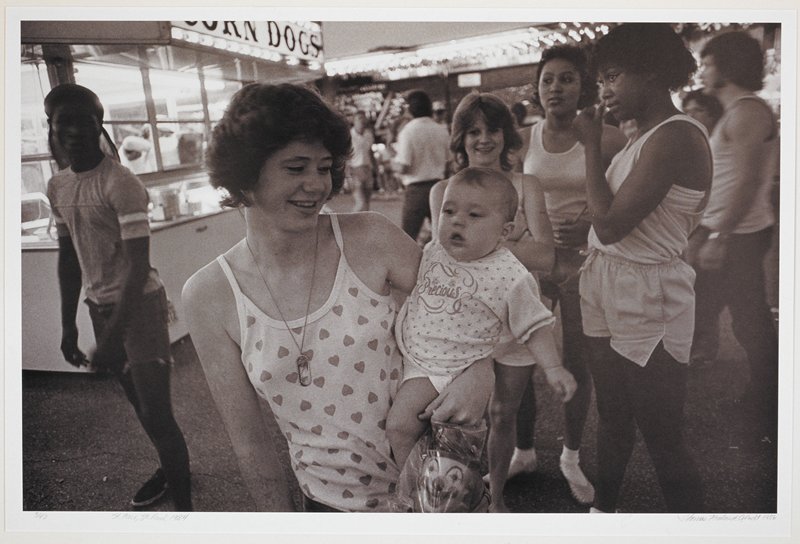

“Zipper, Midway, Minnesota State Fair,” by James May, 1982. Color coupler print. Collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. © James May

Sixteen years ago, the fans were printed with seed-art portraits by Lillian Colton, a Minnesota State Fair legend. With tweezers and painstaking attention to detail, the Owatonna artist immortalized celebrities in sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, poppy seeds, wild rice, and tiny specks of bird food—everyone from Barbra Streisand to Eleanor Roosevelt, Garrison Keillor to Willie Nelson, and a mesmeric Prince.

That summer of 2004 was a big one for Colton, who was then 93. Some of her works simultaneously hung at Mia, right off the lobby, in a show called “Lillian’s Vision.” It was curated through the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program (MAEP) by Jan Elftman, whose populist art also features tiny materials—usually glued to cars.

Colton died three years later, but Mia’s overlap with the Minnesota State Fair goes well beyond seeds. Indeed, the line between Fair Oaks and the fairgrounds is brighter than a free DayGlo yardstick.

Total Rando

Corpulent sows! Caramelcorn vendors! Dazzling neon rides on the Midway! For subject matter, one cannot ask for a more robust visual feast than the Minnesota State Fair. Photographers in Mia’s collection, such as Tom Arndt, Jerome Liebling, Stuart D. Klipper, and James May, all took obvious delight. Search any of their names on artsmia.org/explore, and you can almost smell the grease and humanity.

“Hotsy Totsy” by Clement Haupers, 1928. Soft-ground etching. Collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Mia’s collection also includes work by Clement Haupers, a St. Paul-born artist who in 1931 became the superintendent of the Fine Arts Department at the fair. Haupers had lived a bohemian artist’s life in Paris, and his art at Mia reflects his cosmopolitan outlook, from regional landscapes to etchings of raucous, feathered fun at the Folies Bergère. But he defied the fair’s custom of promoting art from New York and Chicago galleries, instead using his role to lift up Minnesota art and artists.

One exception: In 1954, the Fine Arts display made an impression when “The Institute” joined the Walker Art Center in contributing pieces to the fair, including two Matisses and a Renoir.

With Haupers came juried prize shows. Sam Sachs II, who led the museum from 1973 to 1985, served as a juror for the Fine Arts show, and many Mia staffers have shown art at the fair.

Tim Piotrowski, a security guard at Mia for 39 years, has honed his photography technique through interactions with a succession of Mia’s photography curators. Entering his vintage-seeming photographs in the Fine Arts competition, he said, puts his work in good company.

“Everybody enters the fair,” he says. “It’s not some kinda Podunk deal.”

For every acceptance, of course, there are rejections. In local art circles, “It’s the State Fair” has become shorthand for inscrutable judging.

“It’s become the pinnacle of the unpredictable juried show,” Piotrowski says. “It’s total rando.”

Show, Place, or Win

Photographer Steven Lang, who works in Mia’s media and technology department, guesses he has submitted work 25 times and been spurned 15.

“Getting rejected is a ritual,” he says.

Lang enters the competition for the colossal audience it draws. “It’s a Minnesota thing to do,” he said. “I run into people all the time who say, ‘I saw this at the State Fair.’ I mean, 100,000 people will see your stuff.”

Alec Soth, a former staff photographer at Mia, produces artwork that is widely acclaimed, collected, and published as a member of the esteemed Magnum Photos group. (A 2015 series that appeared in The New Yorker consisted of photographic portraits of Mia security guards and their in-gallery musings.)

Soth has entered his photography in the fair several times. He won a blue ribbon for an image of a clown and a cop, sitting in the same cafe. Yet even titans trip. In 2012, Soth blogged his rejection note from the fair, which said, “We regret to inform you that your piece titled Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, entered in Class 8 – Photography/Digital Process was not selected to move on to Phase 2 of the jury process. … Thank you for your participation!”

It’s the exclamation point that hurts.

Things are a bit looser in the Creative Activities Building. Every item that’s submitted enters the competition. Ken Krenz, associate registrar for Mia’s permanent collection, has won ribbons for his Irish Aran cabled cardigan and a scarf of his own design (called the Tire Scarf for its distinctive textured tread).

Krenz enters for the glory—which sometimes comes with a jab.

“When you pick up your piece after the fair, you get your scorecard with the judges’ comments,” he says. “I’ve had some [comments] that were like ‘Your socks are beautifully done, but the winning socks were more technically difficult.’ But they also could be snarky: ‘Why would you want to knit this pattern with this yarn?’ Some things they’ve pointed out have actually improved my knitting. Other times, I’m like, ‘Keep your opinions to yourself, lady!’”

So Much Emotion

Also in the Creative Activities Building is the Culinary Arts competition. That’s where Frances Lloyd-Baynes applies her skills in data documentation at Mia as an intake clerk at the fair. She got hooked while working at the American Swedish Institute with its curator, Curt Pederson, who has ridden herd over Creative Activities for 44 years.

Clerks are responsible for the paper trail. They track each entry, all 6,000 of them, with fusty old-school paperwork—in triplicate. “Horrendous bits of paper!” says Lloyd-Baynes.

“It does drive me nuts we don’t have a barcode reader,” she says. “When I see that carbon paper, I say, ‘Oh god, not again.’”

Lloyd-Baynes spent her first year in the Canning and Baking competition, documenting entries and preparing samples for judging.

“One of the worst things I had to do was the vegan main dish entry,” she said. “You have to plate it, heat it, get it ready for the judge to taste. It was so elaborate and involved. I decided it was not my thing. I moved to Cakes and Pies.”

To hear Lloyd-Baynes tell it, the work is as exhausting as, well, a day at the fair.

“Cakes have to be delivered in a box,” she says. “You have to unbox them without putting your finger in the frosting, which is challenging. Then you have to cut a slice of every cake the judge wants to taste on each plate.”

Multiply that by angel food cakes and devil’s food cakes and Bundt cakes, etc., and then move on to pies and jams. Spooning jams for judges to sample is part of a clerk’s job. “You don’t want your blackberry jams in with your strawberry jams,” she says.

After nine years as a clerk, Lloyd-Baynes will miss this year’s Covid-19–curtailed shifts at the fair. As at Mia, she says, “There is so much emotion embedded in these objects that are put into our care.”

Craving a Taste of State Fair Creativity?

The Fine Arts competition at the fair is happening. You can get timed tickets to visit the Fine Arts building in person, August 27–September 7.

Consider entering “Foot in the Door 5,” the once-a-decade opportunity for all Minnesota artists to show their work at Mia—this year virtually. Digital submissions will be accepted September 8–28, 2020.