By Casey Riley and Tim Gihring

Meadow Muska was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1952, and grew up in the nearby suburb of Roseville. She earned a degree in photography from Ohio University and eventually got a job as a staff photojournalist with a small-town newspaper in Oregon. It didn’t last long. She was fired, she believes, because someone learned that she’s a lesbian.

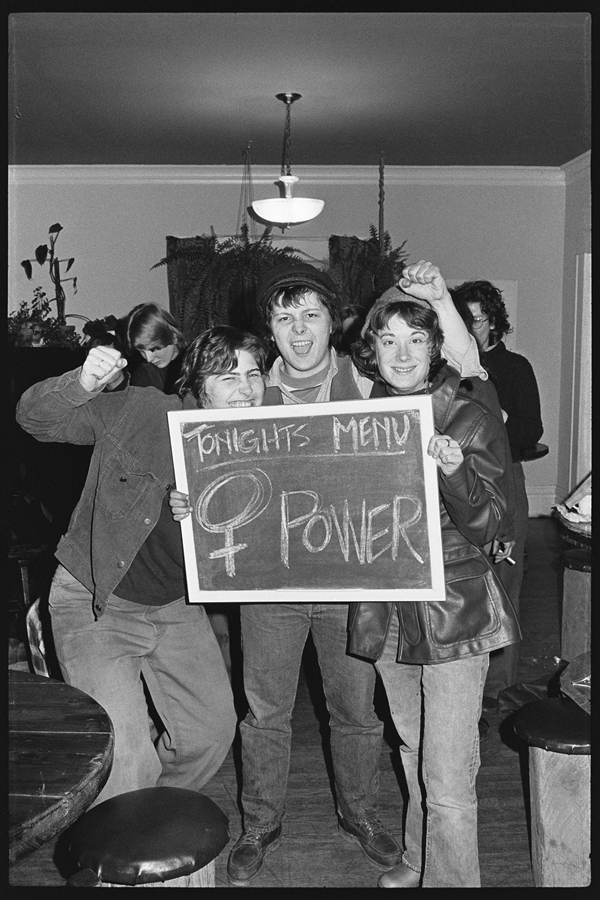

Muska never found work in journalism again. In fact, for years she photographed in relative secrecy, living in a van she rebuilt herself and, later, printing her film in a basement darkroom. But her images of lesbian life, particularly the women’s land movement (communes where women found strength and refuge in the woods), have become a valuable document of love and survival amid violent repression. Earlier this year, her archive of images entered an important collection of women’s history at Smith College, and now 30 of her photographs are being shown at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in “Strong Women, Full of Love,” the first exhibition of her work.

Casey Riley, the show’s curator and head of the Department of Photography and New Media at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, talked to Muska about her life and work, and what spurred her to bring these images to light.

Riley: After college, you lived near the museum. Tell me about your history with the neighborhood.Muska: Yes, this was around 1974, before I went to New Mexico and Oregon. I got an apartment lent or passed on to me for sixty dollars a month. The conditions were that I paid the rent and other people had keys and they got to stay there, too, whenever they needed. And that’s where I built my truck, the step van that I got from the Minneapolis postal auction: a 225 Slant Six one-ton step van. I built it into a safe vehicle so that I could travel and live safely. I added paneling, cupboards, carpet, and a piece of foam as a bed to the rear of the truck. It had a locked, caged door, so I was dry and safe and had everything I needed.

After losing your job with the newspaper in Oregon you went into the trades. A world that was not easy for you to inhabit, and you did a lot of work to make it safer for women and people of color. What was that like?

Nobody would hire me as a photographer. The only opportunity I was even able to apply for was to be a portrait photographer at Penney’s, where you take squeaky toys and play with kids. I said, I can’t do that. So I had to re-train. My father was in construction, he was an electrical contractor, and he said, “If you study to be an electrician I will pay for it.” So I was the first woman to make it through two years at Dunwoody [College of Technology]. It was horrific. The men picked on me repeatedly, they changed wires on my stuff. It was an unbelievably abusive situation. But I graduated—second in my class, I think — and I went to work at IBM.

Your life outside of work became your lifeline. How would you describe the women’s land movement, creating these places of safety and survival?

It was a safe place to feel human. At Dunwoody, or even in public, it wasn’t safe. We could be at Rising Moon [a women’s community near Aitkin, Minnesota] or Cabbage Lane [in Oregon] on some land and feel like we could just be human beings, without fear of being attacked.

In 1974, I went into the lands — I think it was Cabbage Lane — and a one-ton pickup truck got stuck in the mud while the women were trying to garden or build little shacks to live in. There were maybe eight of us. We just looked at each other, like, well it’s stuck — nobody was going to come help us. How do you push this thing out? But we were all strong and pretty bright, and the next thing you know we had wood under the tires and were pushing and pulling that truck onto the road. Someone said, “Boys do it, how hard could it be?” It was very empowering to realize that from society’s viewpoint we were nothing, but on our own we were able to do whatever we chose to do. We just had to work harder at it and figure it out on our own.

Building trust was an important part of our process of working together. You were very worried at times about putting your photography out there. Can you talk about the emotions and intentions around your work?

The reason I photographed was to be a conduit, to show who we really were as human beings and not how we were seen — which was as perverts, literally. Sexual deviants. That’s what I grew up with. We would lose our jobs, our careers, and face violence because of this. I have seen the results of my friends beaten and raped, a reality that is not some fiction on a TV show or in a movie or book. For me, it’s “Diana got beaten.”

I don’t believe in denial or apathy. I believe that witnessing the truth is far more important than entitled people’s sitcom view of reality. We have to put the facts on the table and deal with that.

For a long time, you were concerned that your work might get someone in trouble — including yourself. Then, in 2014, you saw a photography show in Belgium.

Yes, this show of rock stars in the 1970s. The way this guy portrayed women then as groupies, willing to be in sexually derogatory positions — that was not my reality. I don’t want women now or in the future to think that’s who all women were in the ’70s. We built a different reality and I need our reality to be shown equally. We were and have always been a very noble and strong group of women.

As a curator, it’s been really important to signal to women that I am here to see their work. And here you are. But you were really persistent and resilient in finding a place to show your work—it wasn’t easy.

Nobody believed I had photographs of value, even though people had taken them and stolen them and donated them to books and TV programs and archives — without crediting me. They were highly valued for that. But I would call up printers and say I’d like to talk about printing my work, and they wouldn’t even return my calls. I’d call copyright lawyers and they’d pooh-pooh me: you don’t have any need for copyright, you’re some hobbyist old lady. I believed my work was significant — it meant a lot to me — but it was very painful to try to convince others.

Who do you hope to reach with your photography now, and what do you hope they take from it?

I’d like to reach out to somebody who doesn’t politically or religiously feel comfortable with women who bond with other women. So you can look at our faces and see we’re just like you and your daughters and your sisters and your mothers — we’re just like you.

I want to connect with younger people, too — people of conscience — so we can build a better, more just world and keep it alive. Us older people have the experience and the networks, we’ve been doing it all our lives. Here’s the baton, pick it up.

Top image: Meadow Muska’s photograph “Tradeswomen: Get Serious!” from 1976.