By Lori Williamson //

Is it cliché to celebrate anniversaries? When I was younger, I wouldn’t celebrate my parents’ anniversary, insisting that since I wasn’t there for the beginning, it didn’t have anything to do with me.

Now that I am wiser (older), I realize I should thank my lucky stars every day that they found each other. I usually get them a plant.

As the co-curator of the exhibition “Gatsby at 100,” I’m sure you’re likely unsurprised to hear that I now relish anniversaries, my own and others. Anniversaries offer an excellent opportunity to pause and carefully reflect on something—whether it be a work of art, a relationship, or simply the passage of time. They allow for consideration of both the thing itself and its impact on the world.

Carefully Considering Albrecht Dürer

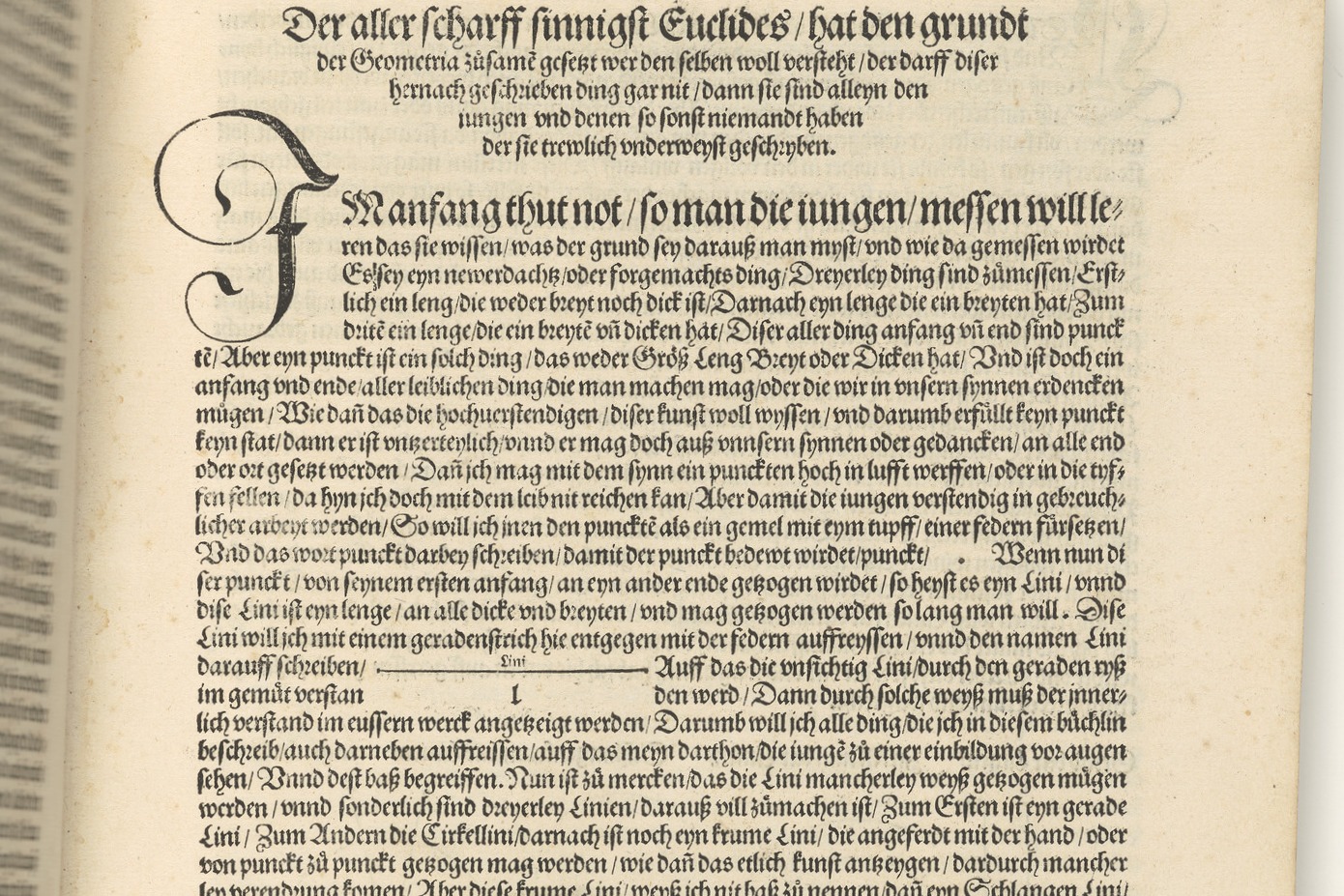

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528), Underweysung der Messung, 1525, book in original vellum binding. The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books, 2024.47

With this in mind, I am thrilled to share Instructions in Measurement, a book by Albrecht Dürer.

Or perhaps the more complete title would be helpful, which may be translated as “Lessons in measurement, with the compass and ruler, into lines and whole bodies, drawn together by Albrecht Dürer, and for the benefit of all art lovers, with the corresponding figures, brought into print, in the year 1525.”

This book entered Mia’s collection last year, but was published 500 years ago in 1525. It’s complete in its original binding. From what we can tell, it was likely purchased in Nuremberg by a German noble family and kept in their library. Mia is likely only the second owner. Clearly, this book was used and studied. While it’s in good shape, the pages have seen some wear, and there’s marginalia noting essential passages.

Dürer: More Than Meets the Eye

A 500-year-old book is cool, obviously, but it’s so much more than that. Dürer was a renowned artist who excelled at both painting and printmaking. A true Renaissance man, Dürer visited Italy and learned how to use proportion and perspective in his art by studying ancient classical sculptures such as the Apollo Belvedere and the works of artists like Verrocchio and di Credi, possibly exchanging art and admiration with Raphael.

It’s been said that when Dürer returned to Germany, he brought the Renaissance north with him. Dürer, being the intellectually curious person he was, also learned a great deal from careful study of the rich library belonging to Willibald Pirckheimer, one of his dearest friends and a prominent figure in Nuremberg.

Albrecht Dürer grew up in Nuremberg, a wealthy, independent trading hub in Germany. His father was a goldsmith. From a young age, Dürer learned to draw and use tools to manipulate metal. Rather than follow his father’s path, he became an apprentice to Michael Wolgemut, the leading artist in town. Dürer would spend the rest of life making paintings and prints. While supremely gifted in both, toward the end he said he wished he’d focused on printmaking.

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528), Underweysung der Messung, 1525, book in original vellum binding. The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books, 2024.47

Knowing he wouldn’t live forever, Dürer planned to write four books to share what he’d learned with future generations. He died in 1528 before he could write his book on how to draw the perfect horse, a subject he cared about greatly, given the impact a horse could make on the reality of a piece. (I also highly recommend comparing a Dürer horse to those that came before—his are glorious!) In 1527, he published Various Lessons on the Fortification of Cities, an obscure topic, perhaps, but one that also used geometry.

Dürer’s Impact

Dürer’s most important and impactful books were his Lessons in Measurement (1525) and On Human Proportions (1528).

Full disclosure: while I read the English translation, I love everything about the original book. I love how it looks and smells, and how the excellent rag paper sounds as one turns the pages.

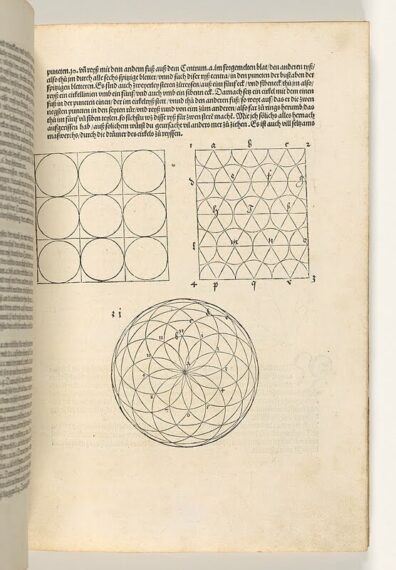

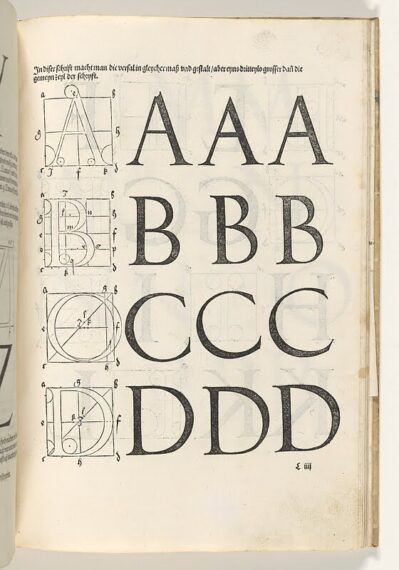

I love the beautiful woodcut illustrations made by Dürer, which demonstrate his points.

I love the care Dürer took in writing the book, patiently walking readers through each lesson, consistently demonstrating why each one is important, how each builds off what came before, and often where he originally gleaned this knowledge.

The book starts with a simple declarative sentence of intent: “The most sagacious of men, Euclid, has assembled the foundation of geometry. Those who understand him well can dispense with what follows here, because it is written for the young and for those who lack a devoted instructor.”

Dürer goes on to say that this book is for artists, architects, goldsmiths, sculptors, stonemasons, carpenters, and anyone else who needs to understand measurement. It begins by measuring lines, dividing them, and increasing their length.

The book then proceeds to consider area, angles, and volume, ultimately concluding with polyhedral solids (a three-dimensional object with multiple faces). The importance and uses of geometry are on full display.

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528), Underweysung der Messung, 1525, book in original vellum binding. The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books, 2024.47

But That’s Not All!

Dürer also offers us such pro tips as: when creating a memorial column, ensure that it accurately represents the group or event it commemorates. And if one is going to bother putting words on a building, make sure they are sized appropriately so they can be read, taking angles and height into account.

Need to know how to make a sundial? Directions and images can be found here. Or how to make the perfect Latin or Fraktur (German) type? Yes, those instructions are also included in this volume.

There are even foldouts from 500 years ago demonstrating proper perspective!

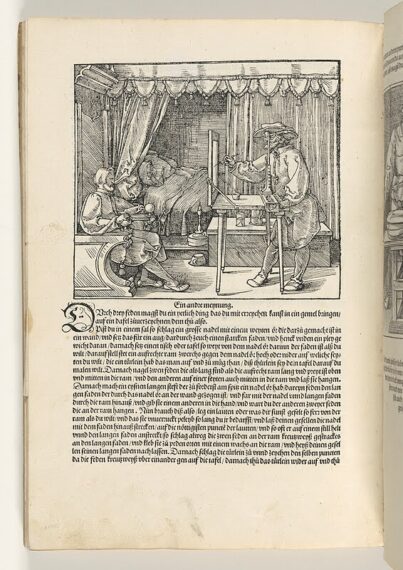

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528), Underweysung der Messung, 1525, book in original vellum binding. The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books, 2024.47

The most well-known images from the book are on the last two pages. Illustrated here are two inventions that Dürer describes as examples of how to achieve perfect perspective. The first shows a portrait being created, with the artist using a rest for the chin and a frame that holds translucent paper. The chin rest is designed to keep the artist’s perspective steady as they behold the subject.

The second device is even more elaborate and takes two people to use: one who points to a spot on the subject (in this case, a lute) with a marker attached to a weight. The second, who notes where the marker crosses the plane when it is released by the first and the weight pulls it. It will be the most perfect lute imaginable using this technique.

One of the most remarkable aspects of this incredible 500-year-old book is that it serves as a physical reminder that art and science are not contrary or separate disciplines. Rather, they work together to help us understand and share ideas about the world and ourselves within it.

Mia’s Print Study Room has a growing collection of books on drawing, artmaking, and the science underlying these disciplines. These books also prove to be works of art in their own right.

About Lori Williamson, Supervisor of the Herschel V. Jones Print Study Room at Mia

Lori Williamson creates mini-exhibitions and teaches classes and Print Study Room visitors about the museum’s rich collection of works on paper. She’s the primary caretaker for more than 40,000 prints, 6,000 drawings, and 600 artists’ books, collaborating with curators in American, European, and Global Contemporary Art to make these holdings accessible. Williamson supports scholars through research and inquiry, and advocates for the inclusion of works on paper in exhibitions, social media, and outreach, helping to connect diverse audiences with this dynamic collection.

Lori Williamson creates mini-exhibitions and teaches classes and Print Study Room visitors about the museum’s rich collection of works on paper. She’s the primary caretaker for more than 40,000 prints, 6,000 drawings, and 600 artists’ books, collaborating with curators in American, European, and Global Contemporary Art to make these holdings accessible. Williamson supports scholars through research and inquiry, and advocates for the inclusion of works on paper in exhibitions, social media, and outreach, helping to connect diverse audiences with this dynamic collection.

Interested in seeing something in the Print Study Room? All are welcome by appointment. Email Lori Williamson and copy the Print Study Room to make an appointment.

Meet the other curators in the Department of European Art.