At the end of 2016, China extended a potential lifeline to elephants, rhinos, and other ivory-bearing animals. China has vowed to shut down its country’s commercial trade in ivory by the end of this year, closing the world’s largest market for tusks, horns, and other ivory material. If the ban is effective, it could dent the alarming rise in wildlife poaching that has stirred predictions of imminent elephant and rhinoceros extinctions.

Mia has many ivory pieces in its collection (none of them made recently). As their stories demonstrate, China’s move is just the latest in a deadly business that goes back centuries, a global obsession with so-called “white gold” that has been a powerful force in politics, war, slavery, and art.

Big tusks

A carved elephant tusk commissioned by a military commander in Benin in the late 1700s. On view in gallery G250.

As elephants and rhinos near extinction, their ivory has only become more valuable—there is even evidence that criminal gangs are now hastily slaughtering the remaining animals and stockpiling their horns and tusks for the day when there is literally no more supply to meet demand.

But this is just the pathetic end of a very long story. There were once elephants in North Africa; ivory hunters wiped out that population perhaps a thousand years ago. Ditto for much of South Africa in the 19th century, and most of West Africa in the 20th century. We are now largely down to East Africa, where shrinking habitat and the killing of large bulls means the days of elephants bearing tusks as large as the one from Benin on display in gallery G250 are almost certainly over.

White noise

A grogger is used as a noisemaker during the Jewish holiday of Purim, grogger being Yiddish for rattle. In medieval times, its noise was thought to evoke the grinding of Judas’ bones.

During both world wars, the use of a whistle to alert citizens of an impending chemical bomb attack was impossible—gas masks got in the way. Instead, military forces twirled groggers as alarms. Today, the devices are more widely recognized as a tin toy brought out for New Year’s Eve celebrations. Why Mia’s grogger, on view in gallery G362, is made from ivory is anybody’s guess. Could be that the artist saw a parallel between grinding bones and carving tusks.

The banal and the beautiful

Over the centuries, elephants and rhinos have been slaughtered so their tusks and horns could be carved into objects both ceremonial and simple: royal bling and billiard balls, cruxifixes and piano keys. (If you have a halfway decent piano made before 1970, you’re likely tickling the ivories, as they say.) The chess set displayed in Mia’s Charleston Drawing Room, made in China in the 1700s, shows what a creative carver was capable of, in the fine filigree and detail.

Recently, the chess business has moved on to even more exotic, if already dead, sources. You can now purchase ivory chess sets made from 40,000-year-old mammoth tusks. Rather ordinary looking. But considering the rarity, the $8,500 price seems almost prehistoric.

Carving ivory

The majority of tusks taken from killed elephants today are turned into trinkets that would never find their way into museums, even if they could. But in the past, master sculptors were drawn to ivory for its malleability, which allowed skilled carvers to produce expressive, detailed figures.

However, due to the size and shape of the tusk, many of these creations are relatively small. This limitation kept many artists from signing their work; only in rare instances and on larger-scale objects do we see signatures. Although Mia’s ivory sculpture of Christ on the Cross is unsigned, three other sculptures have been attributed to this anonymous artist throughout Italy and Spain.

Guns for ivory

The profitable poaching of animals for their ivory has funded African autocrats as well as rebel groups attempting to overthrow them. In fact, the ivory trade has always played into power struggles.

In Central Africa in the 1800s, ivory trading was often linked with the slave trade. Europeans gave guns to Chokwe hunters in exchange for ivory. The firearms made hunting elephants easier, resulting in more ivory harvesting by the Chokwe kingdoms. More guns also led to more armed conflict, generating populations of human captives bound for the slave-holding societies of the Americas: Brazil, the West Indies, and the United States.

The things they carried

Not only was the ivory trade linked to the slave trade in Africa, it sometimes literally went hand in hand. In the 1800s, the East African country of Tanzania was crossed by caravan routes that connected the inland, home to precious commodities, to the coast, where these goods were consumed by urban elites and traded across the Western Indian Ocean. (Mia’s ivory comb from Zanzibar, made in the 1800s, dates to this era of trade.) The most lucrative trade was in ivory and people. And some of that ivory was carried by enslaved Africans. The practice gave rise to the expression “black ivory carries white ivory.”

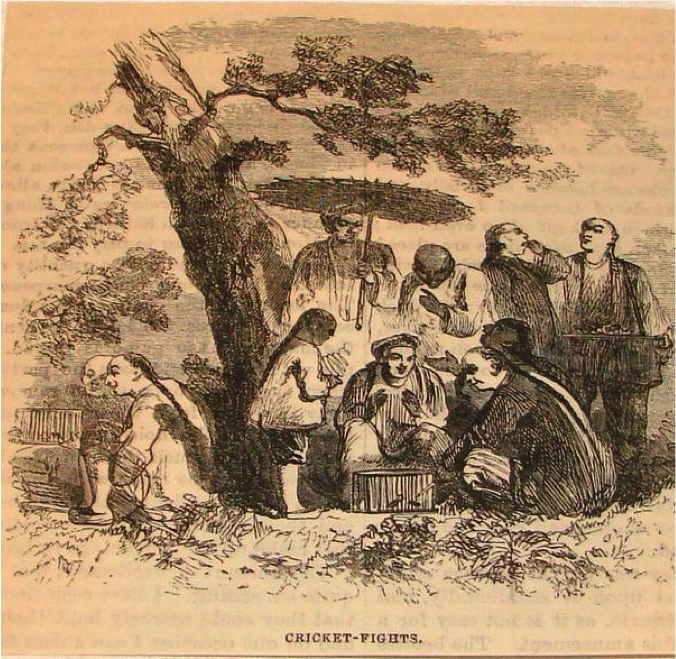

Keeping crickets

Among the utilitarian objects historically made from ivory in China were cricket cages, such as the one on view at Mia in gallery G216. Cricket culture in China dates back at least 2,000 years. So prized were the insects, kept for both their singing and fighting abilities, that their owners purchased elaborate cages to hold them. This one suggests a time when elephants were more plentiful, or less valued, than crickets.

Sculpting drama

In the 1600s, a renewed interest in ivory carving emerged in Europe thanks to new maritime routes along the east and west coasts of Africa. The baroque style, so called for its dramatic, elaborate effects, coincided with this ivory influx, providing European artists with a medium suited for the style of the day. Many began using ivory in extravagant church interiors and to create expressive sculptures, like Mia’s sculpture of St. Jerome, on view in gallery G312. The skill of ivory carving became so popular that, in central Europe and the Netherlands, court positions were created for sculptors who specialized in ivory.

Exotic imports

A century or more ago, roasted coffee in England was as exotic as an elephant’s tusk. Which must be why the silversmith who created Mia’s coffee pot from the workshop of William Fairbourne and Sons, on view at Mia in gallery G350, fused both imported rarities in its design. If you were incredibly posh, like Downton Abbey posh, you’d pull out your sterling and ivory coffee and tea set to show guests your worldly epicurean tastes.

Contributors from Mia include Alex Bortolot, Tim Gihring, Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers, Gretchen Halverson, and Diane Richard.

Newsflash is a occasional series linking current events with objects from Mia’s collection.