For Black History Month, Mia has created a self-guided tour exploring three centuries of art by African-American artists now on view at the museum. Pick up a tour guide on your next visit or take the virtual tour here online.

Gallery 304

Joshua Johnson, Portrait of Richard John Cock, c. 1817

What is the first thing you notice when looking at this portrait? Joshua Johnson was the first-known Black portrait painter in American art history. Born to an enslaved Black woman (and thus enslaved himself), Johnson was purchased by his white father in 1764 and eventually gained his freedom after apprenticing as a blacksmith. As a free man, however, Johnson chose a different path and was not shy about his abilities—in a Baltimore newspaper ad, he declared himself a “self-taught genius.” He found a clientele among the upper middle class of Maryland and Virginia, including Elizabeth and Captain John Cock, who commissioned a posthumous portrait of their son Richard, who died at age 9 in 1817. Johnson’s portrait shows him pointing to a moth—a symbol of his untimely death.

Gallery 302

Henry W. Bannarn, Cleota Collins, 1932

Looking at this portrait bust, how would you describe the personality of Cleota Collins? Born in Oklahoma, Henry Bannarn soon moved with his family to Minneapolis and at 18 he became the first African American artist to win first prize for a painting at the Minnesota State Fair. Scholarships from General Mills co-founder James Ford Bell and the Phyllis Wheatley House in Minneapolis helped him attend the Minneapolis School of Art (now the Minneapolis College of Art and Design), where he created this striking portrait bust of the singer and civil rights activist Cleota Collins. Bannarn completed his education in New York, and his studio at 306 West 141st Street became a creative center and meeting place for African American artists, musicians, and poets during the Harlem Renaissance movement. Bannarn himself became identified with his paintings and sculptures and was admired as a teacher and mentor to younger artists.

Gallery 304

Addie Pearl Nicholson, “Housetop” quilt, nine-block

“Half-Log Cabin” variation, 1974 What textiles do you treasure? What qualities might they share with this quilt? The “Housetop” pattern of concentric rectangles framing a square was uncommon outside of Gee’s Bend, a rural part of Alabama now well known for its unconventional quilts. Addie Pearl Nicholson made her quilt with nine blocks but disrupted the pattern by rotating each block in different directions. Nicholson started piecing quilts when she was 16, eventually with help from her husband, Daniel. They went on to have 10 children, and while they worked in the field the young children would lay on quilts under the shade of a tree, guarded by their dog.

Gallery 374

Kehinde Wiley, Santos Dumont–The Father of Aviation II, 2009

Take a moment to look at this painting. What sparks your curiosity? Kehinde Wiley is known for his large-scale portraits of Black men posing as kings, prophets, saints and other celebrated figures in the tradition of Old Master canvases from the Renaissance and Baroque eras. In transposing Black bodies into the context of traditional European portraiture, the work challenges racial discrimination in the art world and raises issues of identity and self on a global scale. The subjects here chose to position themselves as the two “fallen heroes” in a well-known public monument to Brazil’s pioneering aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont. By depicting these Black men as pioneers of Brazilian aviation, Wiley instills his anonymous subjects with a powerful and heroic identity, essentially immortalizing them in oil paint.

Gallery 375

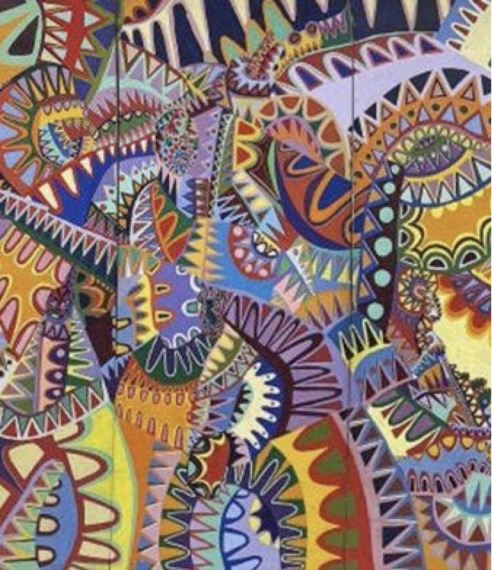

James Phillips, Cosmic Connection, 1971

How does Phillips give visual expression to music in this painting? James Phillips was deeply involved in movements to recognize and communicate Black and African diasporic identities and creativity through the arts. His Cosmic Connection, at more than 17 feet long, is a bursting, cacophonous, and rhythmic homage to visionary musician, composer, and music theorist John Coltrane. He created the painting during a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, as a backdrop to a memorial concert for Coltrane in New York. Imagining an uplifting visual counterpart to Coltrane’s music and soul, Phillips hit on light, explaining, “Sound is sound. I work with the visual manifestations of sound. The visual component to that would be light.”

Gallery 376

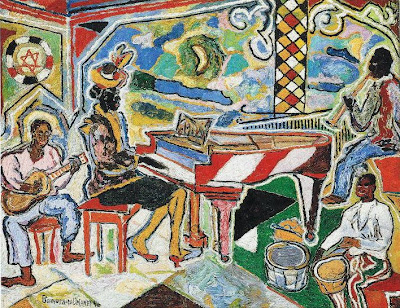

Beauford Delaney, Jazz Quartet, 1946, Private collection

How does Jazz Quartet compare to James Phillips’ Cosmic Connection? Beauford Delaney attended art school in Boston and then moved to New York in 1929. A lover of jazz and blues music, literature and the theater, Delaney befriended and painted many writers, actors, and musicians. He lived in Greenwich Village, inspired by the lively streets and diverse community. His paintings expressed the excitement of city life in vivid colors, energetic lines, and quick brushstrokes. As a gay African American man, he faced discrimination in the United States; Paris was more tolerant. Delaney left New York for Paris in 1953, and he spent the rest of his life working there, moving from figurative to abstract painting. (See Delaney’s “Untitled,” in this same gallery.)

Gallery 377

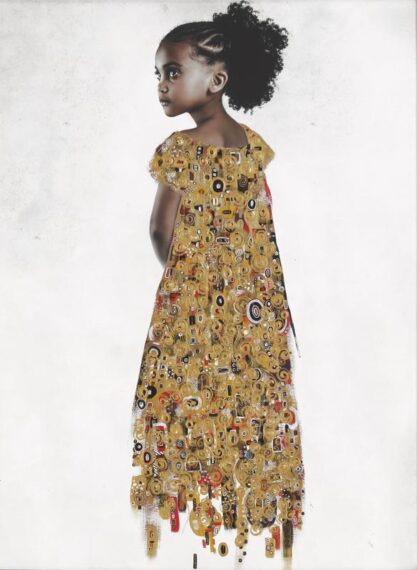

Tawny Chatmon, God’s Gift, 2019

What words come to mind as you look at this portrait? Tawny Chatmon paints, manipulates, and embellishes her photographic prints with 24-karat gold leaf and acrylic paint to create arresting portraits that celebrate Black beauty, identity, and culture. God’s Gift features a young Black child in a glittering gold dress inspired by Gustav Klimt’s lavish portraits of white Viennese women a century earlier. Chatmon grew up in Germany. She was drawn to the Old Master paintings she saw on field trips but was haunted by the negative historical representations and absence of Black figures in European and American art. In Chatmon’s words, this portrait is meant “to act as a counter-narrative and redemptive measure to uplift and elevate Black hair, tradition and culture freeing us from negative stereotypes.” The girl is an ethereal vision, looking up toward the sky and appearing to float in her gold dress like an angel.

Gallery 281

Sonya Clark, Cornrow Chair, 2011

What surprises you about this artwork? Cornrow Chair started with an unexpected encounter of a found object: an awkwardly proportioned chair with curvaceous arms and plain standard legs. To Clark, the chair signified the United States’ uncomfortable history of race relations and its entrenched practice of devaluing labor—often invisible—that props up the economy for the primary benefit of the wealthiest members of white society. To underscore the metaphorical links between this unusual object and seen/unseen members of American society, Clark reupholstered the chair with a showy velvet and striped ticking—a durable industrial textile more often used as an upholstery underlining or mattress cover. Clark then embroidered the back of the chair with stitched cornrows that extend beneath the chair and cascade in a mass of braids which appear to support the chair itself.