Though long neglected, rejected, anonymized, and otherwise diminished, women artists have nevertheless added their voices to art-making throughout time and across cultures. Mia has assembled this tour of art by women, from the historical to the contemporary, to experience in person or online.

Gallery 243

Shahzia Sikander, Arose, 2020

Shahzia Sikander reinvents and challenges the strict formal rules of classical Indo-Persian miniature painting by experimenting with scale and various media, including mosaics. (See examples of such paintings in this gallery.) Her work is informed by voices from South Asian, American, feminist, and Muslim perspectives. Women in Persian miniatures are historically depicted according to stereotypes—as dancers, as objects of desire. Notice how the woman in the nearby painting, al-Mam’un Proposes Marriage (in the case along the wall), is presented. Sikander wants to change the way we look at these women. In this work, mirror versions of the same woman whirl around in a pinwheel, which she calls “the enormous possibility of the feminine spirit.”

Gallery 259

Avis Charley, Think Long, Think Wrong, 2021

Dakota/Dine artist Avis Charley portrays resilient, independent Indigenous women in modern settings. While growing up, she yearned to encounter paintings made by and for Indigenous people in museums, instead of the romanticized and often inaccurate portraits she found painted by non-Native artists. This led Charley to paint authentic representations of Native people living in the contemporary American landscape. She wants her work to inspire present and future generations and to broaden perspectives for general audiences. Charley says, “I create images that I wish I would have seen growing up—beautifully adorned Indigenous women carrying themselves with pride and grace, their dynamic figures coming alive and engaging us with their humanity.”

Gallery 373

Otobong Nkanga, Double Plot, 2018

Otobong Nkanga’s work reflects on the human and environmental legacy of European colonialism on the African continent. The lines that run through the tapestry reference her lifelong interest in mining and the scars it leaves on the land. They represent geographic borders, tree roots, veins of precious ores, as well as the veins of the human body. Nkanga’s lines of silver and copper threads connect literally to the precious metals being mined for objects like cell phones. A glittering image of a solar system superimposed on these lines draws our awareness away from the particular and present to the universal and timeless. At left, a person stands beside a tree, his arms linked to colorful disks that become part of the celestial network. The elements of bodies, land, and plants are literally woven together, reminding us that political decisions have repercussions for humans, geology, and societies. Nkanga interconnects her work with places she has lived and suggests how what happens in one place of the natural world affects another.

Gallery 374

Swoon, Alixa and Naima, 2008

Street artist Swoon creates life‐size wheat paste prints and paper cutouts of human figures, often her friends and family, which she pastes on abandoned buildings, bridges, fire escapes, water towers, and street signs. Her works flake and decay over time, becoming part of the natural collage of the city. This sculptural canvas of salvaged urban materials— scrap metal and wood—wraps around a corner of the gallery, breaking the boundaries of traditionally hung artworks. Here, Swoon depicts the Brooklyn-based poets and fellow street artists Alixa and Naima, who form the duo Climbing PoeTree. Using art and poetry as tools for education, community organizing, and social activism, Climbing PoeTree seeks to overcome destructive elements with creativity. The two women hold each other, eyes closed and unaware of the viewer, who shares in this loving and joyful moment. Just as Swoon places her subjects in the urban landscape, here the urban landscape is placed in a museum gallery.

Gallery 375

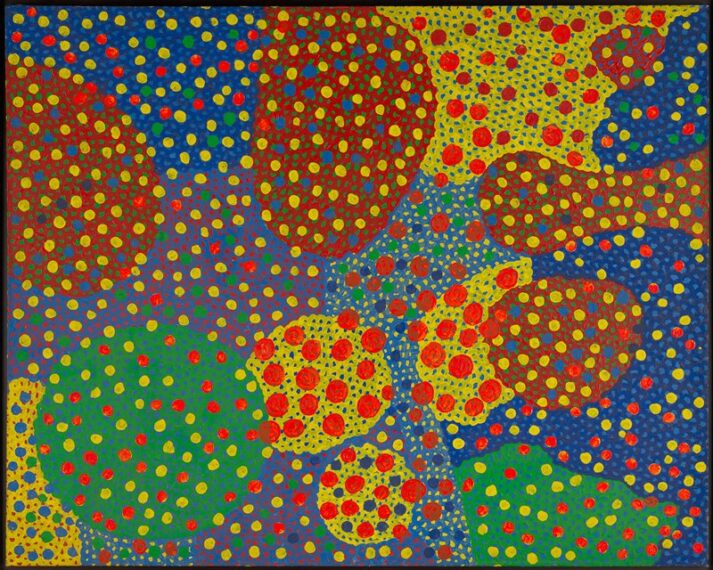

Yayoi Kusama, Untitled, 1967

Yayoi Kusama struggles with controlling her thoughts and emotions. Since childhood, she has experienced hallucinations and obsessive thinking. She often feels surrounded by dots that make up an “infinity net” around her. To help manage her feelings, Kusama creates paintings, sculptures, installations, and more using bright colors and repeating shapes, especially polka dots. In 1977 she admitted herself to a psychiatric hospital and continues to live there, walking to her nearby studio to work on her art every day. She has harnessed her trauma through her work. Now in her 80s, Kusama is internationally known and considered Japan’s greatest living artist. Her Mirror Infinity Rooms, lined with mirrored glass and containing scores of neon-colored LED lights, are featured at many museums. These rooms of infinite lights create an illusion of never-ending space. In this way, Kusama creates an environment that may help viewers experience what a world of “infinity nets” is like.

Gallery 367

Alexandra Exter, Italian Town by the Sea, c. 1917

Alexandra Exter’s work is vibrant and playful in composition, subject matter, and color. She combines the influences of Cubism and Futurism in her painting. Cubism seeks to display several aspects of the same object at once by fragmenting the forms and reassembling them in a new way. It mimics the way we see; our eyes are constantly moving and shifting, seeing multiple views of an object or scene. Futurism focuses on the technical progress of the modern machine age, showing dynamism, speed, and change. In the modern age, life moves faster all around us. As one art critic said, we are looking at the world from a train window, not a bicycle seat. Exter’s inspiration for this work probably came from a visit to Italy in 1914, where coastal towns seem to cling to the hillsides. As a young woman, she had her own studio in Kyiv, Ukraine, and taught other artists. When she moved to Paris in 1924, she became known in the salons, mixing with Picasso and his circle. Exter pushed spatial boundaries both in her work and in her life.

Gallery 357

Philip Webb and Kate Faulkner, Morris & Co., Settle, c. 1800

Kate Faulkner was an Arts and Crafts artist and designer. She worked in a variety of media, including wood engraving, embroidery, wallpaper and fabric design, and gesso, tile, and china painting. Faulkner both created her own designs and interpreted the designs of others. On the settle, a type of bench, she produced delicate floral and sun motifs using carved and gilded gesso. The dense intertwined vegetal forms are clusters of hawthorn and jasmine sprawling under bouquets of lilies, tulips, and carnations. The sides are adorned with cherry branches. Faulkner’s detailed interpretations drew deeply from nature, matching the charm of the Morris & Co. design ethic. Living in a world that did not widely encourage female design practitioners, Faulkner compiled an impressive portfolio of creations. Many of them are still in print and remain popular to this day. This settle is unique to Mia, with no other object like it currently in the United States.

Gallery 301

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Place I, 1945

Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the most admired American Modernist painters of the 1900s. She began with studies of traditional painting techniques, but a later teacher, Arthur Wesley Dow (see his painting on the same wall), greatly influenced the direction of her art. Dow discouraged copying nature and insisted that pleasing landscapes could be created with “a few lines harmoniously grouped together.” Beauty was more important to him than accuracy. His ideas helped O’Keeffe develop a visual language to express her feelings and ideas, a major characteristic of modernism. O’Keeffe is also known for paintings of New York skyscrapers, as well as large-scale depictions of flowers. In the summer of 1929 she first traveled to northern New Mexico and experienced the stark landscape of the American Southwest. For the next two decades, she spent most summers living and working there, inspired by her surroundings. Among her favorite places to paint was a site she called “the Black Place,” a barren stretch of hills in Navajo (Diné) country.