Owariya Yonejiro was born in 1839 in old Edo, now Tokyo, into a way of life on its way out. His father, a wealthy merchant, had essentially purchased samurai status, becoming part of the ruling class in its waning decades of power. At 11, he was apprenticed to one of the last great masters of ukiyo-e, or woodblock prints, then Japan’s signature art form. The master gave him the name Yoshitoshi, linking him to the most important line of woodblock artists in their final burst of glory—indeed Yoshitoshi would be the exclamation point.

That Yoshitoshi was fascinated by ghost stories is not surprising. Ghosts were ever-present in the old Japan he cherished, a kind of shadow society comprised of women who had died in childbirth, the violently slain, and others who had died too soon, along with spirits who were actually the malevolent manifestations of living people’s anger or jealousy. And then there were the contented dead, happy to help the living from the other side. These ghosts were complicated, in other words, unlike the white-sheeted mutes of modern-day America, who just like to move the furniture around. They were reminders, in their sudden and ephemeral violence, of the fragility of life.

Yoshitoshi seems to have been haunted by death his whole artistic life. He was rattled by the passing of his father and his master as well as the fading of the old order in Japan, beginning in the 1860s, and the violence that followed. He is said to have participated in the long sessions of candle-lit yarn-spinning that were popular in his day, called One Hundred Ghost Stories, in which people took turns telling, well, one hundred ghost stories, extinguishing a candle after each one. He made his name with bloody prints depicting battles and murders and, yes, ghosts, which were immensely popular among a people at war.

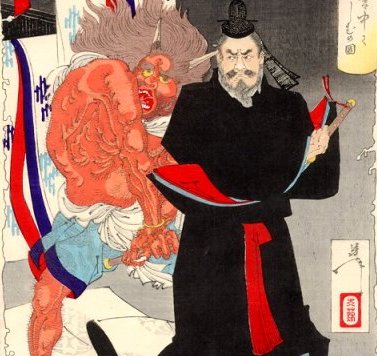

A detail of a print from Yoshitoshi’s “New Forms of 36 Ghosts” series, featuring a demon attacking a nobleman who appears merely irritated as he reaches for his sword.

But it was toward the end of his life that he most indulged his affection for ghosts. He spent three years on a series called New Forms of 36 Ghosts, in which he conjured the most novel of ghost stories—spirits transformed into a heron, a badger, a cherry tree, and smoke. Then he was dead himself, in 1892, before the last prints were published. He was only 53, starved of money and companionship. He was the last great artist of his kind, a burden he seemed unable to bear, and is said, in his final year, to have invited friends to a gathering of artists who in fact did not exist—he had become delusional. His death, like the ghosts he created, suggested an unfortunate end, an era cut short.

Mia recently acquired a collection of some of Yoshitoshi’s best-known works, including prints from the 36 Ghosts series. His work is suddenly popular again, among collectors. His ghosts, embodying the transitory nature of life, the precarious state of existence, have ironically outlived their creator, their immortality all but ensured.

Top image: Detail from a print in Yoshitoshi’s New Forms of 36 Ghosts series in which a demon loses a limb in a fight, only to escape with it, disguised as an old woman.