The Incredible, Forgotten Life of Painter Bob Thompson

January 29, 2026—When he was 18, Bob Thompson thought he might become a doctor. His mother, a teacher, wanted as much for her son. His father had died. He was depressed, living in Boston with his sister, and lacking other ideas for how to move forward. In 1955, he enrolled in a pre-med program at Boston University.

Thompson was an art student by the next year. Pre-med had so bored him, so he leapt to the next thing, as he’d continue to do for the rest of his tragically short life. At 22, he had his first solo art show in New York.

Bob Thompson in his Manhattan studio from the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Thompson held nothing back. His “riffing,” as he called it, on historic paintings, his shifting techniques, his spontaneous approach, it’s all there on the walls, as curious and colorful as Thompson himself.

“I paint many paintings that tell me slowly that I have something inside of me that is just bursting, twisting, sticking, spilling over to get out,” Thompson once said. “Out into souls and mouths and eyes that have never seen before.”

The Bohemian Abroad

Thompson spoke the improvisational language of jazz. He played the drums and, in New York, befriended bassist Charlie Haden, saxophonist Ornette Coleman, and other experimental musicians spearheading the “free jazz” movement. He knew writers like Allen Ginsberg, too, and by the late 1950s, he was attending some of the first “happenings,” in which artists of all kinds would perform spontaneously with the participation of the audience.

Thompson was a bohemian, but he had a thing for Renaissance and Baroque art. When he moved to France in 1961, it was to study these works at the Louvre museum in Paris and elsewhere. In art school, he had begun to copy the paintings of Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca, and other Old Masters, and when he moved to Europe, he began to turn them on their head.

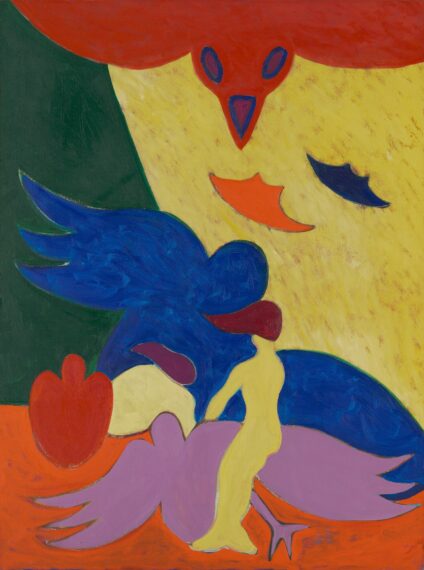

Bob Thompson’s “The Wind” from 1963. Thompson frequently depicted birds, perhaps as symbols of freedom and the ultimate flight of death.

Thompson’s Homage to Nina Simone shows nude men, women, and children grooving to music in an idyllic, park-like landscape—a twist on Nicolas Poussin’s painting Bacchanal with Lute-Player, from around 1630, which Thompson had seen in the Louvre.

Thompson had been on a tear, returning to New York with a huge trove of paintings like this, which established him as a kind of genre unto himself: a Black artist who deconstructed, reinterpreted, and updated art by white artists for a hipper, groovier time.

Like Jean-Michel Basquiat in the 1980s, his talents broke barriers even as they enabled his vices. The art world held out its charms—money, fame, drugs—and he turned none of them away. Thompson painted his tribute to Nina Simone, the legendary singer and pianist, in 1965. The following spring, in Rome, he died from an overdose. He was 28.

In his short life, Thomas produced more than a thousand paintings—three times as many as Rembrandt and perhaps 30 times more than Vermeer. But he is almost forgotten now, outside of connoisseur circles. His work and its visceral appeal suggest he knew that we live in our flesh, among the pleasures and pain it affords us, and we die there, too. He might be disappointed that he is not around—to paint more, to burnish his legacy—but not surprised.

Learn More

Explore more art by Black artists in Mia’s collection.

Exhibitions and gallery installations at Mia rotate regularly. If you’re visiting to see a specific artwork, please contact us in advance to confirm it’s on display.