By Tim Gihring //

In the 1620s, Rembrandt van Rijn and Jan Lievens were both in Leiden, the small town in the southern Netherlands where they had grown up. They were both teenagers, Rembrandt just 15 months older than Lievens. They had apprenticed with the same master painter. They shared models and possibly a studio. They even modeled for each other. They were friends and rivals—frenemies.

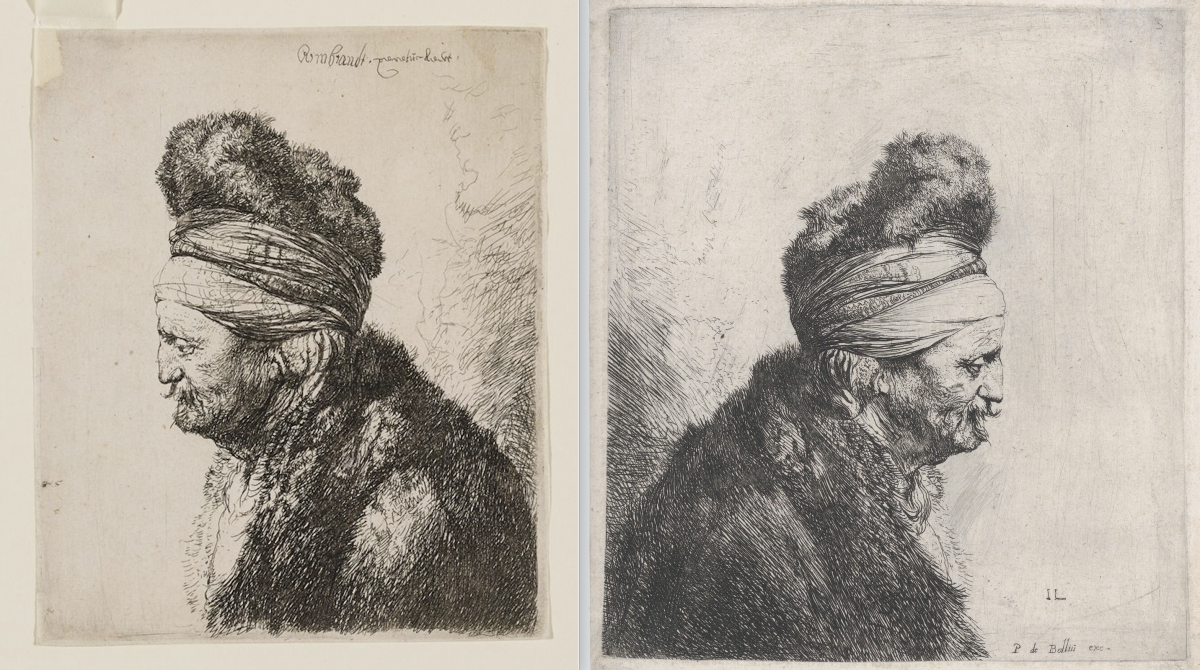

And for a long time, they copied each other. Lievens was inspired by Rembrandt, for example, to etch a series of imagined portraits of men in fanciful dress. Rembrandt, in turn, copied all four of them. When Lievens experimented with scratching paint, using the butt end of his brush, Rembrandt copied that, too. Back and forth, they imitated each other’s work—Samson and Delilah, Christ on the Cross, The Raising of Lazarus—with Rembrandt apparently backdating some paintings to suggest he was the leader, not the follower.

As shown in the new exhibition “Rembrandt in Conversation,” now up at Mia, the artist long depicted as a singular force of imagination spent much of his life in creative dialogue with fellow artists, borrowing ideas even as others borrowed his. “The idea of the lone genius in the attic was never really true,” says Tom Rassieur, Mia’s John E. Andrus III Curator of Prints and Drawings, who organized the Rembrandt show. Indeed, even when Rembrandt was alone, working in his studio, he was never really alone.

Dueling images of rat-poison peddlers from the exhibition “Rembrandt in Conversation,” at left by Cornelis Visscher from 1655, at right by Rembrandt from 1632. Both are in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The line between inspiration and emulation in the arts has often been thin, but in the 1600s it was practically nonexistent. Artists were expected to emulate their masters, as called for in the foremost art text of Rembrandt’s time, the Schilder-boeck, or Book of Painters, published by Karel van Mander in 1604. “The fundamental way an artist learned was by copying,” Rassieur says. “If a student came to an artist’s workshop to learn, chances are he’d spend the first year making copies of prints.”

Eventually a student would be taught to paint in the master’s style, with the idea that he would continue to paint like this until, with any luck, the student could outdo the master. But that would take time: To express your ingenium, van Mander says, you first need your studium.

Rembrandt was a master, first of all, of studium. It helped that he was in the right place at the right time. Amsterdam was like New York then, the center of the art market, where Rembrandt could see masterpieces on the auction block. “One of the classic stories about Rembrandt is that he went to see a Titian painting at auction, a self-portrait,” Rassieur says. “He made a little drawing of it, noted how much it sold for, then went home to make his own version.”

If he was not the first artist to exploit this unprecedented access, he was certainly among the most devoted. The prominent patron Constantijn Huygens, who saw the early promise of both Rembrandt and Lievens, noted that they had yet to visit Italy, in the tradition of aspiring artists, to see the Old Masters. “They are carelessly content with themselves,” he wrote. Rembrandt never did leave Holland. He had everything he needed right there.

Rembrandt collected, too—as much as he could afford and more. It’s one of the reasons he was bankrupt by 50. Even then, he kept collecting, amassing some 8,000 prints and drawings. Yet he seemed to need these works, especially from masters like Albrecht Dürer and Lucas van Leyden, whose exquisite engravings and etchings had set the standard a century earlier. He needed the benchmark. He needed to measure himself against someone—everyone, in fact. It hardly mattered if they were dead. “He was incredibly competitive,” Rassieur says. “He’s competing against his equals and his teachers, the artists of the past and the artists of his time.”

Emulation to Evolution

A series of prints in the exhibition show how Rembrandt, in the 1650s, transformed van Leyden’s depiction of Christ before Pontius Pilate, the dramatic moment in the Bible when the Roman governor calls on the crowd before him to decide Christ’s fate, literally washing his hands of the matter. Rembrandt had seen an engraving of Raphael’s iconic School of Athens fresco, in the Vatican, and he borrowed much of its composition for this reworking: the symmetrical, rectilinear architecture; the central placement of the protagonists, framed by a doorway; the statuary flanking the action. He made a Raphael of a van Leyden, with a few touches from the Amsterdam Town Hall (now the Royal Palace), which was then under construction, a neoclassical monument to Amsterdam’s self-image as the Rome of the north.

A couple years later, Rembrandt changed the work, literally obliterating the crowd by scraping it off his copper printing plate. He was angry and despondent. After his wife’s death he was unable to remarry without financial penalty, given the terms of her will, and when his new partner became pregnant out of wedlock, the church reacted harshly. Rembrandt, in conversation only with himself this time, turned the image of Christ’s judgement into an anguished reflection on judgement itself.

He further humanized Christ—now a sinewy, half-naked figure—and replaced most of the mob with black pits, what Rassieur calls “a bottomless opening leading to hell.” Viewers of the image now look directly at Christ. They are essentially part of the crowd, asked to render the verdict that Pilate refused to make. Forced to reckon with the way we judge each other and the consequences of unfair conclusions.

At left, Rembrandt’s Christ Presented to the People (Ecco Homo) circa 1653; at right, his reworking of the image from 1655. Both in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The van Leyden that became a Raphael is now indisputably a Rembrandt. Rembrandt was competitive most of all with himself, boldly changing directions as he developed. That was his ingenium. Not that it was obvious at the start, when Lievens and Rembrandt were young upstarts and Lievens seemed the more precocious painter.

Huygens, writing around 1630, suggested that “Rembrandt is superior to Lievens in his sure touch and liveliness of emotions. Conversely, Lievens is the greater in inventiveness and audacious themes and forms. … He has an acute and profound insight into all manner of things.” But Huygens also sensed that Lievens was limited by his temperament, “… his stubbornness, which derives from an excess of self-confidence. He either roundly rejects all criticism or, if he acknowledges its validity, takes it in bad spirit.”

Lievens eventually left for London, in 1631, to become a court artist. He went on to serve the courts in Berlin and The Hague, painting portraits and palaces. His style hardly developed. “Lievens chose the money,” Rassieur says. “His early work is very interesting and then suddenly you don’t want to look at it anymore.”

Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam and never left, but he evolved several times over. In the 1640s and ’50s, when both artists were once again in the same city, their styles diverged completely. While Lievens was painting the rich and famous, Rembrandt was consolidating the dark and dramatic vision for which he is perhaps best known, and spiraling toward bankruptcy.

Over the next couple centuries, Rembrandt’s reputation would rise as much as Lievens’ would decline. Rembrandt’s relationships to the artists he emulated would be increasingly diminished, to support the romantic notion of the lone genius. Some of Lievens’ best work would be misattributed to Rembrandt. By 1936, when the British bio-pic Rembrandt came out, the die was cast. Played by the intense Charles Laughton, Rembrandt misses the funeral of his wife and is instead in his studio, painting her portrait. He is alone except for his ingenium. He is conjuring his work out of nothing.