This is a transcript of The Object podcast, episode seven, first broadcast in June 2019. You can listen, subscribe, and find all-new episodes here, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

In 2009, the painter Kehinde Wiley flies to Brazil. He’s there to make some portraits, in his signature style: painting brown-bodied men in the heroic manner of old European portraits—like Napoleon on his horse. He’s the artist selected by former President Obama for his official portrait.

So he goes looking for some models. He’s looking in the favelas, the poor neighborhoods in the hills around Rio. And he finds a couple young men who agree to pose.

The monument to Alberto Santos-Dumont at the Rio de Janeiro airport in Brazil.

Now, Wiley had seen a heroic statue in Rio, of a naked man with wings. He looks like Icarus, the impetuous Greek god who flew too close to the sun. It’s not a hard statue to spot—it’s right outside the airport.

The monument is dedicated to a guy named Alberto Santos-Dumont. And he’s pictured on it, too, just below Icarus. A dapper young man with a mustache. His eyes are cast down—he looks like he just dropped his ice cream cone. But he’s one of the most famous people in Brazil. The airport is named after him. He’s kind of a god. Because in Brazil, if almost nowhere else, Santos Dumont is considered the first person ever to fly.

But the really interesting thing about this monument is that there are two more guys at Icarus’s feet, and they’re crumpled up—dead, supposedly, from failed attempts to fly.

So Wiley asks his models if they’d like to pose as this statue, and they say yes, sure. And Wiley takes their photo and paints them. And now the painting is hanging in the Minneapolis Institute of Art. This huge picture of two brown-bodied young men in shorts and T-shirts, staring out at you.

But here’s the thing: they’re crumpled up on the ground.

The models had decided they wanted to be the dead guys. The ones who didn’t make it.

•••

It’s 1891, and Alberto Santos-Dumont has just moved from Brazil to Paris with his family. He’s 18 years old, and he’s rich. His parents owned a coffee plantation, back in Brazil, and now they’re here, in Europe. So Alberto starts looking for something to do, because he doesn’t really have to do anything.

He begins racing motorized tricycles. Which are not the tricycles you’re thinking of—they’re for big people, okay. But that’s not interesting enough for Santos-Dumont. He’s a really good mechanic. So he starts building hot air balloons.

The French are kind of reluctant to work with him at first. He’s small—just a little over five feet tall, maybe a hundred pounds. And he’s kind of a dandy, going around the cafes in a high-collared shirt and a droopy white Panama hat. In French you would say he’s a flaneur, or a boulevardier.

But he finds a couple of balloonists to help him build his first gasbag, as they called the balloon part. And he names it the Brasil.

It’s a lot of fun, being Santos-Dumont. It’s a lot of fun being the friend of Santos-Dumont. He’s flying around with a picnic of cheeses, ice cream, cake, champagne—which is extra bubbly at the heights they’re ascending.

But this still isn’t interesting enough. So he attaches a car engine to a balloon. And he reshapes the balloon so it’s more like a fat cigar. And puts a rudder on it, so he can steer. He’s created an airship—a dirigible, a blimp. He makes one after the other. And he calls them Number 1, Number 2, Number 3, etc., as he’s making them bigger, better, faster.

At the end of the century, Santos-Dumont is the only person in the world flying around in airship.

•••

Airship Number 5 ends up slamming into a hotel in Paris. Santos-Dumont is just hanging there, suspended in the air with his broken flying machine, until some firemen rescue him.

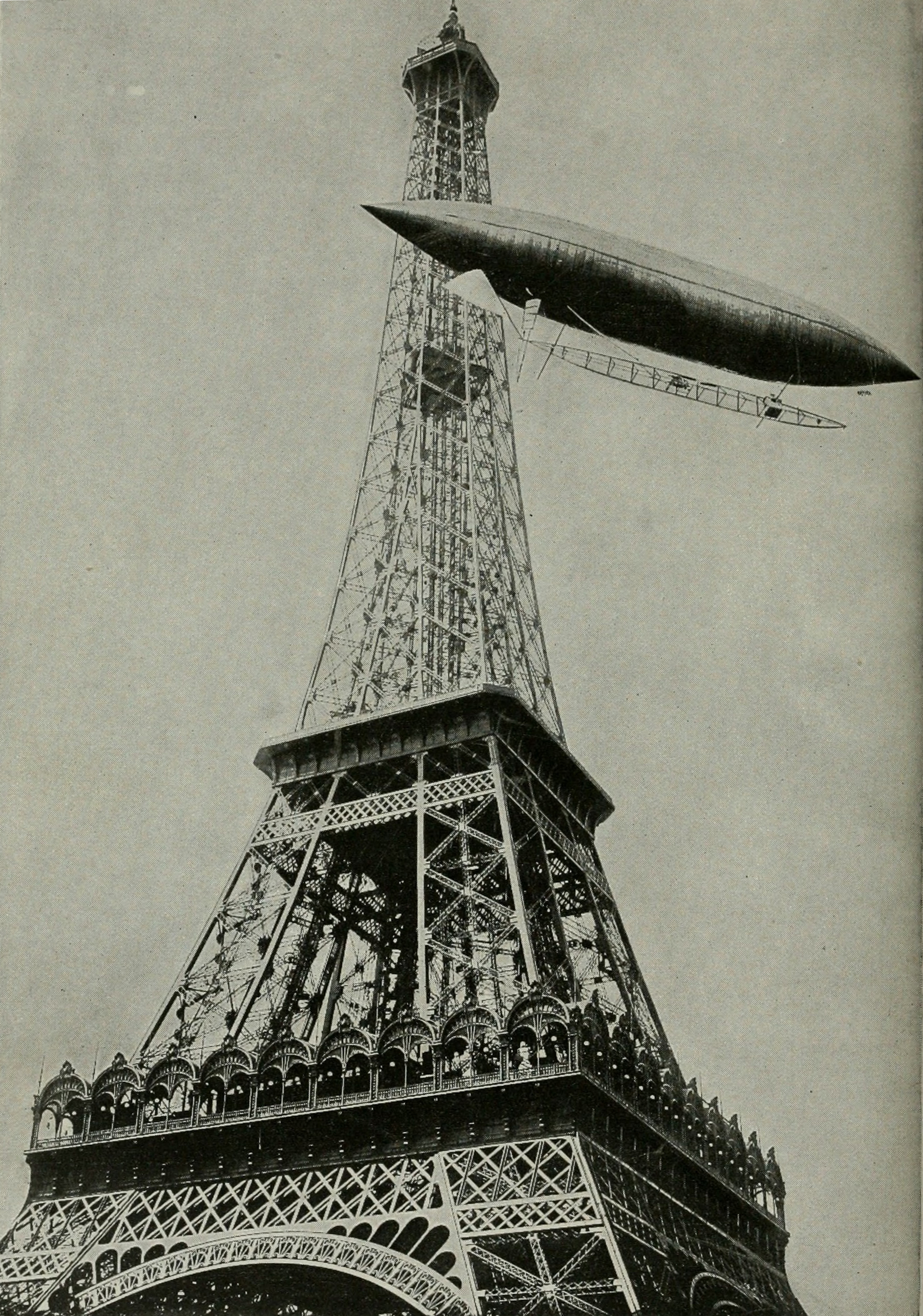

But airship Number 6, this he ends up flying around the Eiffel Tower, in 1901. And now, after less than a decade in Paris, Santos Dumont is famous. He gets Louis Cartier, the jewelry maker, to make him one of the first wristwatches, so he can easily tell time while he’s flying around in his airships. And he builds a small, personal-size airship that he can sail right down the boulevards of Paris, and tie up on a lamppost outside a café, like it’s some kind of horse. And then go in for lunch.

He starts having these aerial dinners, too, at his house. At first he hangs the table and chairs from the ceiling, with wire. So you’re suspended up there, trying to eat. But the ceiling collapses. So instead he builds these dinner tables and chairs with really long legs, so the chair is on the ground but you’re sitting like 10 feet in the air, drinking champagne. He says he just wants to share the experience of flying.

And he really means it. He doesn’t take any money from his flying career, from prizes or patents—he gives a lot of it to the poor. Because he thinks of flying as a gift to the world, a kind of great equalizer, something that will eventually bring us all together. As if, once we pull ourselves off the ground, all that earthly pettiness will fall away, and we’ll be free.

•••

Eventually, he starts experimenting with airplanes. Which is the big prize, right. He knows about the Wright Brothers, across the pond. And their experiments with flying. But they’re nobodies—from Dayton, Ohio—and nobody really knows what they’re up to.

So on the morning of October 23, 1906, Santos-Dumont wakes up. Puts on his high-collared shirt and tie. And hauls this biplane he built into a field near Paris. He stands in a kind of basket to drive it, and it takes off. It flies about 200 feet, about 16 feet off the ground. Maybe a thousand people watch him do it, it’s filmed—you can watch it on YouTube.

It’s the first real flight of an airplane, says everyone involved. But here’s the thing. The Wright brothers had made their first flight three years earlier, in 1903.

And yet, that doesn’t stop anyone at the time from glorifying Santos-Dumont. He’s the most famous aviator there is. In fact, when the Wright Brothers made their first flight, their own local newspaper said, “Dayton Boys Emulate Great Santos-Dumont.”

•••

Now, there are a lot of reasons why people wanted to elevate Santos-Dumont over the Wright Brothers. The Wright Brothers worked kind of in secret, because they didn’t want their ideas stolen—they wanted the patents. Santos-Dumont published his designs. He wanted everyone to know about airplanes, so they could set themselves free.

Brazilians had their own reasons for celebrating Santos-Dumont. They had only been a republic for a few years when Santos-Dumont made his first flight—they were still thought of, in Europe and the U.S., as being a kind of colony. Backwards. And here’s Santos-Dumont, the elegant dreamer, the toast of the skies. That meant a lot to Brazil, and still does. Textbooks there say he was the first to fly, and they have a point.

If you run the hundred-yard dash faster than anyone ever has, but no one knows it except you and your buddies—who cares, right? It doesn’t really count. Do it in the Olympics, now that’s a different story. And that’s what Santos-Dumont did, he flew for the judges, he won a prize. He was official.

But whatever. In fact, it’s almost better that the United States wants to take this honor and give it to the Wright Brothers—it’s always better to be David than Goliath.

•••

It’s 1910 now, and Santos-Dumont has built a plane small enough to carry around in the back of his car. But he’s flying it one day and it snaps apart—a hundred feet in the air.

He falls and has vertigo and double vision and a doctor says he has multiple sclerosis. He stops flying.

Then World War I happens, and the airplane is now a war machine. The thing he thought would save the world is helping tear it apart. In 1920, he sails to Rio de Janeiro and digs his own grave. Literally. He digs a hole in a cemetery. Gets a replica made of a statue of himself that was put up in Paris, so he can put it by the hole. And transfers the remains of his parents to his own gravesite, leaving a little room between them for himself.

And then he goes back to Europe. He makes a few more inventions, like some motorized skis to carry himself up a mountain, and a slingshot to shoot a life preserver out from a boat. But mostly he’s in and out of sanatoriums in Switzerland and France.

In 1928, he goes back to Brazil. He’s feeling a little better. And the Brazilians are ready for him. He’s been forgotten in much of the world, but here he’s still a hero.

As his ship pulls into Rio, a plane flies overhead. It’s carrying a dozen of Brazil’s most prominent scientists, a tribute to the great aviator. And it explodes. His country’s greatest scientific minds are dead.

He never gets over this. And in a few years, when Brazil too is using airplanes to blow itself apart in a civil war, he feels even worse. He blames himself, for helping invent this thing. One day he pulls out two red ties he used to wear while flying around Paris, and hangs himself.

•••

The medical examiner who comes to see him, cuts out his heart and keeps it in a jar of formaldehyde. Eventually it goes on display in Brazil’s Air and Space Museum. Inside a small, gold-plated globe of the heavens. Held by a statue of a man much like Icarus, his arms raised to the sky.

We know what happens of course when Icarus flies too close to the sun. He plummets. He dies. Like the men crumpled up on the statue back in Rio. But at least he saw the sun. He got there, when no one thought he should.