As a curator in Mia’s Department of Prints and Drawings, I am a self-confessed “paper” person. I love the feel of good paper, the elegant mark of ink on the page, the palpable three-dimensional relief of a well-preserved woodcut. I favor paper books and newspapers to digital versions, and nice stationery and handwritten notes over texts and emails. Of the 13,004 pictures on my iPhone, the images related to paper — drawings, prints, books, illuminated manuscripts, parchment, watermarks — far outnumber the snapshots of my children at hockey games, soccer games, and dance recitals.

Within my storehouse of art photos, a new subtheme (actually more of a personal obsession) has emerged: images of paper in paintings. For centuries, artists have spilled a great deal of lead-white paint in this tiny category of representation, which can include a single sheet or pages of an open book. Through this unique window, we can see artists demonstrating their skills in observation and illusionism, delighting in capturing the subtle texture and varied color of old rag paper, and reveling in the extraordinary beauty and knowledge bound up in an early printed book.

Aureliano Milani, “Miracle of the Madonna of the Fire,” c. 1725, oil on canvas, Mia, The John R. Van Derlip Fund 71.46. A detail of the woodcut wafting among the flames is shown above.

At Mia, one of my favorite pictures with painted paper was recently put back on view, Aureliano Milani’s Miracle of the Madonna of the Fire, which he painted in Rome in 1725 (gallery G330). It illustrates an extraordinary event some 300 years earlier. On the night of February 4, 1428, a devastating fire broke out in a schoolhouse in the northern Italian town of Forlì. No one was killed, but eyewitnesses reported that everything was destroyed — except, by some miracle, a woodcut. The single sheet of paper represented “Our Lady.”

In Milani’s depiction, precious schoolbooks are scattered in the foreground, along with a writing board and scraps of paper. A student runs with a stack of leather-bound, bookmarked tomes that he has managed to rescue (bless him!). Members of the bucket brigade and a couple of schoolboys look up in awe to see a print fluttering to safety, unharmed. An older man dressed in black, at right, points out the miracle to the viewer. This is Cardinal Fabrizio Paolucci, the patron of Milani’s work, who was born in Forlì 120 years after the famous fire. The miracle remained a proud moment in his hometown’s history, making it an ideal subject for the decoration of his family’s chapel at San Marcello al Corso in Rome. (Mia’s picture is a highly finished modello for the larger, almost identical work hanging, in situ, in the chapel.)

The original woodcut “Madonna of the Fire (Madonna del Fuoco),” c. 1400–25. At right, the Chapel of the Madonna del Fuoco, in the Cathedral of Santa Croce, in Forlì, Italy, where the woodcut is a treasured icon.

The 15th-century woodcut featured in Milani’s painting survives to this day. Now called the Madonna of the Fire (or Madonna del Fuoco), it is an icon, a treasured possession of the Cathedral of Forlì, where it resides in its own chapel and is credited with granting miracles. The original print, some 20 inches high, was made by an unknown artist and shows the Virgin Mary and Christ Child surrounded by smaller scenes of the life of Christ, saints and disciples, and the sun and moon. For simplicity’s sake, Milani depicted just the Virgin and Child flanked by the sun and moon. Milani’s Madonna, rather than looking at the Child, appears to look out at the flames enveloping her in the painting, and seems almost to command her paper support to fly away.

Using the simple outlines and sentimentalism of traditional devotional woodcuts, Milani captured the humble quality of the kind of religious prints that were tacked up in countless homes and classrooms at the time to inspire prayer and devotion. By making the paper look flimsy, weightless, and tattered, Milani implies that the print is fragile and cheap, underscoring the very miracle of its survival.

Jusepe de Ribera’s portrait of Euclid, c. 1630–37, oil on canvas, at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.26. At right, a detail of the book he’s holding, a 1572 edition of his “Elements.”

Another fine example of paper being pictured in paintings is Jusepe de Ribera’s Euclid at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in Los Angeles. It was executed in Naples in the 1630s. The ancient mathematician, in tattered clothing, displays a large mathematical treatise. The spotlit diagrams and typography in Ribera’s painted books are detailed enough to identify the particular volumes: the Latin edition of Euclid’s Elements published in Pesaro, Italy, in 1572. I love the tangible presence of the paper, the thick pages, the cream-colored margins and gray-toned printed sections. The folds, ripples, dents, and curling edges tell us this book has been well-read.

Detail, Pieter Codde, “A Young Man Smoking a Pipe in His Study,” c. 1630–33, oil on panel, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, P.240

Moving north to Amsterdam we find Pieter Codde’s A Young Man Smoking a Pipe in His Study (detail, c. 1630–33, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille). The picture is a splendid symphony of whites, grays, and browns. It represents a young man taking a break from his studies to smoke a pipe. Brooding, with a heavy head leaning on his hand, he is thought to be an allegory of melancholy. Here the curling pages of the book and its haphazard positioning on the desk suggest distraction and procrastination.

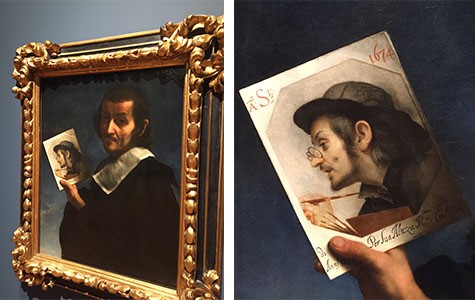

Carlo Dolci’s “Self-Portrait,” 1674, oil on canvas, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, 1890.1676, and a detail of the other self-portrait he’s holding.

Carlo Dolci’s 1674 self-portrait from the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence, recently on view at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, is a clever riff on the theme of painted paper. In the larger portrait Dolci presents himself as a gentleman artist, fashionably dressed in a black silk coat with a wonderful white linen collar. In his hand is a second self-portrait, a signed and dated drawing that shows him in profile, wearing casual attire and glasses, working intently on painting.

Francesco de Mura, “Self-Portrait,” c. 1740, oil on canvas, Mia, The John R. Van Derlip Fund 62.48

Francesco de Mura’s Self-Portrait (c. 1740) at Mia (gallery G307), likewise shows off the artist’s sophistication and status through fancy dress. At the same time, de Mura demonstrates his intellect by displaying a red chalk drawing he made depicting Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and patron of the arts.

Detail, Simon Marmion, “Life of Saint Bertin,” 1459, oil on panel, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, no. 1645A

Finally, there is Simon Marmion’s Life of Saint Bertin (1459), which I photographed at Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie in March. Among the assorted miniature papers and prayer books in this sprawling altarpiece is a scene depicting the construction of a new abbey. A notary is shown reading a long letter or contract, most likely a piece of parchment. The monks and wealthy noblemen listen solemnly to the recitation of the authoritative written word. I love the shimmer of the gold and burgundy brocade coat, the five o’clock shadow faintly darkening the monks’ tonsured heads, the red wax seal dangling from the document. But I might like the two realistic folds on the underside of Marmion’s creamy smooth parchment best of all.