By Tim Gihring //

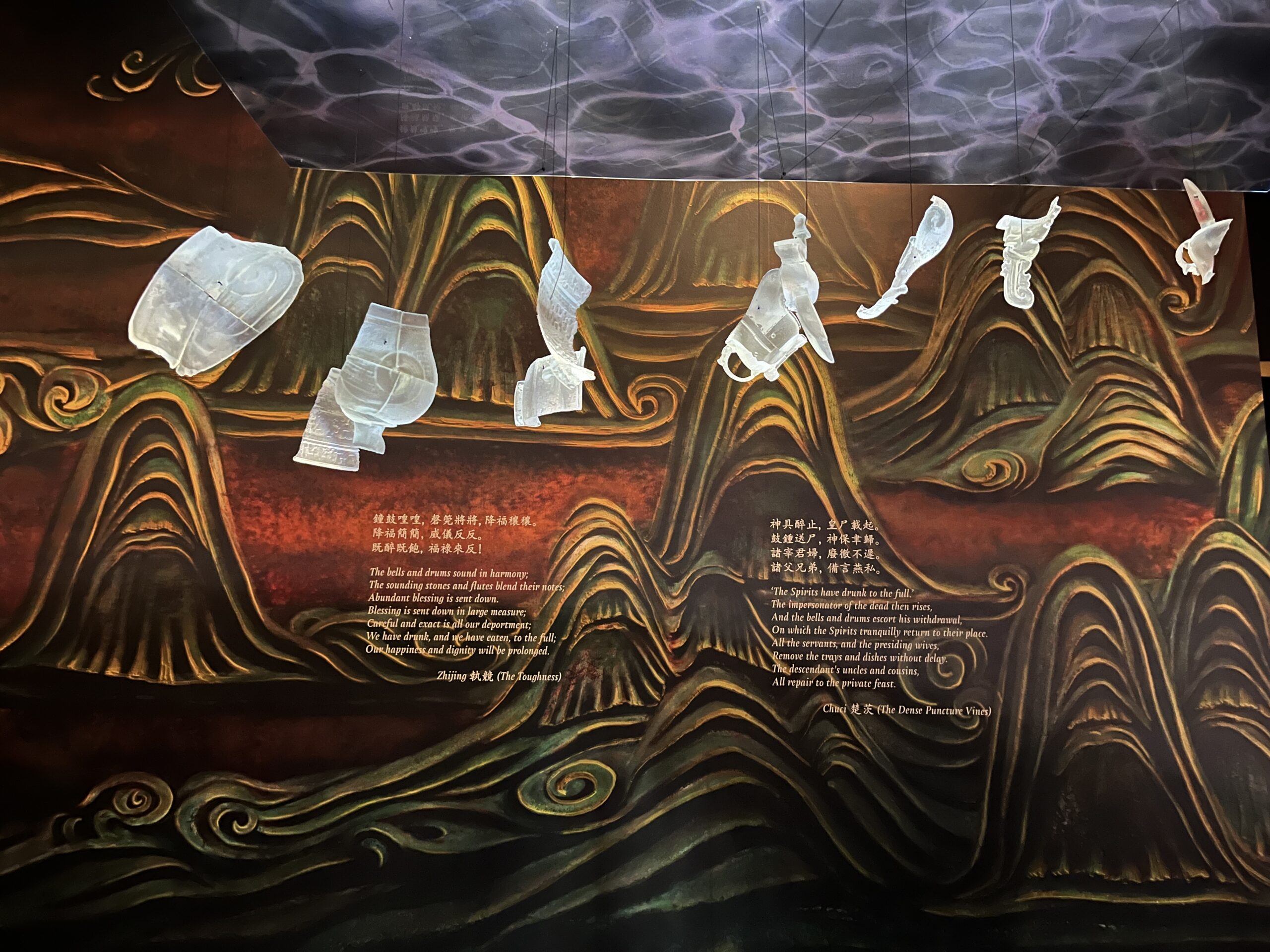

When Tim Yip was conceiving the look of “Eternal Offerings: Chinese Ritual Bronzes,” Mia’s multimedia show of delicately inscribed vessels made for archaic ceremonies, he suggested including fragments of objects at the outset of the exhibition. He didn’t suggest why. Yang Liu, Mia’s curator of Chinese art and chair of its Asian art department, worked out their symbolic meaning: when visitors encounter the fragments, their knowledge—or memory—of ritual bronzes is incomplete. Fragile. Fragmented. At the end of the show, they find that the fragments form a whole.

Sammy, at right, at the opening of “Eternal Offerings” with Tim Yip and Katie Luber, Mia’s Nivin and Duncan MacMillan Director and President.

How to make the fragments proved a harder puzzle. The museum reached out to a professor of sculpture at the neighboring Minneapolis College of Art and Design, who could perhaps enlist his students. But there wasn’t enough time. The museum then approached a local 3D printing company, but the quote was quite high. With the exhibition opening in just a few weeks, the illusory fragments remained just that.

Then, in late January, Liu and his family were invited to a Lunar New Year party at the home of Mia patrons Bob and Lee Rucker in Eden Prairie. Liu noticed the many 3D-printed objects in the house, including a life-size violin. All of them had been made by the Ruckers’ son Sammy, a sophomore in high school. Sammy had been experimenting with 3D printing at home, making everything from the violin to children’s toys to a miniature version of a moai—a giant head sculpture—from Rapa Nui. He even built the printer itself.

Liu sensed an opportunity—for the museum, the exhibition, and the family. “I mentioned that we’ve been trying to create these fragments,” says Liu. “I asked if Sammy would be willing to help.” Within a week, he was on the job.

Mia photographer Charles Walbridge sent him the specs. When the first tests suggested the plastic material used by the printer lacked the elegant translucence Yip was going for, the Ruckers acquired a new machine. Sammy worked at it all day—it took eight hours to print one part. At school, he tracked the progress using a camera installed near the printer.

Within a few weeks, and just in time, Sammy was done. For the opening party of the exhibition, he put on a suit and mingled with Yip and Liu. Though Sammy downplays his role as merely a matter of mechanics, the family is grateful that Liu and the museum put their trust in the teen’s hands. It was, his mother says, an ideal project. “The community involvement, the blending of art and technology, this was a perfect fit,” says Lee Rucker, and a gift the family was happy to contribute.