By Diane Richard //

“It’s the only decapitation painting I did.”

Not many living artists can claim that—paintings of beheadings not being, perhaps, as popular as they once were. Then again, not many living artists have a painting in the same gallery as Judith and Holofernes (1599) by Baroque master Caravaggio (Italian, 1571–1610), on view in Mia’s Bell Family Decorative Arts Court through August 20.

Just one, in fact: Austria-born, Minneapolis-based Tina Blondell, who is thrilled to find her 1999 painting, I’ll Make You Shorter by a Head (Judith I), in such rarified company. Her work and the 13 others in the show all depict the same biblical event, with different approaches: the decapitation of a military leader at the blade of a young woman defending her people from imminent invasion.

Blondell is also the only woman artist. “I was thrilled to feature a work that treats the story of Judith from a female perspective,” says Rachel McGarry, Mia’s Elizabeth MacMillan Chair of European Art and Curator of European Paintings and Works on Paper, who organized the Caravaggio exhibition. “Blondell’s take is so refreshing and layered with meaning. Her title is just fantastic. It gives Judith agency. This woman is not a passive participant in a foretold tale, she is directing the events that unfold.”

Why did you choose Judith as a subject?

I started a series of work in the mid-’90s called Fallen Angels, exploring male interpretations of our stories—women’s stories. I love Caravaggio, I grew up loving him. But that particular painting of his, that Judith, that timid little frail thing, she can’t handle what she’s about to do. I just wanted to portray a woman who would set out to do it and do it. She had a plan and a mission, and she accomplished her mission.

My favorite Judith of all time was the [Artemisia] Gentileschi painting. It’s massive. The part where the sword is going through the neck, you can see her actual fingerprints manipulating the red pigment on the white sheets.

I spent years on this topic of gender inequality.

How do you think your Judith responds to Caravaggio’s?

Mine is a direct reflection of Judith I by [Gustav] Klimt. But it’s more broadly my reaction to all the Judiths by male artists, including Caravaggio’s. They were all men painting Judith: we’re either villains or damsels in distress. Just humans who can’t accomplish anything that a man can accomplish.

We had four centuries of men painting women—their favorite subjects of all—and letting their depictions define us. My Judith actually wanted to accomplish the job, and as she focused on it her eyes just got narrower and narrower.

Have you seen other Caravaggios?

In Rome, I made it a point to see every Caravaggio possible. Then all of a sudden there was a Caravaggio exhibit. I got to see almost everything by him in one place. He was considered the first modern painter. He was using actual people; he put a little halo on them and then they were a saint. He was a super-realist, down to the dirty feet of his subjects. I also made a point of flying to Amsterdam for the Rembrandt-Caravaggio exhibition, where this same painting was on display.

The fact that this painting is here at Mia blew my mind. I didn’t think many of them got out of Italy.

What’s it like to be the only woman artist and living artist featured in this exhibition?

To me, it’s huge. All the work in this exhibit is fabulous. But this is such a great platform for me because what I actually set out to do with my work—to contrast my work with men’s work of the same theme—is actually happening for me. My goal has been accomplished. Other people can go through and say, “See, this is a woman’s interpretation of Judith.”

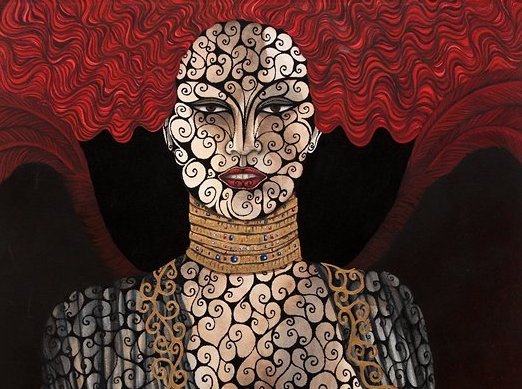

Why did you adorn Judith’s skin?

That’s a question everybody loves to ask. All my paintings that I began in 1994 and ended in 2005, all my watercolors, all have that on the skin. What it symbolizes to me is the accumulation of life experiences. Whatever we go through, whether it’s good, bad, all the experiences mark us, no matter what. No matter how hard we try not to hand it down to our kids. I started to think: What would we look like if we could see all that experience on our flesh? I begin to embellish after I finish the painting. It tells their story on their skin.

I chose the spiral for a specific reason. The spiral symbolizes the growth of a society or of consciousness. It’s a journey. All cultures have this patterning in their art.

Have you seen your work up in the gallery?

I went up there on the first day, by myself. I sat on a bench, and I watched people walk up to it, glance at it, then come back to it. It is interesting to see. It’s really in your face. I talked to one man, we talked about my piece and Caravaggio. I have a whole bunch of people who want me to take them to see the exhibit.

Once it comes down, it’s gone for an indefinite amount of time. I’m definitely going to see it again.

Can you explain your title?

The title is a direct quote from Queen Elizabeth. I’m sure she chopped a lot of heads off. She was an amazing woman. But I don’t think Judith and Elizabeth have much in common other than being powerful women.

Titles are really important to me. My titles are always a reflection of what’s going on. [Curator] Rachel [McGarry] knew it. She got it.