It wasn’t a promising call: “My stepfather liked to draw and I’m looking for a museum to house his work.” Rarely has Tom Rassieur, Mia’s John E. Andrus III Curator of Prints and Drawings, taken such a call and the artwork waiting at the other end of the line. Never, in fact.

Not until Jim Hogan drove to the museum from Hudson, Wisconsin, with a binder full of reproductions of his stepfather’s drawings, described by a Minneapolis newspaper in 1929 as “figures of his imagining, weird gnomes with gnarled hands and bent backs, fantastic creatures with a gentle twist of humor.” Hogan opened the binder and waited for Rassieur’s reaction.

Not until Jim Hogan drove to the museum from Hudson, Wisconsin, with a binder full of reproductions of his stepfather’s drawings, described by a Minneapolis newspaper in 1929 as “figures of his imagining, weird gnomes with gnarled hands and bent backs, fantastic creatures with a gentle twist of humor.” Hogan opened the binder and waited for Rassieur’s reaction.

He didn’t have to wait long. “From the first page, I was enchanted,” Rassieur says. “I’ve never encountered the works of an artist I haven’t heard of that were this wonderful.”

Several years later, Rassieur has staged an exhibition of the illustrations, now up in Mia’s Cargill Gallery: “Richard Holzschuh: Storybook.” And the Store at Mia is selling an activity book based on Holzschuh’s drawings. But the man behind them remains mysterious.

Several years later, Rassieur has staged an exhibition of the illustrations, now up in Mia’s Cargill Gallery: “Richard Holzschuh: Storybook.” And the Store at Mia is selling an activity book based on Holzschuh’s drawings. But the man behind them remains mysterious.

Richard Holzschuh was born in 1889, graduated from Central High School in Minneapolis, and studied at night at the Minneapolis School of Art, now the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, then affiliated with Mia. He spent two more years with the Art Students’ League of New York and briefly freelanced in commercial illustration.

And then he went to work—for Standard Oil, as an accountant.

Book illustration, of nursery rhymes and other fantastic tales, was his first and enduring love. But he figured he could never make ends meet that way. So he drew, painted, and made etchings after work at home, like any other hobbyist, except his talent and dedication were extraordinary.

“He continued to practice a very rigorous art,” Rassieur says. The Beard Gallery in Minneapolis gave him solo shows and Mia displayed his work in local artists’ exhibitions. And he did illustrate several children’s books.

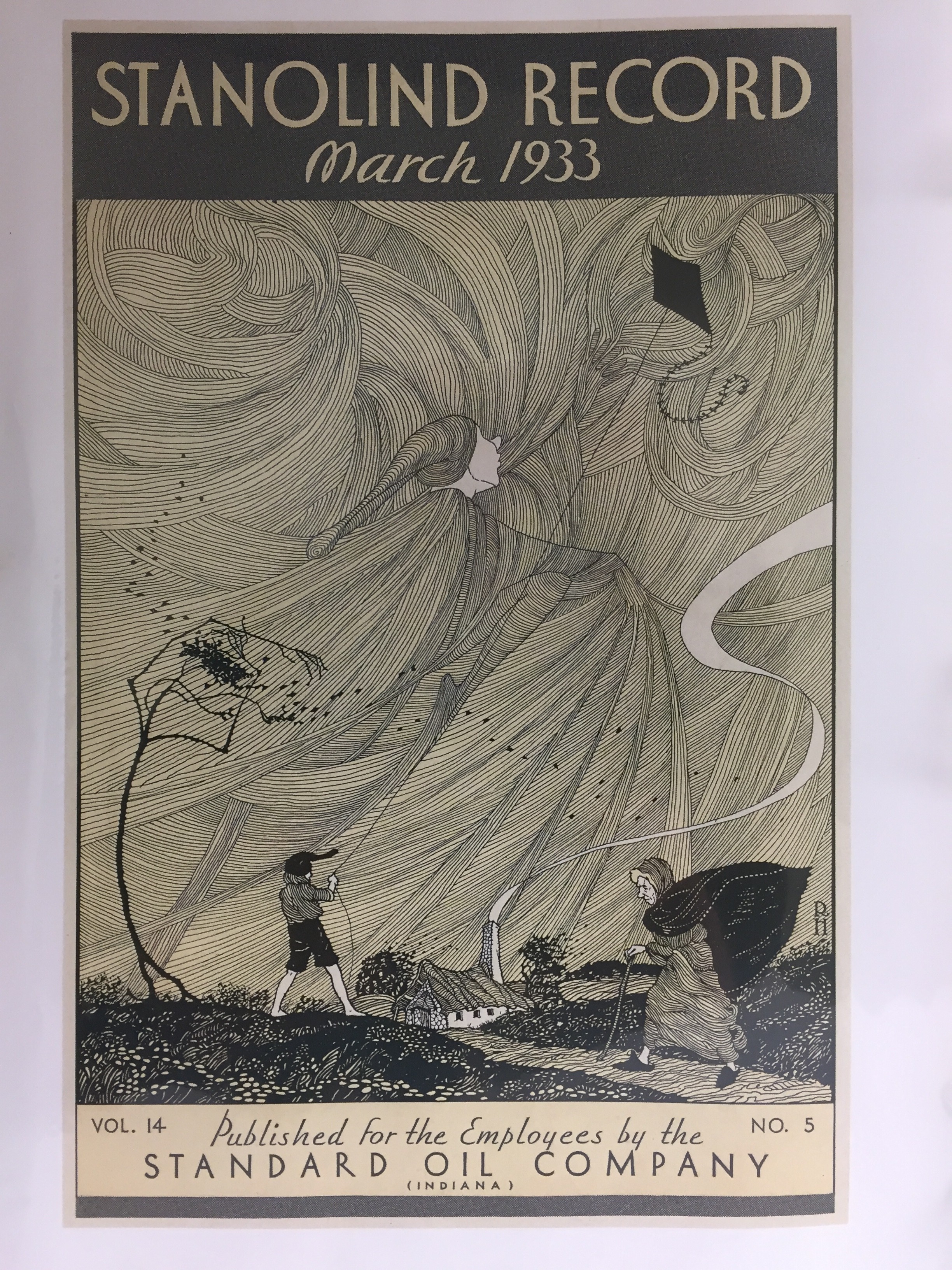

His work sometimes graced the cover of an employee magazine of Standard Oil, in which he was profiled. Holzschuh comes across as publicity-shy, a bit curmudgeonly—getting him to pose for the accompanying photo, the article notes, took a year of persuasion from a manager. Asked about his family, he said of his son, “Thank goodness he has no artistic inclinations.”

His work sometimes graced the cover of an employee magazine of Standard Oil, in which he was profiled. Holzschuh comes across as publicity-shy, a bit curmudgeonly—getting him to pose for the accompanying photo, the article notes, took a year of persuasion from a manager. Asked about his family, he said of his son, “Thank goodness he has no artistic inclinations.”

He may have regarded his talent as both a blessing and a curse, though he had no problem sharing it. He designed exquisite Christmas cards for family and friends. He taught etching classes. And he joined the Attic Club, a group of fairly bohemian artists who met in one loft-like space after another in downtown Minneapolis, critiqued each other’s art, and threw parties. Holzschuh served a few years as their treasurer.

His wistful figures, eluding the modern world in a land of thatched-roof cottages and load-bearing crones, were hardly cutting-edge in the 1920s and ’30s. Not that children’s literature was monolithic. In Mia’s ongoing International Modernism exhibition, El Lissitzky’s simple illustrations of red and black squares battling for supremacy were intended to comprise a children’s tale, a very different means to the same end as Holzschuh’s work: a sparking of the imagination.

His wistful figures, eluding the modern world in a land of thatched-roof cottages and load-bearing crones, were hardly cutting-edge in the 1920s and ’30s. Not that children’s literature was monolithic. In Mia’s ongoing International Modernism exhibition, El Lissitzky’s simple illustrations of red and black squares battling for supremacy were intended to comprise a children’s tale, a very different means to the same end as Holzschuh’s work: a sparking of the imagination.

When Holzschuh retired from Standard Oil in 1954, his coworkers wrote a poem in his honor. “In all the years that you’ve been with us,” reads one of the verses, “you were nice to have around. You never carried a chip on your shoulder but you always stood your ground.”