Exhibition Guide: José María Velasco: A View of Mexico

Introduction

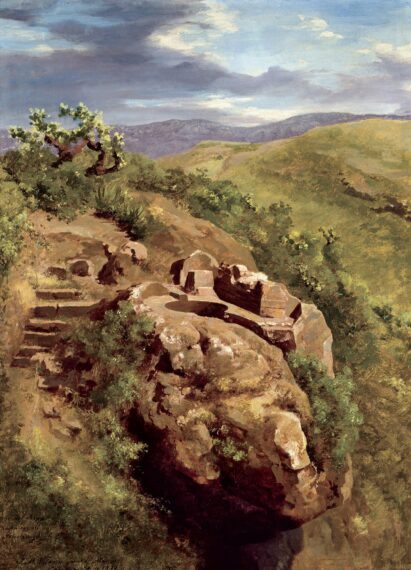

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. The Baths of Nezahualcóyotl, 1878. Oil on paper laid down on canvas. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City

José María Velasco always knew he would be an artist. He began to draw at age 12 and never looked back. He became the most important landscape painter in Mexico during the late 1800s. His early love of art led him to study with the Italian artist Eugenio Landesio (1810–1879) at the first art academy in the Americas, the Academia de San Carlos, in Mexico City. Because he sold shawls in his uncle’s shop during the day, the teenager took classes at night. Among the many lessons he learned at art school was the importance of accurately representing geographical features, plants,

architecture, and the sky in all its beauty. He also studied how to draw the human figure and animals. Throughout his life he passionately studied nature and painted the landscape of the country he loved.

Velasco loved to study nature. In the exhibition you will see detailed studies of local plants, including shrubs and cacti, that he made in preparation for his larger paintings, as well as other works, such as The Forest of Pacho (Jalapa), in which the plants are the main subjects. The unique geological features of Mexico City and other important sites in his country also captivated Velasco’s attention. Whether ancient volcanoes or simply large, interesting rocks, geology features heavily in his landscapes. The way he captured in paint the subtle and varied colors and bold textures of these subjects testifies to the importance he placed on closely observing and celebrating the wonders of the natural world.

But Velasco’s interests didn’t end there. He was dedicated to learning about Mexico’s history and including allusions to both its past and its present in his paintings. You will notice how he references history through the inclusion of details—from very ancient pyramids and a Christian basilica from Mexico’s colonial period to modern railroads and symbolic images that connect past to present—in order to emphasize Mexico’s rich and complex history. Though passionately committed to observing nature, Velasco also loved to construct his images by putting together ideas from different times and places, imbuing the landscapes with deep meaning.

José María Velasco spent his life making art and teaching. He painted up until his death, in 1912. The exhibition includes selections of small paintings on postcards that show how he adapted a looser painting style late in life. Be sure to look for a small painting of clouds on which the bottom remains unfinished, leading historians to conclude that he began it in the morning on the very day he died.

This exhibition guide highlights a selection of Velasco’s paintings featured in “José María Velasco: A View of Mexico.” We have included discussion prompts and activities to encourage visitors of all ages to look closely at the paintings and think about some of the ideas that were so important to Velasco and his art. Whether you are discussing these paintings in your classroom, home, or in the galleries, we encourage you to have pencil and paper on hand to participate in some drawing activities as ways to apply some of Velasco’s lessons, or simply to sketch whatever grabs your attention in these fabulous paintings.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. Study of Clouds (Ultima tarjeta postal), 1912, oil on card. Museo Kaluz, Mexico City

Artworks

Two Paintings Titled The Goatherd of San Angel

These two paintings titled The Goatherd of San Angel showcase Velasco’s interest as a student in juxtaposing the rhythms of nature with the advances of industrialization in the Valley of Mexico. He made the small study of 1861, below, out in nature at the site of the factory of La Hormiga, one of Mexico’s first and most important textile mills. He further developed the theme in the larger painting, second below, made in his studio two years later. The composition in both works shows the factory on the right. On the left, a shepherd seems to save the herd from falling. In the center, a cascade of water pours from the dam that harnessed the flow of the Magdalena River in order to generate electricity and run the cotton mill.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. The Goatherd of San Ángel, 1861. Oil on canvas. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City.

Look and Discuss

Look at the two paintings. In what ways are they the same? In what ways do they differ? The smaller painting was made as a study, outside in nature. The later one was painted with the goal of telling a story. What story is being told? What’s going on in the painting?

Try your hand at drawing or painting in nature! When you have time, go outside and create a study or sketch of some part of your environment that you find interesting. In a couple of days look at your study and think about the story you would like to tell in a second artwork based on your study. Then, make a second artwork with three to four details that tell that story. Think about people, plants, animals, and other features that will make your story interesting.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. The Goatherd of San Ángel, 1863. Oil on canvas, Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City.

A Rustic Bridge in San Ángel (Puente rústico de San Ángel), 1862

This small oil painting shows Velasco’s early interest in representing the natural world, a lesson he learned from his teacher Eugenio Landesio. The subject is an aging alder tree in San Ángel, rooted in the muddy banks of a slow-moving stream. A crude bridge made of wooden planks lies across the tree’s lower boughs. This small painting made on site became the model for a larger version of the same theme in 1865. Notice how precisely Velasco showed the tree’s leaves and the lichen covering the branches. He continued to develop this approach to observing and recording nature, as evidenced by the botanical illustrations he made in the late 1860s.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. A Rustic Bridge in San Ángel (Puente rústico de San Ángel), 1862, oil on canvas. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City

Look and Discuss

What do you see? What are some of the details you notice in this small painting? What sounds might Velasco have heard when he was making this painting in nature?

What is human-made in this picture? Why do you think Velasco might have wanted to paint this old bridge?

Velasco was inspired by his art teacher to go outside to paint nature in great detail. What teacher has inspired you the most? In what way?

Try your hand at scientific drawing! Check out the “Drawing from Nature” activity in the Activities section of this guide.

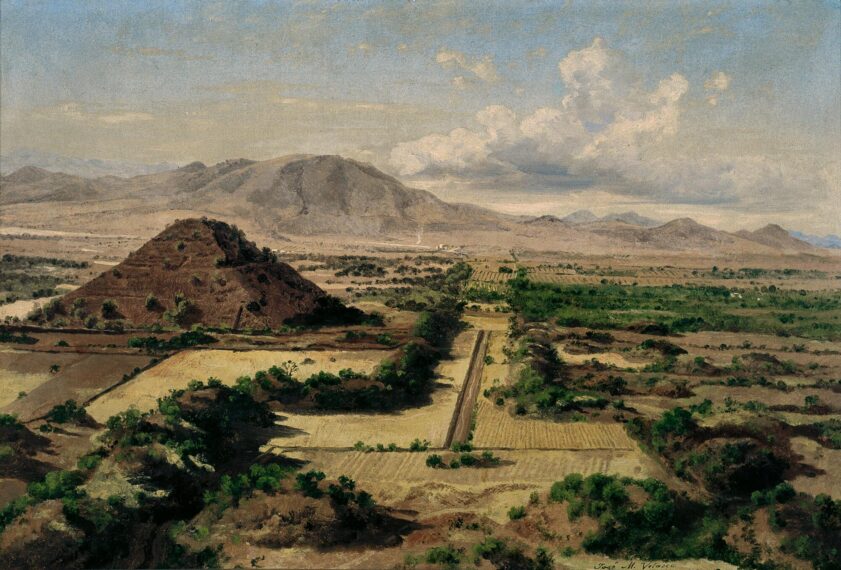

The Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacán (Pirámide del sol en Teotihuacán), 1878

This painting is one of two different views Velasco painted of the monumental temple complex of the ancient city of Teotihuacán, northeast of Mexico City. Built between 100 and 450 ce, the immense pyramids captured Velasco’s attention and imagination. When Velasco painted the pyramids on site he was on an archaeological expedition led by the director of the Museo Nacional.

In this scene Velasco showed the monumental Pyramid of the Sun. He positioned himself on top of the smaller Pyramid of the Moon to capture this particular view. The pyramid is aligned with the long road that formed the main north-south axis of the ancient city, called the Avenue of the Dead.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. The Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacán (Pirámide del sol en Teotihuacán)(detail), 1878. Oil on canvas. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL. EL2025.10.10

Look and Discuss

What do you see? What do you see in the foreground? The middle ground? The background? Notice how Velasco leads our eyes back from the front of the picture with the row of trees that stops near the pyramid. What does he do to move our eyes to the mountains farther away?

Velasco was interested in Mesoamerican history. He traveled and went on archeological expeditions to learn as much as possible. What is a topic that you would like to know more about? How might you go about learning more? What kinds of activity could you do to learn more about that topic?

Compare and contrast this painting with the smaller painting in the exhibition that depicts both pyramids. What do they have in common? How do they differ? Which one do you like more? Why?

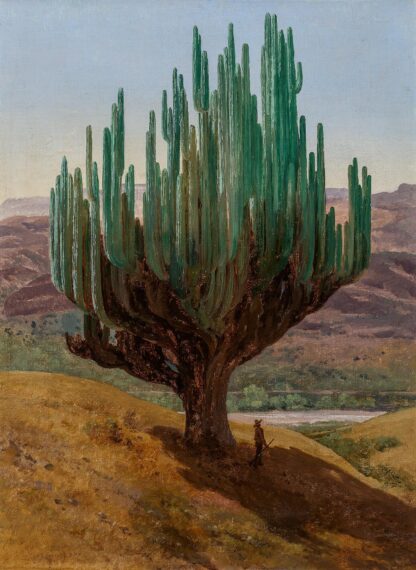

Cardón, State of Oaxaca (Cardón, Estado de Oaxaca), 1887

A giant Mexican cactus, cardón (Pachycereus weberi), dominates this painting. A man in a sombrero standing beneath it shows us just how immense the cactus is. Velasco visited the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca in December 1887 to complete a commission (special order) to paint a cathedral. While there he documented the flora and geological features and painted some landscape views. The loosely painted earth tones of the land around the large cactus capture the arid, rugged beauty of the village of Tecomavaca. The rich shades of green, most prominently seen in the cactus’s branches, shine against the blue sky.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. Cardón, State of Oaxaca (Cardón, Estado de Oaxaca) (detail), 1887, oil

on canvas. Museo Nacional de Arte,

INBAL, Mexico City

Look and Discuss

What do you see? How do you think it would feel to stand under the enormous cactus, like the man in the painting? What kind of climate or environment do you think this is? What are some of the clues that tell you about the climate?

What kinds of trees or plants would you include in a picture to say something about Minnesota and our climate? How would your picture look different depending on the season? Sketch some ideas at the end of this guide. Think about what kinds of details and colors you might include later.

Scale is an important element of this painting. Think about something that makes you feel very small. How might you show the size of that thing in an artwork? Then think about how big you look to an ant. Draw what you imagine you look like to that ant.

The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel (El Valle de México desde el Cerro de Santa Isabel), 1877

This very large painting is Velasco’s most important work, painted at the height of his artistic development. In it, he left behind the convention of including people in his landscape. Instead, he focused on the strong composition and important details that he observed and studied. The drama here is the powerful atmospheric effects of the sky and clouds.

Painted during the spring of 1877, Velasco expressly intended to have it exhibited in Paris at the Universal Exposition of 1878. He even arranged to have his painting transported at his own expense, to be displayed in the Spanish section of the fine arts pavilion, since Mexico was out of favor in Europe at the time. Before being sent to Paris, it was displayed at the National Academy in Mexico City, where it was awarded the gold medal.

Velasco carefully constructed this composition with apparently little concern for accuracy. He rearranged the view of the valley and borrowed elements from others of his own earlier paintings to structure this grand scene. The painting brings together three historical eras—the pre-Hispanic past, centuries of Spanish viceroys, and contemporary Mexico. In the background he included a view of Mexico City, the capital of the modern republic, connected to the rest of the nation by railways and avenues.

Closer to us in the center of the painting is a basilica dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe at the foot of the hill of Tepeyac. The Virgin is an important symbol of Mexico’s Mestizo identity, combining Spanish and Indigenous traditions.

In the foreground of the painting, Velasco depicted a nopal cactus and an eagle with a bird in its mouth, both referring to the mythical establishment of Tenochtitlan, capital of the Mexica people in the 1300s. Both the eagle and the nopal cactus were adopted as symbols in the nation’s seal, which also appears in the center of the Mexican flag. The painting was so successful that Velasco was commissioned to do seven versions of it.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel (El Valle de México desde el Cerro de Santa Isabel), 1877, oil on canvas. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City

Look and Discuss

What do you see in this grand painting? Look for three important elements included by Velasco as references to his country’s past and present. In the foreground find an eagle and a nopal cactus, symbols of the Mexica (Aztecs). Now look in the middle of the painting to find the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a symbol of the commingling of Indigenous and Spanish traditions, so important to Mexican identity for many. In the background, locate Mexico City, the modern capital of the republic.

Velasco combined his observations of these various elements to invent this seemingly real view of his beloved country. Think about what elements of your environment, history, and community you would include in a composition to tell a story that is important to you—real or imaginary.

Visit the Activities section of this exhibition guide for a drawing activity focused on symbols.

Eruption (Erupción), 1910

Late in life, Velasco painted this dramatic volcanic eruption from his imagination. Although he had made two earlier prints illustrating volcanic eruptions, one based on a written description and the other drawn during an actual eruption in the state of Nayarit, this work heightens the drama of this natural phenomenon. This painting and other small works exploring astronomical phenomena, nocturnal scenes, and special atmospheric effects attest to Velasco’s commitment to experimentation during the final decade of his life. He explored new subjects and styles as he grappled with representing the most uncontrollable forces of nature.

By providing minimal context for the surroundings, Velasco heightened the intensity of this volcanic eruption. The lava in the very foreground, rendered in thick layers of red and yellow paint, violently explodes. In contrast, the billowing column of dark smoke above that takes up much of the painting is applied with loose, quick brushstrokes. Overall, the impact of this late painting contrasts starkly with the more finished and tranquil landscapes for which he is best known.

José María Velasco. Eruption, 1910. Oil on card, 14 × 9 cm. Museo Nacional de Arte, INBAL, Mexico City. © Reproducción autorizada por el Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura. Photo: Francisco Kochen. X12278.

Look and Discuss

What do you see? Describe the volcanic eruption. What makes this picture so dramatic?

Velasco loved science and regularly documented his experiences of natural phenomena. Why do you suppose he chose later in life to draw on his imagination instead? What kind of science do you like? What do you like to study in nature? Think of a science or nature experience that you would like to share with others in a work of art. Using sketch pages at the end of this guide, draw it now or make a sketch to save for later. Will you aim for factual description or dramatic impact?

Activities

Create a Scientific Drawing from Nature—Inspired by José María Velasco

José María Velasco was not only a master of landscape painting but also a careful observer of nature. Much of his sketching and painting took place outdoors, where he could study his subjects closely. His landscapes are known for their remarkable attention to detail—so precise that plants and trees can often be identified by species. In addition to sweeping views of the natural world, Velasco also created botanical drawings: scientific illustrations that highlight the physical characteristics of plants and sometimes include animals and information about their habitats.

In this activity, you can take on the role of scientific illustrator—just like Velasco.

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. Mafaffa Leaves (Hojas de Mafaffa), c. 1880, oil on paper. Museo Kaluz, Mexico City

Instructions

1. Go outside or use natural specimens and choose a nearby outdoor space like a garden, schoolyard, or park, or bring natural specimens (leaves, branches, flowers, etc.) into the classroom for observation.

2. Observe closely: Take time to observe the plant or natural object in detail. Look at shape, texture, and color, and how different parts connect. Use a magnifying glass if available.

3. Sketch what you see: On the next page, create a detailed pencil sketch of your chosen plant or object. Include as much detail as possible—think about Velasco’s precision.

4. Label scientific features: Identify and label parts of the plant (such as stem, leaf, flower, seed, etc.). Add notes about color, size, and texture, and any other observations.

5. Add habitat information: On a separate part of the page or the back, write a few sentences about where this plant is found, what kind of environment it grows in, and any animals that interact with it.

6. Optional: Add color: Use watercolor, colored pencils, or ink to enhance your drawing, keeping the focus on accuracy.

Symbols in the Landscape

In José María Velasco’s painting The Valley of Mexico from the Hill of Santa Isabel, the artist included important symbols of Mexico in the landscape. These symbols, like the nopal cactus and the eagle, connect to the ancient story of the founding of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Mexica people in the 1300s.

In this myth, the eagle is often shown with a snake in its mouth, but it was also known to collect feathers from other birds to build its nest. These images are powerful symbols that many people in Mexico recognize as part of their history and identity.

In this activity, you will create your own landscape or scene that includes symbols from your life, culture, or imagination to tell a story that’s meaningful to you.

Instructions

1. Think of symbols: What things are important to you, your family, or your friends? Think about special objects, places, or traditions.

2. Think about your story: What story do you want to tell? It can be real or imaginary.

3. Plan your drawing: Choose a few symbols to include. Think about where each one will go. Will anything be in front of or behind something else?

4. Start sketching: Use a pencil to draw your scene. Add your symbols and connect them in your picture.

5. Optional: Add color: Use watercolor, colored pencils, or ink to enhance your drawing, keeping the focus on accuracy.

Word Search Puzzle

Seek and Find

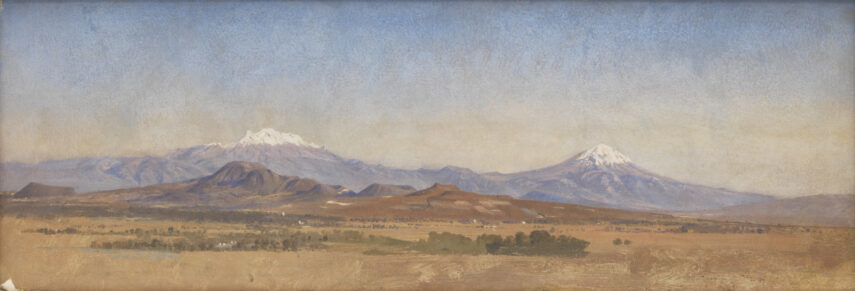

José María Velasco, Mexican, 1840–1912. Valley of Mexico (Valle de México), 1875, oil on canvas. Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, New York

José María Velasco’s paintings illustrate his interests in science and history. As you go through the exhibition, look for these things:

Find these geological features:

• Huge rocks

• Volcanoes

• Mountains

Find these historical structures:

• Pyramids of the Sun and Moon

• Castle of Chapultepec

• The Baths of Nezahualcóyotl

Find these natural phenomena:

• Rainbow

• Comet

• Volcanic eruption

Find these plants:

• Agave plant (a succulent with long, pointy leaves)

• Ferns

• Cactus