Teachers Guide: Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room

Introduction

In his foreword to a book about Alice S. Kandell’s collection of Tibetan cultural resources, Tibet’s spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, wrote of the importance of preserving and promoting Tibetan culture. He also expressed hope that the book about this collection would provide readers with a deeper appreciation of the richness and refinement of Tibetan culture and would inspire efforts to save it from disappearing forever. (Marylin Rhie and Robert Thurman, A Shrine for Tibet: The Alice S. Kandell Collection of Tibetan Sacred Art, Overlook Press, 2010)

The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room at Mia invites museum visitors to learn about Tibetan culture by bringing together some 200 cultural resources (artworks) as they might have looked if assembled in a Tibetan Buddhist home shrine. Many of the artworks represent teachers (lamas and gurus), buddhas, deities, and protectors, all of whom possess qualities that Buddhists seek to acquire in their pursuit of freedom from the suffering that they believe characterizes the daily lives of all beings.

We invite you to learn about the uniqueness of Tibetan practices and art forms by studying a few of the devotional works featured in Mia’s Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room. You’ll find discussion prompts throughout the guide to encourage students to look closely, describe what they see, and think about how the desired qualities expressed in the objects relate to their own lives. Other prompts encourage students to think about key ideas that connect to select state standards.

Minnesota State Standards in Social Studies

Consider connecting classroom study and an in-person experience of the Shrine Room to several of the Minnesota state standards in history, ethnic studies, and geography, depending on the grades you teach.

History

- • Change, Continuity, and Context: Ask historical questions about context, change, and continuity in order to identify and analyze dominant and nondominant narratives about the past.

- • Historical Perspectives: Identify diverse points of view and describe how one’s frame of reference influences historical perspective.

- • Historical Sources and Evidence: Investigate a variety of historical sources by a) analyzing primary and secondary sources, b) identifying perspectives and narratives that are absent from the available sources, and c) interpreting the historical context,

intended audience, purpose, and author’s point of view of these sources.

Ethnic Studies

- • Identity: Analyze the ways power and language construct the social identities of race, religion, geography, ethnicity, and gender. Apply these understandings to one’s own social identities and those of other groups living in Minnesota, centering those whose stories and histories have been marginalized, erased, or ignored.

- • Resistance: Describe how individuals and communities have fought for freedom and liberation against systemic and coordinated exercises of power locally and globally. Identify strategies or times that have resulted in lasting change. Organize with others

to engage in activities that could further the rights and dignity of all. - • Ways of Knowing/Methodologies: Use ethnic and Indigenous studies methods and sources in order to understand the roots of contemporary systems of oppression and apply lessons from the past in order to eliminate historical and contemporary injustices.

Geography

- • Places and Regions: Describe places and regions, explaining how they are influenced by power structures.

- • Human Systems: Analyze patterns of movement and interconnectedness within and between cultural, economic, and political systems on a local to global scale.

- • Culture: Investigate how sense of place is impacted by different cultural perspectives.

- • Causation and Argumentation: Integrate evidence from multiple historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument or compelling narrative about the past.

Spotlight on Tibet

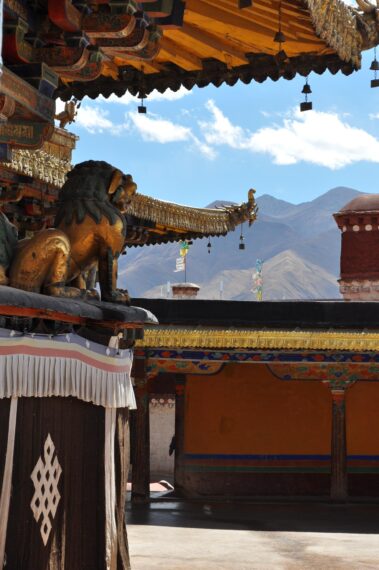

View from Jokhang Temple Monastery, Lhasa, Tibet

Tibet, located in South Asia in the Himalayas, is home to some of the world’s tallest mountains.

Most of Tibet is within an area of land called the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, which sits about 15,000 feet above sea level. The Himalayas are south of the plateau. The famous Mount Everest, the world’s highest peak, is on the border between Tibet and Nepal.

Diverse groups of people live on and around the plateau. Although they are culturally and linguistically diverse (Tibetans speak their own language, Tibetan), they are connected by political ties and centuries of trade across the Himalayas. These same trade networks contributed to the expansion of Tibetan Buddhism. Tibet’s economy is largely based on farming. Tibetans raise yaks, horses, cows, sheep, and goats and grow a wide variety of grains and potatoes. The Dalai and the Panchen lamas are the main leaders of Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibet became a powerful and independent Buddhist kingdom between the 600s and 800s CE. In the 1200s the Mongols took over rulership. In the 1700s, China’s Qing dynasty ruled Tibet. When the Qing lost power in 1912, local leaders took charge. In 1950, the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, became the head of Tibet’s government. But in 1950–51, the People’s Republic of China claimed control over Tibet, which ultimately led to a rebellion by Tibetans in 1959. The Dalai Lama fled to India to continue ruling Tibet from afar. In 1965 China declared Tibet an autonomous region of China.

Today the Dalai Lama promotes peace around the world and speaks about the Tibetans’ desire for independence. In 1989 he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his commitment to nonviolence in his efforts to end Chinese control of Tibet.

Tibetans in Minnesota

Many Tibetans left their homeland to live in exile in Nepal and especially in India, where the 14th Dalai Lama fled in 1959 to continue to lead Tibet. Today, other large Tibetan communities make their home in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, France, Taiwan, and Australia.

Tibetans began arriving in Minnesota in 1992–93 as part of a larger U.S. Congress–led Tibetan resettlement project. Through immigration visas granted by Congress, 160 Tibetans living in exile in Nepal and India were resettled in the Twin Cities area. Over the past 30 years, with family reunification and relocation, Tibetans continued to move to our state.

Today, Minnesota is home to about 5,000 Tibetans, second only to New York State.

Discussion

- • What is the power imbalance represented by this summary of the last 75 years of Tibetan experience? What can be learned from this story?

- • Research the history of Tibet’s relationship to China by looking at multiple sources or accounts. Identify different perspectives that you encounter.

- • Research the story of Tibetans’ migration to Minnesota over the past 30 years. Consider what kinds of primary sources could help you learn about their immigrant experiences.

Performance by dancers from the Tibetan American Foundation of Minnesota at Mia, September 2024

Tibetan Buddhism

“Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room: The Alice S. Kandell Collection,” exhibition view

In the 5th century BCE, the historical Buddha taught a path to overcoming sorrow and suffering. His teachings, which spread throughout Asia, laid the foundation for many forms of Buddhism. Tibet developed its unique form of Buddhism in the eighth century, Vajrayana Buddhism. Central to this Vajrayana school of Buddhism, is the idea that through rituals, a practitioner’s path to enlightenment—or freedom from self-centeredness and suffering (Buddhahood)—can be attained in their lifetime. It incorporates a strong focus on the role of teachers, study, monasticism, and ritual practice.

Daily rituals including offerings to specific teachers and deities are central to the belief system, which emphasizes the possibility of attaining enlightenment in one’s lifetime. The primary focus of this practice is compassion for others. If one performs actions solely to benefit oneself, the practices are ineffective. Tibetan Buddhism is practiced today from northern India across the Himalayan region, into the western parts of China, and in diasporic communities around the world.

Tibetan monks from the Gyuto Tantric University constructing the Yamantaka Mandala at Mia, 1991

Tibetan nuns from the Jangchub Choeling Nunnery creating the Green Tārā Sand Mandala at Mia, 2024

Tibetan Buddhism: Teachers

Tibet, Sixth Dalai Lama, 18th century, gilt copper alloy with pigment. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.32a,b

A distinguishing feature of Tibetan Buddhism is the central role it gives to teachers. There are many kinds of teachers, from the “good friend,” who models generosity and wisdom, to the mentor or guru, who instructs practitioners in the path of tantras (scriptures) and helps them see the possibility of their own enlightenment. Lama mentors are responsible for keeping the dharma (teachings) alive for Tibetans.

These lamas, gurus, and masters are already buddhas, and their presence reminds other devout Buddhists that the attainment of Buddhahood is possible for them as well. That idea is central to Tibetan Buddhism.

Monks and nuns provide important guidance and education in their communities, protecting and promoting Tibet’s language and culture. In Tibetan Buddhism, teachers’ roles are complex.

Ultimately, they all support the end goal of helping others to attain the knowledge and wisdom needed to free themselves from suffering.

Tibetan Buddhism: Shrines

Shrines are considered to be doorways into the realm of enlightened beings. They are a connection between the world of the sacred and extraordinary and the world of the ordinary. Through ritual practice, beings can evolve from self-centeredness and suffering to enlightenment.

Hence, many Tibetan Buddhist homes feature a shrine room. These spaces are the locus of important rituals of daily life, including the making of offerings.

Shrines come in many shapes and sizes, from humble mountain caves to lavish monastic temples. What these spaces have in common is the inclusion of sacred objects such as sculptures and paintings of buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other enlightened beings upon whom people meditate and to whom they make offerings.

The deities in Tibetan Buddhism are not gods in the more common sense of the term. Many are buddhas, who, through meditation, study, and ritual, have transcended the ordinary. Others are bodhisattvas and their wrathful manifestations—protectors of the faith—and a variety of semidivine supernatural beings.

When Tibetan Buddhists chant a mantra (prayer) associated with a specific Buddha or other enlightened being, they are not just asking for blessings or help, they are making progress toward the goal of becoming buddhas (“awakened ones”) themselves.

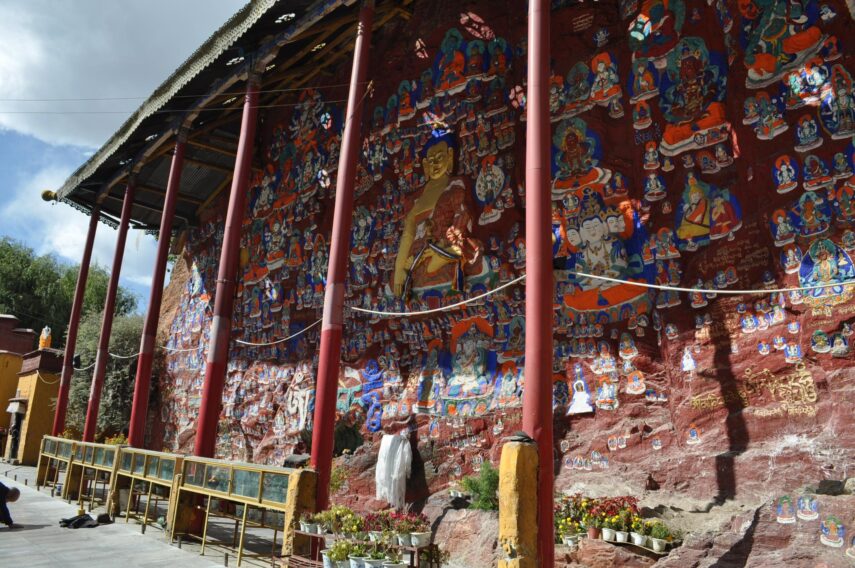

Rock carvings, Chakpori Hill, Lhasa, Tibet

Tibetan Buddhism: Offerings

Why make offerings? Tibetan practitioners make daily offerings within shrines as a way to express devotion and accrue merit. Making offerings to images of the buddhas, bodhisattvas, deities, and teachers is a way to ask for blessings and assistance with concerns both worldly and spiritual.

These offerings are fundamental to the multisensory experience of a shrine. Glowing butter lamps, fragrant incense, white silk scarves, music, foods, flowers, and saffron-infused water contribute to the experience. Butter lamps (the “dharma light”) are a means of offering light to enlightened beings.

“Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room: The Alice S. Kandell Collection,” exhibition view

The Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room: The Alice S. Kandell Collection

The look and feel of this re-created Tibetan shrine room (mchod khang) are inspired by a type of space you might encounter in the home of a relatively affluent and devoted Tibetan Buddhist family. This is just one type of Buddhist shrine that exists in Tibet and beyond, as shrines range from humble mountain caves to lavish monastic temples. What these spaces have in common is the inclusion of sacred objects—such as sculptures and paintings of buddhas and other enlightened beings—that are meditated upon and venerated.

Most of the sculptures and paintings represent aspects of enlightenment, or freedom from desire and suffering, and serve as inspiration for Tibetan Buddhist practitioners. Tibetan Buddhists seek to acquire the important qualities of the figures represented—including the Buddha, bodhisattvas (beings who put off Buddhahood to help others in their journeys), lamas (teachers), and fierce protector deities—in their own personal quests for enlightenment. Each object is a cultural resource that represents a history of the practitioners who used it and now serves the purpose of helping museum visitors better understand Tibet, its belief systems, and its art.

Gilt bronze sculptures, thangkas (paintings of spiritual realms), ritual implements, painted furniture, textiles (carpets, coverings, wall hangings, and canopies), flickering light, and chanting communicate the importance of ritual, sacred role models, and teaching in this particular type of shrine room. They emphasize the multiple functions of the room as a space for making offerings, performing daily rituals, and contemplation.

The profusion of ritual objects, displayed on painted furniture and hung on the walls, creates a sense of abundance in keeping with a Tibetan vision of the sacred. It also suggests the devotion of generations of practitioners, each of whom creates or commissions precious objects as an act of faith, to accrue merit, or to commemorate an important event.

Alice Kandell designed the shrine room to be an immersive environment that engages all the senses, as it would in a home of Tibetan Buddhists. Practitioners would look at the vast array of images, recite mantras (prayers) to musical accompaniment, use prayer beads to keep track of mantras, anticipate the taste of foods, and experience the aroma of offerings, including butter lamps and incense.

On another level, practitioners create a shrine as a complete sensory experience for the beings represented in the artworks, with offerings that are pleasant to see, touch, taste, hear, and smell. For practicing Buddhists in Tibet, consciousness, or a sense of self in one’s mind, is itself a sixth sense. It’s important to engage one’s mind when interacting with the shrine.

The artworks in the shrine are arranged in keeping with Tibetan Buddhist traditions, without the identification labels one might expect to find in a museum setting. An image of the Buddha is placed at the center; offerings are placed at lower levels. The other artworks, including scroll paintings (thangkas), sculptures, ritual items, musical instruments, and ornamental textiles of brocaded silk that hang from the ceiling and pillars, occupy places in a composition dictated by tradition. Many of the cultural objects such as the vajras (thunderbolts) and bells, offering bowls, and pitchers are used in daily rituals and offerings. Handheld drums, trumpets made of conch shells, horns, and reed instruments also serve unique purposes.

Discussion

- • How might experiencing and talking about the Shrine Room contribute to your understanding of how different communities practice traditions?

- • How might you, as a class, use the Shrine Room as a resource for learning about Tibetan culture?

Sculptures: Buddha Shakyamuni

Tibet, Akshobhya (Shakyamuni), late 18th–early 19th century, gilt copper alloy with pigment, inset turquoise. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.57

Tibetan Buddhists believe in the existence of many buddhas, as well as in the potential for all people to become buddhas. They also believe in and follow the teachings (dharma) of the Buddha Shakyamuni, known as the historical Buddha, who is also considered to be the present Buddha.

Buddha Shakyamuni is recognizable in Tibetan sculptures by his monk’s robes. Shakyamuni’s hand gestures (mudras) also help identify him. The “calling the earth to witness” gesture signifies the moment he touched the earth with his right hand to witness his enlightenment—the moment when he finally understood that only when people stop wanting things and live a simple life, can they be happy.

Images of the Buddha show him looking blissful. They enable viewers to imagine the possibility of their own bliss. Viewers also seek to attain the wisdom of the Buddha, which teaches selflessness and openness.

They also seek the Buddha’s capacity for compassion, to feel for others wherever they are on their path.

Discussion

- • Describe the sculpture. What do you notice first? How would you describe his facial expression? How would you describe his posture and pose?

- • Think about the qualities of Buddha expressed in this sculpture. Why do you suppose Tibetan Buddhists would want to acquire Buddha’s qualities for themselves? Think about someone in your life whom you admire. Which of their qualities do you feel would make you a better person on some days or in certain situations?

Sculptures: Bodhisattva Maitreya

Tibet, Standing Byams Pa (Maitreya), late 19th century, gilt copper alloy with pigment and inset semiprecious stones. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.65

Maitreya is a very special bodhisattva who is also called the future Buddha. When Shakyamuni Buddha’s teachings (dharma) are forgotten, Maitreya will be born in this world to rediscover the same truths as Shakyamuni. Maitreya is very popular in Tibetan Buddhism.

Maitreya is frequently represented as a youth wearing jewels and a crown. He frequently holds a lotus flower and a ewer (pitcher or jug). Another attribute is the dome-shaped Buddhist architectural form known as a stupa, seen here as part of his crown.

Bodhisattvas have the capacity to help other beings in their daily lives because they put off their own enlightenment in order to help others get closer to theirs. They are generally kind and generous helpers.

Discussion

- • Think about why Tibetan Buddhists might have represented the figure of the future Buddha as a young person. Do you think this makes sense? If yes, why? If no, what do you wonder about the representation?

Sculptures: Green Tara

Tibet, Sgrol-ljang (Green Tara), late 19th century, gilt copper alloy with

pigment and inset semiprecious stones. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.66

The sculpture below represents Green Tara, a female Buddha. Tara is present to protect and help those on the Buddhist path. Laypeople and monastics revere her and engage with her in many forms. She appears as a bodhisattva, a Buddha, and a meditational deity.

She can appear in all of these forms because of her ability to intercede in both spiritual and worldly matters. Representations of Tara typically emphasize her nurturing qualities.

It’s worth noting that Tara committed to remaining in a female body, even as a Buddha, until all beings attain Buddhahood. She therefore also stands as a lesson in the possibility of enlightenment for everyone, regardless of gender.

Discussion

- • Describe Tara. How does this sculpture communicate her kindness? How has the artist made her look approachable? Why might kindness be an important quality for a protector?

- • Why do you think Tara’s commitment to the possibility of enlightenment for everyone is important? Think about role models in your community who promote the equal treatment of everyone. What qualities or traits do they possess?

Sculptures: Vajrapani

Tibet, Vajrapani, 19th century, brass, pigment, inset stones. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.86

Vajrapani, “holder of the thunderbolt,” is one of the three protective deities or bodhisattvas surrounding the Buddha. Vajrapani protects the Buddha and manifests the power of all the buddhas.

In Tibet, Vajrapani is represented in many different fierce forms. One of these is Vajrapani-Acharya. Here he appears in human form, with a third eye and wild, flame-like hair. He wears a crown of skulls, a necklace of snakes, and a waistband made of tiger skin, also with skulls. He holds a vajra (thunderbolt) in his raised right hand, a symbol of indestructability.

Vajrapani represents a type of protector deity referred to as wrathful. He bares his teeth and raises his eyebrows to show that he is fiercely dedicated to protecting dharma, the teachings of the Buddha. At the same time, he is also a benevolent guardian of the path to enlightenment for present and future generations.

Discussion

- • Describe this sculpture. How do you feel when you look at it? Why do you suppose Vajrapani came to be represented as mean or aggressive? What advantage might there be to having strong, even ferocious, guardian figures?

- • Think about guardian figures from across time and cultures that similarly look very fierce or aggressive. How are these qualities represented in guardians, real and imagined, today?

- • Vajrapani is dedicated to protecting the teachings of the Buddha and helping people on their paths to enlightenment. What cause, belief, or idea do you care about so deeply that you want to defend it? What characteristics or attributes might you use in a representation of a defender of that cause, belief, or idea?

Sculptures: Lama Tsongkhapa

Tibet, Lama Tsongkhapa, late 19th century, gilt copper alloy repoussé with pigment. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.72.1a-d

The philosopher and teacher Lama Tsongkhapa (1357–1419) is known by Tibetan Buddhists as Je Rinpoche, or “Precious Leader.” In this sculpture, his roles as scholar and teacher are highlighted.

Because he is said to possess profound wisdom akin to that of the bodhisattva of wisdom, Tsongkhapa is represented with the same attributes. These include a flaming sword and a scriptural text, each one held aloft by a lotus flower. His hands are in the teaching gesture, or mudra, and he wears the hat of the Geluk sect, which he founded. It is one of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

Sculptures: Disciples

Left: Tibet, Khedrup Je, disciple of Lama Tsongkhapa, late 19th

century, gilt copper alloy repoussé with pigment. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.72.3a-c. Right: Tibet, Gyaltsab Je, disciple of Lama Tsongkhapa, late

19th century, Gilt copper alloy repoussé with pigment. Promised gift

of Alice S. Kandell L2023.76.72.2a-c

The other two sculptures are two of Lama Tsongkhapa’s disciples Gyaltsab Je and Khedrup Je. Both helped to expand and develop the Geluk school.

Discussion

- • Look at the sculpture of Lama Tsongkhapa. How would you describe his expression? What attributes does he have? What do they tell us about this important philosopher and teacher?

- • Think about traditions in your community, or others, that also honor important leaders. What are some of these traditions? Why are certain individuals honored? What are some of the characteristics of the leaders who are valued? Which, if any, of these characteristics are represented in artworks?

Furniture

The furniture in Mia’s Shrine Room includes altars, offerings, folding tables, and cabinets. Tibetan Buddhists make special cabinets in which to display statues and to hold holy manuscripts. The display cabinets are also known as dharma displays, or chosam. Some are quite simple while others are ornate; some even resemble the shape of a temple.

Small Sculptures

Tibet, Wheel of the Law with Deer, 19th century, gilt brass.

Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.70.1-.3

Each item in the shrine room signifies some aspect of Tibetan Buddhism and its practice. For example, the dagger symbolizes cutting through ignorance, desire, and hatred, the root causes of suffering.

The wheel flanked by two deer references the Buddha’s first teaching at Deer Park after his enlightenment, when he is said to have “set the wheel in motion.”

The Buddha

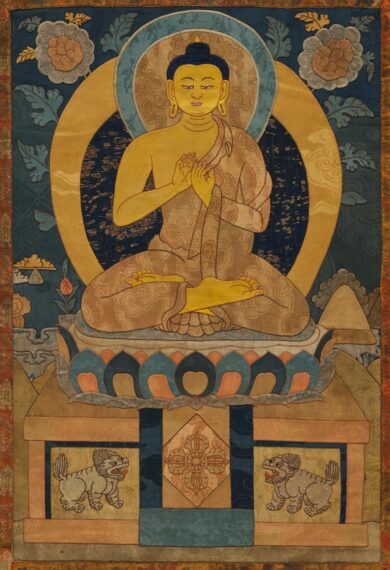

Tibet, Shakyamuni (Teaching Mudra), late 17th–early 18th century, appliquéd textile. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.91

The Buddha’s Story

This account of the Buddha’s story is written to be shared with young students as a read-aloud or handout.

Shakyamuni, better known later as the Buddha (“the Enlightened One”), was born in a grove of trees in Nepal about 2,500 years ago. His mother, Mahayama, called him Siddhartha, and he was part of the Gautama clan. A wise man (seer) named Asita predicted that Siddartha would become either a great king of the Shakya clan or a great teacher (Buddha Shakyamuni).

His parents wanted him to be a great king, so they kept him confined to the palace. Siddhartha sneaked out of the palace on three occasions, each time encountering something that deeply disturbed him: old age, sickness, and death. He wanted to understand why people needed to suffer, so he left home to study for six years with numerous teachers. Ultimately, none could answer his questions about why people suffer.

He then went to Bodh Gaya in India and sat under a banyan tree, determined not to get up until he understood for himself why people suffer. An evil being named Mara sent armies, storms, and temptations in efforts to distract him, but none of the distractions worked. On day 49 of his meditation, Siddhartha reached down with his right hand to touch the earth to witness his enlightenment—the moment he finally understood that only when people stop wanting things and live a simple life, can they be happy. At that moment he received the titles of Buddha (“the Enlightened One”) and Shakyamuni (“Sage of the Shakya Clan”).

Buddha, the teacher, traveled to Sarnath, near the Ganges River, to deliver his first lesson, “Turning the Wheel of Law.” He used the example of a wheel to teach people how to create a world in which everyone can move forward together. As long as no spoke is broken, the wheel can carry life’s burdens. Buddha continued to teach until he was 80 years old; he insisted that every human is a potential Buddha, and he aimed to end human suffering through his teachings. He was respected in his time and far beyond by people from all walks of life because he treated everyone with kindness and respect.

Discussion

- • Describe how Siddhartha Gautama worked to make things fairer for people at that time and identify the legacy (lasting impact) of that work today.

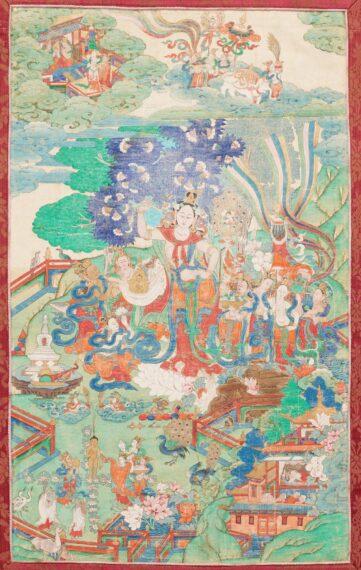

Tibet, Birth of Buddha and scenes from his life, 19th–20th century, pigments on cloth. Promised Gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.99

The Eightfold Path

Buddha laid out a path of eight basic understandings that he believed would make it possible for everyone to lead a good life. As you read them, think about which ones might be easiest for you and which ones might be most difficult.

- 1. Right understanding: People want things for themselves. Only when people follow the eightfold path, and understand it, can they know happiness.

- 2. Right aims: Love and help others. Don’t cheat or wish for things that others can’t have.

- 3. Right speech: Always tell the truth, but never with the intent of harming another person.

- 4. Right action: Never kill, steal, or be jealous. Do positive things that help others.

- 5. Proper work: Do work that won’t harm any living creature.

- 6. Positive thinking: Be positive.

- 7. Proper awareness: Never let your body control your mind. Know when to stop and when to say no.

- 8. Meditation: Train your mind to concentrate and think deeply so you’ll be able to learn to do many things.

Discussion

- • During Buddha’s lifetime, many people put forth solutions for ending human suffering. Some argued that each person should look out for their own well-being and forget about everyone else. What do you think would happen if each of us only looked out for our own interests? How do you look out for your own well-being? How do you look out for others?

- • Gautama Buddha was a teacher. He rejected the two extremes of wanting everything and giving up everything in favor of what is called “the middle path.” Why do you suppose he rejected the extremes?

- • Think about someone who is doing good work for their community and the resources that work takes (time, money, collaboration, etc.). Discuss what would happen to that person’s efforts if they gave up absolutely everything.

- • Think about a situation in your life or one that you have read about or seen on the news when self-centeredness and greed brought down a community. What was the situation? What happened in the end?

How to Recognize the Buddha in Art

Tibet, Akshobhya (Shakyamuni), late 18th–early 19th century, gilt copper alloy with pigment, inset turquoise. Promised gift of Alice S. Kandell, L2023.76.57

In this image of the Buddha from Mia’s Tibetan Buddhist Shrine Room, look for these characteristics of the Buddha, which are used in art throughout Asia and beyond:

- • The ushnisha is a bump or point on the Buddha’s head. It is a symbol of his wisdom and enlightenment.

- • The urna, a dot on his forehead, symbolizes wisdom. It is interpreted by some Buddhists as a third eye, or “the eye of consciousness.” It can also signify the Buddha’s lack of interest in earthly power.

- • Long earlobes remind viewers that Buddha was once a prince who wore great gold earrings but who no longer desires material things.

- • He wears the simple robes of a monk.

Discussion

- • Think about depictions of teachers in your culture. What are some characteristics that are regularly included in these representations? What do these features communicate? What representations of other leaders also include specific characteristics to ensure that people know who they are?