Art of the Ancient Americas

Lesson Objective

Students will see a diverse sampling of ancient art from the Americas and explore the ideas that influenced the design. Students will mold their own vessel, bowl, or pot and decorate the surface with design and images that are inspired by the natural world where they live.

Introduction

The art from across ancient Americas show some themes in common with each other though the people lived in varying landscapes. In this thematic section of Art in the Ancient Americas, you’ll learn about some core ideas that appear in ancient cultures and their art.

Warm-Up Questions

What features of the natural world are prominent where you live? Choose a landform and/or weather pattern you know well. Make a list so the class can view the different landforms, weather patterns, and environmental details that students share.

How does the natural world where you live impact your day-to-day decisions? Does it impact you in other ways? How?

Background

Use the art activity on this page alongside one (or all) of the ancient Americas themed sections. To learn more about each perspective, click on the idea of your choice. If you wish to add research and writing to your lesson, scroll down to Learning Extensions.

Core Ideas

- • Daily Life

- • Power and Hierarchy

- • Animals and the Spirit World

- • Nature’s Influence

- • European Contact

Art Activity

Guided Practice

What features of the natural world are prominent where you live? Choose a landform and/or weather pattern you know well.

Take a moment to look at a few of the art examples in each section, if you haven’t done so already. What do you see? What themes do you notice? Why might that be important? How does it compare to what your classmates came up with?

Let your natural world be the inspiration for an abstract pattern to decorate the surface of a mold. Sketch it, then share with a classmate what you designed and the significance behind the choice.

Materials

- • Clay or Model Magic

- • Toothpicks

- • Markers or paint

Procedure

- 1. Think about what you discussed above in the guided practice as a class. What are features of the natural world around you? What does your sketch resemble or symbolize?

- 2. Take the clay and mold what you want: bowl, vessel, pot, etc.

- 3. Once the molding is complete, take your sketch design and apply it to your mold. You can use a toothpick or other tools to engrave the texture and lines that you want.

- 4. Add color (marker or paint) if you wish!

- 5. Let it dry and display.

Reflection

What themes did you see in your class? What was similar or different about them? Why do you suppose those themes were significant? What was your biggest takeaway from the Art of the Ancient Americas section?

Learning Extensions

A Field Guide to Animals in the Americas | Research and Writing

Compile a field guide to animals of the Americas using the search tool on Mia’s website. Choose an animal from the collection and write a description of the animal based on its appearance in the work of art. Then research the animal and add a description of its behavior. What special characteristics of the animal might have made it special to the culture that created the work of art? Include your ideas in your field guide entry.

Ancient American Art Supplies | Research and Writing

The American continents include a wide variety of climates and terrain. Choose a region to investigate. What materials would have been available to an artist in that region 1,000 years ago? Consider plants, rocks and minerals, and animal parts. Which of those materials do you imagine would be easiest to work with? Which would you expect to survive over time?

Minnesota State Standards

Social Studies

3.3.17.1 Describe how different places, including school, the environment or local community, makes one feel.

4.3.17.1 Analyze how different perspectives have influenced decisions about where to locate and name places.

5.3.16.1 Describe how the choices people make have impacted a physical environment over time.

Visual Arts

5.0.4.7.1 – 5.9.4.7.1 Respond: Analyze and construct interpretations of artistic work.

5.0.5.9.1-5.5.5.9.1 Connect: Integrate knowledge and personal experiences while responding to, creating, and presenting artistic work.

Core Idea: Daily Life

Nasca artist, Peru, Double spout jar, 3rd century BCE–7th century CE, Polychromed earthenware. Gift of Mr. Austin J. Baillon, 77.59.6, null

Look at the pot. What do you see?

This pot from Mexico is in the shape of a pumpkin or squash, one of the staple crops of the ancient Americas. Its legs are in the shape of parrots, whose green and yellow feathers were prized because they are the color of healthy crops.

The ancient peoples of the Americas lived in landscapes as varied as the frozen tundra of the Arctic far north, the high mountains of South America, and the deserts and jungles in between.

Finding food was the first concern of the earliest groups of people. They were always on the move in search of the wild plants and animals they needed for survival.

The development of farming allowed people to produce and store extra food for times of the year when it was scarce. Not everyone in a community had to work to find food. Some people could devote themselves to other activities, like making pots or forming metal.

Many of the things these artisans made, such as seed pots and cooking utensils, were useful for daily life. Other objects played a part in rituals to ensure the good fortune of a community.

Since the community’s welfare depended upon a good crop, these ritual objects often refer to agriculture. Common images include corn, beans, and squash, the staple crops of the ancient Americas, as well as rainfall and water. These images appear in art made by the descendants of the ancient cultures to this day.

A more specific example would be the Nazca [NAHZ-ka] people of Peru. They lived in the driest desert in the world, so they relied on fish from the Pacific Ocean for their survival.

Left: Ancestral Pueblo artist, United States (Southwest). Pot (Olla), c. 1000–1300. Clay, pigments. The Putnam Dana McMillan Fund. 90.106. Center: Metate, 1–499. Costa Rica. Volcanic rock. Gift of Harold and Rada Fredrikson. 97.92.5. This stone metate [meh-TAH-tay], a tool for grinding corn, from Costa Rica was used only in rituals, not in daily life. It symbolized the chief’s control over the community’s food supply. Right: Colima artist, Mexico. Vessel, c. 300 BCE–200 CE. Clay. Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton. 92.85.20

Core Idea: Power and Hierarchy

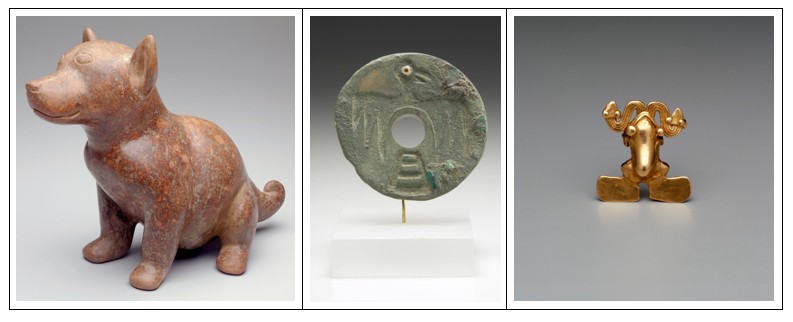

Chimú artist, South American, central Andes region. Ear Spool, c. 1150–1450. Gold alloy. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund. 43.4.1

This ear spool belonged to a Chimu [CHEE-moo] king of ancient Peru. Kings were buried with their jewelry for use in the afterlife.

Some people of the ancient Americas lived in large cities ruled by kings. Other cultural groups lived in small villages led by chiefs. In both cases, the elite of a society used art to show their power.

In large cities, such as Teotihuacan (TAY-o-tee-wa-KAHN) in ancient Mexico, art decorated the king’s court and other official buildings. Sculptures and rich materials also appeared in areas for performing rituals to protect the king’s power.

Smaller communities did not have the elaborate buildings of the large cities. But leaders of both large and small communities used art in the form of jewelry, costumes, and headdresses to show their power. Not surprisingly, rare materials like jade and gold were popular symbols of status. Colorful feathers from South American jungles were commonly used in costumes, reaching even the southwestern United States through trade.

Communities also prized materials for their symbolic meanings. Jade, green like growing ears of corn, was a symbol of fertility for some Central Americans. Gold suggested the power of the sun.

Left: Moche artist, Peru. Vessel. Clay, pigments. The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund. 44.3.43. A high-ranking official of the Moche [MO-chay] in Peru like the one pictured on this jar would have worn jewelry on his ears, wrists, and hat. Center: Spiro Mississippian artist, United States (Oklahoma). Gorget, c. 1200–1350. Shell. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund. 91.37.1. Men of high rank in the Mississippian culture of the eastern United States also wore discs on their ears. This image of the sun, about the size of the palm of a hand, was carved from limestone. Left: Warrior Figure, 100 BCE–500 CE. México (Jalisco). Ceramic. The John R. Van Derlip Fund. 47.2.24. Jalisco [ha-LEES-ko] warriors of West Mexico wore helmets topped by horns. This warrior’s helmet is decorated with two dogs instead, known to be good guides in the underworld. The sculpture probably represents a spiritual warrior created to stand guard at a tomb.

Core Idea: Animals and the Spirit World

Maya artist, Mesoamerica. Mask, c. 250–600. Stone. The Putnam Dana McMillan Fund. 99.3.1

Frogs cross between land and water. Many cultures believed they helped the dead cross to the next world. The power of animals to do things that humans can’t fascinated people in all regions of the ancient Americas. Owls can see in the dark to hunt at night, monkeys swing among the treetops, and bears sleep all winter. These special abilities seemed magical.

Animals that can cross between the land, air, and water were thought to be able to carry messages to the powerful spirit world. Ducks, for example, can fly great distances and dive deep into the water. Frogs change from young tadpoles living in water to adult frogs that can live on land. Images of these animals often appear on ritual objects to help priests or shamans communicate with the spirit world.

Other animals were important because they were particularly quick, strong, or fierce. Rulers, hunters, and warriors used images of animals like the jaguar and eagle to remind the people around them that they had similar qualities.

The jaguar is the largest predator of the Americas. Rulers from Mexico to the Andes of South America used it as a symbol of their power. The Maya of Mexico regarded the jaguar as a god.

Colima artist, Mexico. Dog, c.100–300 CE. Clay. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. John R. Kennedy. 99.57.3. Dogs were a symbol of wealth in ancient Mexico because they were raised as food for special feasts. They were also thought to help guide the dead in the afterlife. Center:

Spiro Mississippian artist, United States (Oklahoma). Ear Spool, c. 1200–1350. Limestone, copper, shell. The Robert C. Winton Fund. 2001.28.1. Hunters and warriors admired the speed, strength, and vision of birds of prey. A falcon decorates this ear spool found in Spiro, Oklahoma. Right: Diquis artist, Costa Rica. Pendant. Gold. Gift of Mrs. Arthur Bliss Lane in memory of her husband, Mr. Arthur B. Lane. 63.62.4

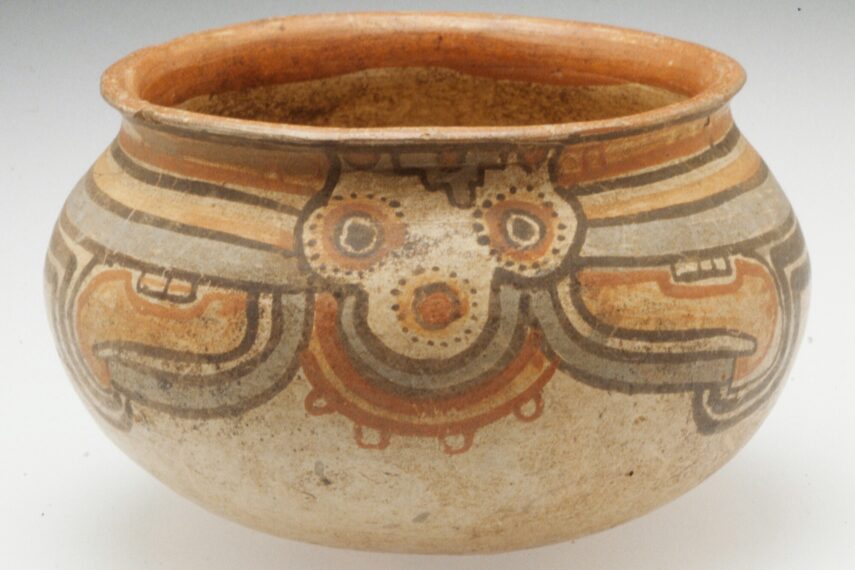

Core Idea: Nature’s Influence

Nicoya artist, Costa Rica. Bowl. Earthenware, pigment. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John I. May. 85.127.1

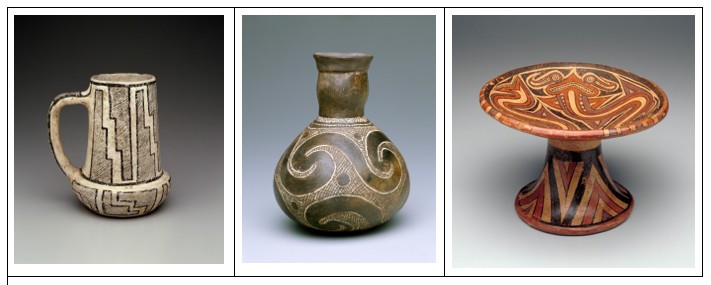

The zigzags and step shapes of the above pot refer to lightning and storm clouds. The ancient Puebloan people of the American Southwest eagerly awaited the rain brought by storms.

Much of the art of the ancient Americas is easy to recognize as a human figure or a particular animal. The decorations on some objects, however, seem at first glance to be nothing more than abstract patterns. That is, they do not resemble the world we see around us.

Many of these patterns are in fact inspired by nature. Sometimes an important detail helps us understand what the pattern represents. For example, large round eyes identify the shapes on the pot as an owl. In other cases, we can understand the pattern’s connection to the natural world by learning more about the people who made the object.

For example, the ancient Puebloan (or Anasazi [ah-nah-SAH-zee]) people lived in the dry American Southwest. The three-step shape commonly found in their art represented the tall thunder clouds that brought needed rain, as seen in the pot below.

Different cultural groups developed unique styles of abstraction. Today those different styles help archeologists identify who made the objects they study.

Left: Ancestral Pueblo artist, United States (Southwest). Vessel, c. 1050–1125. Ceramic, pigment. The Putnam Dana McMillan Fund. 90.105. Center: Caddo Mississippian artist, United States. Bottle, c. 1250–1499. Earthenware, pigments. The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund. 90.2.5. The spiral shapes commonly used by the Caddo of the southern United States suggest gently flowing water, a reminder of the many rivers and streams found in that area. Right: Gran Coclé artist, Venado Beach, Panama. Pedestal Plate, c. 800–1100. Ceramic, pigment. The Tess E. Armstrong Fund. 2002.58.1. The patterns on this plate combine features of snakes, lizards, fish, and birds. All these animals, common in tropical Panama, have qualities the maker of this plate found magical.

Core Idea: European Contact

Ngäbe (Guaymí) artist, Panama. Pendant, 8th–15th century. Gold. The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund. 53.2.8

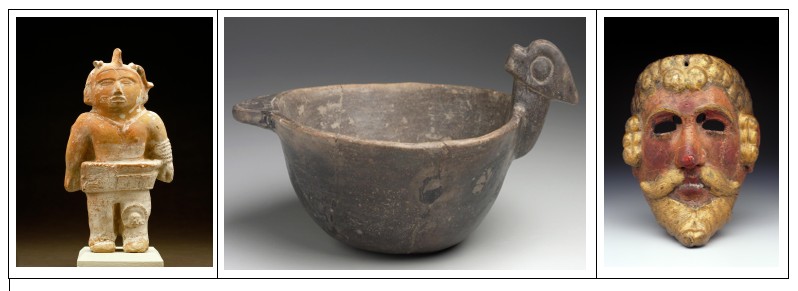

In North America, European settlers pushed native people off their traditional land. The descendants of the makers of this bowl in the shape of a waterfowl might now live in the dry southern plains instead of the Mississippi River valley.

This ceramic figure from Mexico is dressed as a ballplayer. The ballgame was an important ritual throughout the Americas. The Spanish banned the game in the Americas, but borrowed the idea for their own games.

The great lands and peoples of the Americas were unknown to Europeans until 1492. Likewise, Native civilizations thrived for thousands of years before they encountered Europeans. Contact between the two groups of people brought changes for both.

Some changes were brutal. Spanish conquistadors ruthlessly killed for gold and silver in Central and South America. European settlers in North America hungered for land. Diseases new to the Americas killed whole villages of people.

Other changes were more benign. The Spanish introduced horses and sheep to the Americas, which became important to native traditions. Europeans eagerly adopted American foods such as beans, corn, and chocolate.

Still other changes were the result of different ways of understanding the world. The ballgame, for example, was an important ritual for cultures throughout the Americas. It was much more than a game, sometimes ending in death. Spanish governors saw it as a pagan ritual and would not allow it to be played in the Americas. But they borrowed the idea themselves, and it was the source of popular modern ballgames.

Spanish conquistadors did not view the gold items they encountered in the Americas as sacred images. They sent thousands of tons of gold and silver to the Spanish treasury to be melted down for other purposes.

Left: Nopiloa artist, Mexico (Veracruz). Figure, c. 600–750 CE. Clay, pigments. The John R. Van Derlip Fund. 47.2.9. Center: Caddo Mississippian artist, United States. Bowl, c. 1100–1500. Earthenware. The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund. 90.2.3. Right: Maya artist, Mesoamerica. Mask. Wood, pigment. The Paul C. Johnson, Jr. Fund. 99.3.2. Native traditions changed to reflect the new European influences. This 19th-century Maya mask from Guatemala, for example, shows a Spanish conquistador.