Japanese Tiger and Dragon

Introduction

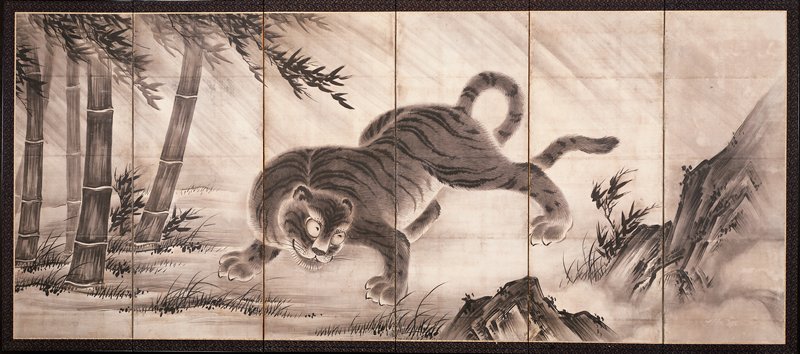

Imagine finding yourself between these two creatures, each painted on a wide folding screen standing five feet tall.

On your right, a dragon shoots into view from a swirling cloud. His motion whips the water below into wild waves. The dragon opens his mouth to roar, as tufts of hair and whiskers fly in all directions.

On your left, a tiger crouches low to the rocky ground. Steady and strong in the wind that bends the bamboo behind her, she silently eyes the dragon in the heavens. Not even her whiskers twitch.

Standing between these screens in a room might give you a sense of being in the middle of something big. For Japanese in the 16th century, they might have suggested the powers of the cosmos.

Doan (Yamada Yorikiyo), Japanese

Tiger and Dragon, ink on paper, around 1560

The Minneapolis Institute of Art

KEY IDEA ONE

The tiger and dragon are ancient symbols of yin and yang, forces that combine to make up the universe.

Ancient Chinese Taoist philosophy explains the world in terms of two forces yin (from the ancient Chinese word for shady) and yang (from the word for bright). Yang elements include light, fire, rain, and the heavens. Yin elements include darkness, water, wind, and the earth. Male traits are yang, and female traits are yin. Yang qualities are active, while yin qualities are passive. Everything in the universe results from the interaction of yin and yang.

The dragon and tiger have long been symbols of these two forces. The dragon, a mythical animal thought to reign over the heavens, stands for yang. The tiger, respected in ancient China as mightiest of the wild beasts, stands for yin. The screens illustrate why these two animals, both of them powerful and strong, are fitting symbols for yin and yang.

The tiger crouches low to the rocky ground, a sign that the yin earth is the tiger’s territory. Plants bend in the force of the wind, said to be created by the tiger’s mighty roar. But the tiger’s strength is a quiet power, held in her taut muscles. The dragon, on the other hand, is full of active energy. His head rises out of the yang heavens. His energy causes rain clouds to swirl and waves to form. But the tiger and dragon seem evenly matched. One will not dominate the other, just as the forces of yin and yang balance each other in the universe.

KEY IDEA TWO

Japanese ink painters in the 16th century borrowed ideas and art forms from China.

The ancient Taoist idea of yin and yang, and the symbolism of the tiger and dragon, came to Japan from China. The ideas had been absorbed into a form of Buddhism based on meditation, known as Chan in China and Zen in Japan. Zen appealed to the samurai warriors rising to power at the end of the 12th century. The simplicity and self-control of meditation was good training for the disciplined life of a warrior.

Warriors admired ink painting for similar reasons. It requires the simplest of materials, just ink, water, and paper. At the same time, it takes great control to use just one color black, thinned to grays with water to suggest a full range of tones, with just a few strokes. Once on the paper, a brushstroke cannot be changed.

Japanese painters of the 16th century modeled their style of ink painting on Chinese examples brought to Japan by Zen monks. They also adopted Chinese subjects. Many ink paintings feature Chinese landscapes, rather than Japanese scenes closer to home. The dragon and tiger theme pictured here was also borrowed from Chinese painting. No tigers lived in Japan, so the Chinese paintings were the Japanese artist’s main source of information about the animal.

Of course, art forms rarely transfer to another culture unchanged. Chinese ink paintings usually took the form of narrow hand scrolls or wall hangings. Japanese artists painted in those formats too, but they also often created similar scenes on much larger freestanding folding screens. The panels joined seamlessly at the folds to create a single, vast surface on which to paint. Such screens were well suited for the sparsely furnished rooms of typical Japanese buildings.

KEY IDEA THREE

This pair of screens might have decorated the public areas of a Zen monastery.

The goal of Zen is to come to a perfect understanding of the nature of the world. This understanding does not come from reading religious texts or saying prayers. Rather it comes from direct experience of the world, heightened by meditation and the guidance of a Zen master.

Strictly speaking, art has no place in Zen Buddhism. A serious Zen master would have considered painting and poetry a distraction from the important business of meditation. But in practice, Zen monasteries were important centers of art production in 16th century Japan.

This pair of screens might have decorated the public area of a Zen monastery. They were probably painted by Yamada Doan I, the first of three generations of painters with the same name. He was from a high-ranking warrior family and was lord of the Yamada castle. But he also became a Zen Buddhist monk, taking the name Doan when he entered the monastery. The skill and sure hand seen in these painted screens suggests that Doan was more of a professional painter than a serious monk. Nor did he abandon his warrior pasthe died in battle in 1571.

Related activities

What Would They Say?

Compose a conversation between the dragon and the tiger. What would they say to each other? How would their speaking style reflect their yin or yang nature? Consider vocabulary, tone of voice, volume, and other qualities. Compare your dialogue with someone else.

Shades of Gray

Examine the screens closely. Where is each image the darkest? Where is it lightest? Where does you see shades of gray? Gather a piece of white watercolor paper, some black ink or paint, a brush, a bowl of water, and a saucer for mixing. How many different shades of gray can you make? How would you make a patch of bright white?

Striped Like a Tiger

The painter of these screens most likely never saw a tiger firsthand. How similar is his picture of a tiger to a real tiger? Research the appearance and behavior of real tigers and list the similarities and differences you notice. Draw your own tiger based on what you learn from your research.