Animals in Art

Artists show their love of animals.

Idea One: The Elephant-Headed God

Indonesia, Eastern Java

Sailendra dynasty, Ganesha

volcanic stone (andesite)

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Purchase through Art Quest 2003 and

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

The Hindu god Ganesha has the body of a plump boy and the head of an elephant. A beloved and playful god, he is known as the lord of success and remover of obstacles. He is also associated with wisdom, knowledge, and prosperity.

There are many stories as to how Ganesha got his elephant head. In one popular version, Ganesha’s mother, Parvati, created him from clay to keep her company when her husband, Shiva, was away. The figure looked so real she decided to breathe life into it.

Parvati asked her son to guard her door. When Shiva returned he was surprised to find a young boy there, especially one who claimed to be Parvati’s son. After the boy denied him access, Shiva became angry, so angry that he cut off Ganesha’s head! When Parvati discovered what Shiva had done, she wept and begged him to find the head. Shiva looked hard, but couldn’t find it. He found an elephant that agreed to give him its head. He returned home and placed the elephant’s head on the boy’s body. Parvati breathed life into the boy again and he awoke.

Ganesha is seen as a guardian, and statues of him often decorate niches in Shiva temples. In this sculpture, a seated Ganesha eats sweetmeats from a bowl held in his lower left hand. His lower right hand grasps a broken tusk, while his other two hands hold a rosary topped with a pomegranate (a symbol of abundance) and an axe to ward off evil.

Cambodia

Bronze

Gift of Michele and David Dewey

Here is a family portrait. Shiva, the god of creation and destruction, sits with his arm around his wife, Parvati. Ganesha is seated near his mother’s foot. On the other side is Skanda, the god of war, who is Shiva’s eldest son.

c. 1000

buff sandstone

Minneapolis Institute of Art, The John R. Van Derlip Fund

Ganesha is often depicted in the seated lotus position. However, he is also frequently shown playfully dancing, mimicking his father, Shiva (Lord of the Dance).

12-13th century, bronze

Minneapolis Institute of Art

gift of Michelle and David Dewey

Shiva, Ganesha’s father, is depicted here in a dance pose.

Idea Two: Paintings of Pooches

Portrait of James Ward

1779, oil on canvas

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

They say a dog is a man’s best friend. Dogs also must be great pals with artists, because these furry, four-legged friends are often found in works of art. Sometimes the image of a dog is symbolic and meant to tell us something about its owner. For example, in many Renaissance and Baroque paintings, a dog is a symbol of fidelity. Other times a dog is seen as a treasured household member, who deserves a spot in the formal family portrait. And in some works of art a dog is not just part of the picture, but the main subject.

In this painting, a boy stands confidently with his arm around his dog. The pose, costume, and canine were all based on paintings by a prominent artist of the seventeenth century, Anthony van Dyck, who often included dogs in his portraits. He painted the dogs to match their high-society owners.

In addition to being the boy’s pet, this dog reveals some details about its owner. First, the artist cleverly discloses the identity of the boy by inscribing his name on the dog’s collar: J. Ward. Ten years old at the time of this portrait, James Ward loved animals throughout his life. He became one of the greatest animal painters of his generation and was commissioned by England’s Board of Agriculture to paint more than two hundred portraits of livestock on farms throughout the country.

Nicolas de Largilliere, Portrait of Catherine Coustard

c. 1699, oil on canvas

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The John R. Van Derlip Trust Fund

The placement of a dog in this portrait probably symbolized the virtuous nature of the woman.

1667, oil on panel Minneapolis Institute of Art

gift of Atherton and Winifred W. Bean

Dogs often made their way into family portraits. If you look closely at the painting you can see that a dog is nuzzling the hand of the woman.

James Ward (English, 1769–1859)

Crayon lithograph

Lee M. Friedman Fund

When Ward grew up he became a famous engraver and painter of animals, especially dogs and horses.

Idea Three: Let’s Monkey Around

1951, bronze

Minneapolis Institute of Art

gift of funds of the John Cowles Foundation

Estate of Pablo Picasso/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Late in his life, the artist Pablo Picasso became a father again, with the birth of his son, Claude, in 1947, and daughter, Paloma, in 1949. Picasso’s young children inspired new artistic ideas, and soon he was focusing on the subject of motherhood. In his art he explored the relationships between human mothers and children, and likewise animal mothers and their young.

What kind of animal adult and young are featured here? The long muzzle, close-set eyes, round belly, and straight tail gives us visual clues that this is a baboon. If you look a little closer you may be amazed at the objects Picasso used to form the figure. The head is made up of two toy cars that may have belonged to the artist’s young son. The body appears to be created from a large ceramic jug. And the tail could be a metal slat from a shutter or a car spring. Picasso added plaster and clay to form the furry neck and other details. After assembling all of the parts, he cast the sculpture in bronze.

Attached to the adult baboon’s chest is an abstract form of an infant baboon. Although there are not any recognizable features on the infant, its body position mimics the way a baby baboon clings to its mother. Female baboons tend to be the primary caregivers of their young and for the first month of the youngster’s life, mother and baby stick close together.

A closer look reveals the toy cars used to make the baboon’s head.

Idea Four: Heavenly Horses

Eastern Han dynasty

bronze with traces of polychrome

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton

Horses were highly prized in ancient China. The military and the elite wanted powerful horses for riding and pulling elaborate carriages. During the Han dynasty (206 BCE through 220 CE), a superior breed of horses was discovered in the Ferghana Basin in Central Asia (modern Afghanistan). The Chinese recognized their great value and decided to obtain these horses through military force and trade along the Silk Road.

These horses were stronger, faster, and larger than any horse in China and they quickly became symbols of power and prestige. Because of their endurance and speed they were labeled heavenly horses and were thought to have divine powers. Unusual red foam on their skin also earned them the nickname blood-sweating horses. (Actually a parasite-caused skin condition produced the foam when horses blood mixed with their sweat.)

This statue represents one of the heavenly horses from the Eastern Han dynasty. Its power is evident in its muscular form, arched neck and spirited expression. Statues such as this one were placed in the tombs of aristocrats, along with replicas of dogs, pigs, chickens, dancers, and musicians to provide for the dead in the afterlife.

Originally, this bronze horse was painted. Today, the bronze has corroded to beautiful green and blue tones. Black, red, and white pigments are still visible around the eyes, mouth, and mane.

Funerary Model of a Pig Sty

earthenware

Minneapolis Institute of Art

gift of Alan and Dena Naylor in memory of Thomas E. Leary

Horses weren’t the only animals to decorate tombs. This model houses a clay boar, sow, and suckling piglets.

earthenware with traces of pigment

Minneapolis Institute of Art

gift of Ruth and Bruce Dayton

Not all horse figures were made of bronze; this heavenly horse was made of clay. How does the shape and stance of this horse compare to Celestial Horse?

Idea Five: The Thrill of the Hunt

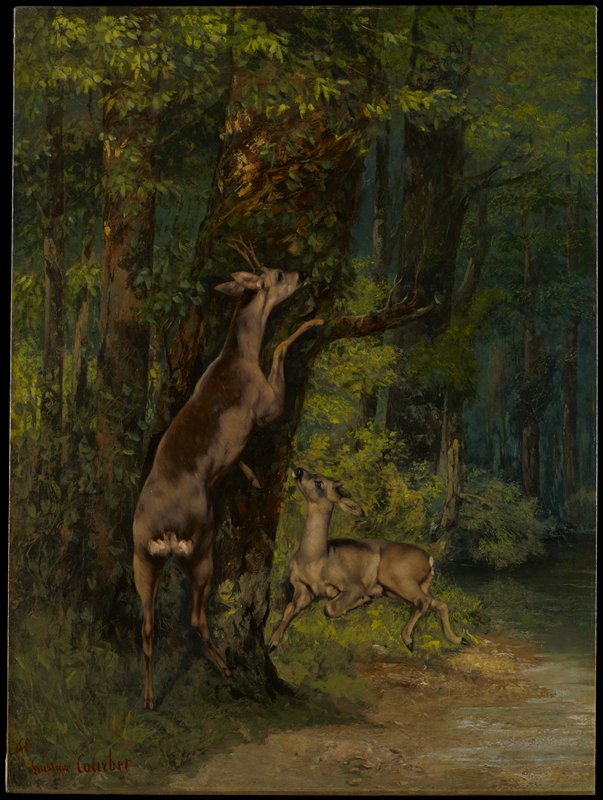

1868, oil on canvas

Minneapolis Institute of Art

gift of James J. Hill

People have enjoyed hunting for centuries. For some people, hunting is a matter of survival. But for the elite, it is more a stylish pastime than a necessity. Recreational hunters love the thrill of the chase and the satisfaction of a successful adventure. Because of the sport’s popularity, pictures of hunting escapades have been fashionable throughout time.

The artist Gustave Courbet was an avid hunter. His passion for the sport, along with the demand for hunting images, inspired him to paint numerous outdoor scenes. In fact, he painted more than thirty hunt pictures from 1850 through 1873. Some were paintings of hunting parties in action out in the field. Others were more peaceful scenes depicting animals at rest in their natural surroundings. Regardless of the scene, Courbet always tried to paint the animals in a sympathetic way.

Here we find two deer in a lush, wooded environment. Both are helping themselves to a tasty snack of tree leaves. The antlers on the deer in the foreground tell us that it is a stag (male). The deer in the background is probably a doe (female) because its antlers are very short. Courbet captured both deer in a moment the stag is up on his hind legs as he reaches for leaves and the doe’s curved legs show that she is resting on the grass. If Courbet painted this pair out in the woods, he would have had to make quick observations to catch their movements. Deer are rather skittish animals and wouldn’t have been the best models to work with. Therefore it is believed that for some of his scenes, Courbet borrowed deer from a Parisian butcher.

1855, oil on canvas

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the William Hood Dunwoody Fund

Courbet loved nature, and painted both animal scenes and landscapes.

c. 1650, wool, silk; tapestry weave

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

stoneware with painted decoration on white slip under a clear glaze

Minneapolis Institute of Art

gift of Eskenazi Ltd., London, in honor of Ruth and Bruce Dayton

Deer have been the subject of art for various reasons. According to the Taoist philosophy, a deer is an auspicious symbol.

Related Activities

Pet Portraits

Do you have a pet or a favorite animal in nature? Spend a little time observing the animal. What features do you see? What kind of personality does it have? Does it have distinctive abilities? Create a portrait of the animal emphasizing what makes it so special.

Piece It Together

Picasso made _Baboon and Young_ from a variety of everyday objects. Look around your house. What could you use to form a giraffe’s neck? An elephant’s trunk? A lion’s mane? Make a sculpture of an animal with found objects.

More Animals in Art at Mia

Check out many more Mia artworks from around the world that feature animals, using the search feature on the museum’s website. Or, if possible, make a trip to the Minneapolis Institute of Art to see hundreds of animal art objects in the galleries. You could even count how many you see!

Watch and Learn

Check out the different animal cams from the Smithsonian National Zoological Park. You can watch live video of elephants, lions, pandas, and more of your favorite animals! Keep a journal of your observations, what the animals are doing, how they interact with one another, and what they like to eat. For more information, see the Smithsonian’s animal fact sheets.

Stories of Ganesha

There are hundreds of stories about the loveable Hindu god, Ganesha. Read stories in the children’s collection, _The Broken Tusk: Stories of the Hindu God Ganesha_, by Uma Krishnaswami (North Haven, CT: Linnet Books, 1996). Choose a character from one of these tales and make an outline of the character’s actions, motives, emotions, traits, and feelings.