Building a Museum

The dreams of Twin Cities art lovers of a century ago continue to take shape.

Idea One: A Temple of Art

Massive marble columns. Gleaming blocks of stone. Walls the length of a city block. A sense of the city’s pride bursts from this postcard of the Minneapolis Institute of Art from about 1915.

Just a few decades earlier, Minneapolis had been barely more than a large town. Thanks to the success of its flour mills and the railroads, it exploded in size. It grew from 47,000 people in 1880 to 129,000 people in 1885. But with the city’s commercial success, people wondered how to avoid the gross materialism that could come with such a boom.

Art was the answer, some said. Industry without art is brutality, proclaimed a Tribune newspaper editorial in 1882. In 1883, fourteen men and eleven women formed the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, devoted to building an art culture in Minneapolis. They dreamed of a temple for art and music with galleries, an art school, and an orchestra hall.

At first the Society rented rooms in the public library downtown. They had a single room for exhibitions and owned six works of art. By 1911 the Society’s members had raised enough money to build their own building though not the whole project pictured on this postcard. Only the center section of this view was ever built.

The drawing on this postcard from about 1915 shows the original plan for the Minneapolis Institute of Art as it would have looked from the corner of Stevens Avenue and 24th Street.

The Society of Fine Arts got its start in rented rooms in the public library building in downtown Minneapolis.

Clinton Morrison promised to give his family’s homestead on Third Avenue and 24th Street to the Society of Fine Arts if they could raise \$500,000 for a new building.

The Society began construction on the new building in 1913.

Idea Two: A Grand Vision

The original plan for the Minneapolis Institute of Art was ambitious. It was designed by the most famous architectural firm of the day, McKim, Mead and White. The museum was to extend the full length of the block on 24th Street. Wings along Third Avenue and Stevens Avenue would house an orchestra hall and an architectural hall. The classical style recalled grand European buildings, from the monuments of ancient Rome to the palaces of French kings.

The “Institute” was designed to be built in sections, as money was raised. The full project would have cost two million dollars at the time. The Society had raised \$520,180 by 1911. With that money they built the central part of the art museum, about one-seventh of the whole design. They planned to add the wings for music and architecture later.

Since it opened in 1915, the museum has expanded four times, in 1926, 1974, 1998, and 2006. With the 2006 addition, it finally fills the entire block along 24th Street and extends down Stevens Avenue. It spans an area equal to seven and a half football fields. A visitor will walk almost a mile to see all the galleries.

The 2006 expansion adds another wing to the museum. It includes over thirty new galleries, two art study rooms, a library, and a large space for parties.

This model shows the original plan for the museum complex. It was designed to be built in sections. Only one-seventh of this plan was ever built.

This view of Mia from 24th Street shows three different eras of construction the classical 1915 building on the left, the clean modern lines of the 1974 addition in the middle, and the warm echoes of both in the 2006 addition on the right.

Some things never change the building’s first elevator, installed in 1930, still carries visitors from floor to floor in the original part of the museum.

Idea Three: Galleries Full of Gifts

Construction of the new museum began in 1913. But a very important part of the project was still missing: world-class art to display in the galleries. The Society of Fine Arts had hoped to attract the city’s largest private art collection, owned by the lumberman T. B. Walker. But Mr. Walker wanted a museum closer to downtown and eventually opened his own museum, today’s Walker Art Center.

The first director of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Joseph Breck, had only a few thousand dollars to spend on art in 1913. That was a slim budget even in those days. Then in February of 1914, everyone got a big surprise. The Society’s president, mill owner William Hood Dunwoody, suddenly died. Without telling anyone of his plans, he had left the Society a fund of one million dollars for the purchase of art. Gifts of money and artwork from others quickly followed.

Today the museum has nearly 100,000 works of art in its collection. About 5 percent of the art is on view in the galleries at any given time. The rest is kept in storerooms where temperature and humidity are carefully controlled. (Much of that art can be damaged by light and cannot be displayed for long periods.) Now, the 2006 expansion has added 40 percent more gallery space to the museum. Hundreds of treasures have come out of storage and the museum has room to add art to its collection for years to come.

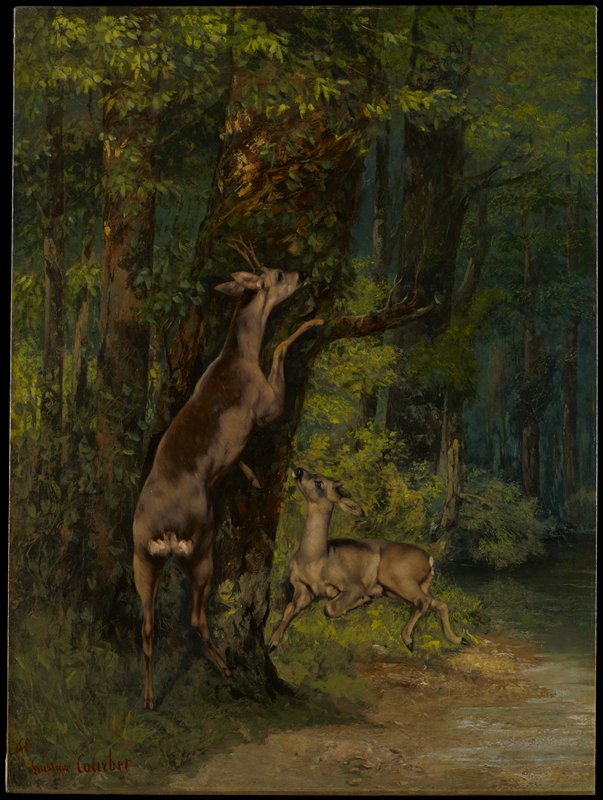

Gustave Courbet’s Deer in the Forest was one of the first paintings in the MIA’s collection. It was a gift of the St. Paul railroad tycoon James J. Hill in 1914.

Mia gained a world-class print collection overnight in 1916 when the newspaper publisher Herschel V. Jones bought the collection of another art collector for the museum. The collection included this 1630 self-portrait by Rembrandt.

The museum continues to buy art with interest earned from William Hood Dunwoody’s 1914 gift of one million dollars. The fund helped buy this Indonesian sculpture of the Hindu god Ganesha in 2003.

Collectors Bruce and Ruth Dayton have a wide variety of art interests. In the 1990s they worked with a museum curator to build an important collection of Chinese furniture including two authentic Chinese rooms in which to display it.

Idea Four: Behind the Scenes

As the museum has grown, so has the number of people needed to keep it running. In 1923, twenty-seven people worked at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Even so, the new director, Russell Plimpton, sometimes found himself washing dishes at receptions. In 2018, the museum has 268 employees and 396 volunteers. Here are some of the jobs in the museum today:

Curators take care of the museum’s works of art. They shop for new art and build relationships with collectors who may want to give their art to a museum someday. Curators decide what art to hang on the walls and how to arrange it and also write labels to help visitors understand what they see.

Registrars keep track of each work of art, including information about how it came to the museum and its location.

The art crew moves art around the museum, builds display cases, and paints gallery walls.

Security guards patrol the galleries, helping visitors and making sure the art is safe.

Advancement officers raise money for museum projects from companies and individuals looking for ways to contribute to society.

Marketers and public relations staff spread the word about museum activities through advertising and news stories.

Educators engage visitors of all ages in a wide range of experiences, prepare information about the collection, and train volunteers to lead tours of the museum.

Volunteer docents and guides lead visitors on tours of the museum. (The word docent comes from the Latin word for teach.) Many of them give more than 50 tours a year each.

Members of the art crew use ropes and a lift to hang very large paintings on the wall.

Security guards patrol the galleries. Guards walk three to five miles a day.

The art crew carefully moves a 1936 automobile to its place in the new Modernist Design galleries.

A curator consults with a workman re-creating a room from 18th-century Paris.

Idea Five: A Museum for the People

The opening of the museum in on January 7, 1915, was a triumph for the members of the Society of Fine Arts. Three thousand people came to the opening night party. The newspaper the next day described it as one of the most brilliant social events of the winter.

But the opening of the museum was not just an event for socialites. Over 12,000 people visited the new museum on its first day. That was the most people ever to visit an American museum outside New York City in a single day. And as the newspaper noted, comparatively few automobiles were drawn up before the MIA, most visitors being of the unpretentious sort who walk or ride streetcars. Over 80,000 visitors had passed through the museum by the end of the month.

The Minneapolis Institute of Art continues its mission of serving the people of Minnesota. Around 500,000 people visit every year. There is no charge to get in; this is one of the few free museums in the country. And these days, the Internet allows millions more people around the world to enjoy the collection of art that was just a dream a century ago.

More than 60,000 students visit the museum on school field trips each year.

A school group visits the museum in 1915.

A school group visits the museum in 2005.

Related Activities

A City Grows

Get a sense of the rapid changes in early Minneapolis by viewing old photographs of the city taken between 1870 and 1890, from the collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. What looks different from today? What looks familiar?

Postcard from Minneapolis

The first image in this feature comes from a postcard sent by someone in Minneapolis around 1915. Imagine you had visited the museum on its opening day. What might you have written on the postcard?

Combining Scenes

To produce his final paintings, Albert Bierstadt combined elements from several different pictures. Take photographs or make sketches of various scenes in your community. Then combine elements from different scenes a building from one, a tree from another to create a collage or a painting.

View FSA Photographs

View thousands of Farm Security Administration photographs taken by Walker Evans and many other photographers during the Great Depression on the Library of Congress website .