From Farm to Table

Go on a delicious adventure to learn about food-related artworks from around the world.

Idea One: Fresh from the Fields

Look closely at this painting. What seems to be going on?

This scene of rice threshing, hulling, and winnowing is from a set of sixteen painted screens showing the activities of rice farming. The screens formed the walls of the emperor’s reception room at Saga Castle in Kyoto. Why did the emperor of Japan want to be surrounded by paintings of humble farmers cultivating rice?

Rice represented the emperor’s connection to heaven and his right to rule. According to the Japanese creation story, the first emperor, Jimmu, brought rice seeds with him from heaven. When he planted the seeds, Japan was transformed from a wilderness into a land of abundance. Although rice actually came to Japan by way of China, around 350 BCE, the story of Jimmu linked rice crops and harvests with Japan’s emperors. (Even today the emperor tends a small rice paddy on the palace grounds.) These paintings would have reminded the emperor’s guests of his divine authority.

Rice was very important in Japanese life. During the Edo period (1615–1868), wealthy and powerful people kept impressive stores of rice, and landlords measured their worth by how much rice their peasants produced. Samurai received their stipends in rice, and peasants paid their taxes in rice. Even though they grew this valuable crop, peasants rarely ate rice. Instead, they generally had millet or sweet potatoes, saving rice for special occasions or ceremonies.

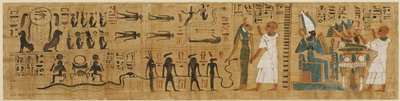

In ancient Kemet (Egypt), influential people like rulers and priests were buried with papyruses that helped ensure their safe passage to the afterlife. This funeral papyrus features the dead person offering foods including onions and grapes to the god Osiris, who watches over the entrance to the afterlife. What other foods do you recognize?

The French Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro often depicted people working harmoniously with nature to preserve the beauty and simplicity of country living. The peasants in this scene are harvesting a field of beets.

Daikoku is the god of agriculture and bountiful harvest in Buddhist-inspired Japanese folklore. He is often shown standing on rice bales (representing good harvests) and holding a magical mallet that can bring prosperity.

Idea Two: The Kitchen as Laboratory

What words describe this kitchen? What familiar items do you see? In what ways is this kitchen similar to or different from your own?

Before the 1920s, people in Germany used kitchens for many different activities: cooking, playing, eating, bathing, and even sleeping! Kitchens were not very clean or well laid out. In the 1920s, the Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky designed a kitchen for the very small apartments of Frankfurt’s low-income housing projects. Lihotzky’s “Frankfurt kitchen” is tiny by modern standards, but its compact layout encouraged efficiency and good hygiene. Using time-motion studies, Lihotzky planned the space so that people would take fewer steps while preparing food. Fewer steps meant time saved—and spills avoided.

Lihotzky made the most of the small space by including built-ins like a countertop trash bin for easy cleanup and an ironing board that folds up into the wall. She modeled her kitchen after a laboratory, promoting cooking as a precise science. The room even looks a little like a laboratory, with industrial cupboards, a stool, glass doors, and an adjustable track light on the ceiling. This kitchen was easy to keep clean. Lihotzky did away with nooks and crannies where crumbs and pests could hide. Even the color of the cabinets was chosen with a purpose. Researchers at the time had reported that flies would not land on blue surfaces!

Take another look at the kitchen. Do you notice anything missing? When the Frankfurt kitchen was designed, few homes had refrigerators. People bought fresh food from markets every day.

The joy of cooking! This lively drawing shows an outdoor cooking scene in Persia (modern-day Iran). Created during a time of relative peace and prosperity, illustrations like this celebrate the joys of life, luxury, and high culture.

In this image by the famous print artist Kitagawa Utamaro, Japanese women are cooking a meal together in a crowded kitchen. What activities can you identify?

An early form of refrigerator, this Chinese ice chest was designed to keep food and drinks cool. In summertime, it could even cool a room!

Idea Three: Dinner is served …

Imagine eating a meal with utensils like these! Would you want to eat with this fork?

Today, forks and knives are common at many tables, but this was not always the case. In the Middle Ages, most Europeans—even kings and queens—ate with their hands. People used knives to cut their portion from a serving tray. Forks were not introduced to Italy until the 11th century, when a visiting Byzantine princess brought her knife and fork along. Upon seeing her use the fork, her royal hosts were quite shocked! However, the Italian nobility did, eventually, take up the fork.

Until the 17th century, people generally brought their own cutlery to a meal. This rare set once belonged to someone important and was likely saved for special occasions. Fellow banquet guests would have admired its beautiful coral decoration and lavish inlay, evidence of the owner’s high rank and good taste. The coral also suggests a concern for safety, since coral was believed to be an antidote to poison. A high-ranking person might well have had cause to worry!

This Ethiopian agelgil is used like a lunch basket to carry a type of flatbread called injera

Among Native Americans of the Plains and Great Lakes/Woodland regions, wooden bowls like this one were widely used for everyday purposes. The carved head may represent Eyah, the spirit of eating heartily.

A wedding feast! The table here is set up to celebrate a wedding with a nine-course meal that includes cakes, melons, and dumplings.

Idea Four: A Feast to Celebrate!

In this two-story house, people are shown feasting with their ancestors. How do you honor your ancestors?

Two thousand years ago, the people of Nayarit, in what is now western Mexico, believed the dead lived just below ground, separated only by a thin barrier from the world of the living. Sculptures depicting familiar activities were buried with deceased family members, to keep them company in the afterlife. This two-story ceramic house is such a tomb sculpture. A family on the upper level (the world of the living) is enjoying a feast with their ancestors, who occupy the lower level (the realm of the dead). Some in the upstairs group are gathered around a plate of food—likely corn or tamales—while others relax outside. The figures below echo those above, with similar postures and their own bowl of food.

Feasts were a central part of life in ancient Mesoamerica. People held feasts to celebrate major life events, to forge political and economic bonds, and to honor the dead. The various feasts corresponded to the seasons and often featured foods such as corn and tamales. At all levels of society, ritual feasts were occasions for honoring people and displaying status. Rulers reinforced their power by throwing huge feasts for their subjects. And feasting maintained and strengthened family ties among the living and the dead.

In this painting, John Singer Sargent captured an intimate birthday celebration with his own close friends. How do you celebrate your birthday?

Weddings are great occasions for feasting. This tapestry, woven of wool and silk and silver yarns, pictures a 16th-century wedding banquet out in the country.

Idea Five: Sweets and Treats/Sugar and Spice

What words describe this utensil?

This ornate object is a sugar hammer, used for chipping pieces off a cone-shaped sugar loaf. Rock-hard sugar loaves are popular in Morocco, where tea enthusiasts accept no substitute for sweetening their mint tea. To break off pieces of sugar, you simply aim the blade at the loaf and take a whack! Though sugar hammers have gone out of fashion in America and Europe, they remain a useful, elegant utensil in Moroccan tea culture.

Now almost unique to Morocco, sugar loaves were once the only way sugar was sold. Granulated or cubed sugar is a fairly recent convenience. Sugar comes from the sweet sap of sugarcane, a thick, stalky grass. To make the loaves, harvested stalks are crushed to release their sap. The sap is boiled and then poured into cone-shaped clay or iron molds and left to dry for a few days. A small hole at the tip of the mold allows liquid (molasses) and any impurities to drain out as the sugar inside crystallizes into a solid cone.

This sugar hammer combines design with function. Moroccan metalwork tends to be highly decorative. It often features repeating geometric patterns, as seen on the gently curved blade of this hammer, which is also embellished with studs. The handle has a convenient loop at the end for storage. This practical tool is a beautiful accessory for a spot of tea.

The Maya regularly enjoyed a chocolate drink made of ground cacao beans, water, cornmeal, chilies, and honey. They poured the mixture back and forth, until it got frothy, and then drank it out of a vessel like this one.

Spanish colonists in the New World modified the chocolate drink of the Maya to suit European tastes. By the 17th century, chocolate was a popular drink in Europe, along with coffee and tea.

Salt is important in cuisines throughout the world, for preserving food and adding flavor. In Europe and America, before salt shakers became popular, salt was placed on the table in saltcellars, from which people could take a pinch.

Related Activities

Kitchen Remodel

Design the ideal kitchen for your family or friends. As you draft your plans, consider the activities that will go on, storage and other needs, and safety. For extra fun, design a new kitchen gadget or utensil.

How Does Your Garden Grow?

Work as a class to design and plant a class garden. Research and think about the space requirements, the kinds of plants you can grow, and how much money you would need. Check out the [ let’s move.org archives](https://letsmove.obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/school-garden-checklist) for more ideas and tips.

The Art of Food

Play with your food! In Japan, many schoolchildren enjoy boxed lunches called bento. Bento are both imaginative works of art and healthy meals! Use your imagination to sculpt, draw, or otherwise create a work of art from nutritious foods. What kinds of foods will you use for your appetizing art? Check out [these bento boxes and characters](http://www.annathered.com/gallery/bento/)!

Food Traditions

Interview some adults about food traditions they remember from the years when they were growing up. What kinds of foods did they eat? Where did their food come from? Think about how their experiences are similar to or different from your own. Why do you suppose some things changed while others have stayed the same?

World Hunger and You

Many people around the world and in your own community do not have enough nourishing food to eat. Innovative designers can play a big role in helping solve this problem. Check out the [“Solutions” page](http://www.designother90.org/solutions/?exhibition=12) at the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum at the Smithsonian Institution: Cooper Hewitt. How have designers addressed food and hunger problems around the world? Use your imagination to design your own solutions. What actions can you and your classmates take to help in your community?

What’s for Lunch?

Check out the book What’s for Lunch, by Andrea Curtis. Then take a peek at the discussion questions and activities in the teacher resource at the What’s for Lunch blog: [unpackingschoollunch](https://unpackingschoollunch.wordpress.com/tag/school-lunch/). What important role does food—and school lunch—play in the daily lives of people around the world?