Identity and Prestige in Mayan Textiles

Discover how the designs of Mayan textiles from Mexico and Guatemala communicate identity and status.

Idea One: Honor through Dress

Maya

Whistle, 7–10th century

Ceramic, pigment

Minneapolis Institute of Art

The John R. Van Derlip Fund

The ancient Maya are well known for their highly developed written language, art, architecture, and mathematical and astronomical systems. Today, Mayan people live in Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, and El Salvador.

This ceramic figure is a hand-sized whistle that was buried with an important person on the small island of Jaina (hi-nah), the site of the largest known Mayan necropolis, or cemetery. The figure’s prestige dress indicates burial with an important person. The short layered skirt, decorated in blue stripes, has a long panel that falls to the feet. Neatly combed hair, feathered headdress, and earrings are all signs of an elaborate ceremony.

Characteristic physical alterations enhance the figure’s appearance. Mayan boys of this time period endured physical manipulation of their facial features to obtain the arched nose and flattened brow seen in this figure, desired features for Mayan men. Babies’ heads were bound and shaped to grow upward and tall, not round, to align the forehead with the tip of the nose.

What words would you use to describe this masculine figure’s facial expression? His face, arms, and legs are painted red, in imitation of the prestige practice of painting the deceased with iron oxides. His feet are firmly planted and his arms crossed over his chest, showing strength and pride, perhaps to communicate that he was honored for a significant accomplishment.

c. 1960, wool, silk, cotton, embroidery

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

This jacket would have been worn during ceremonies, perhaps with special permission from the village priest. The fancy eye-catching embroidery would remind everyone of the wearer’s prestige. Guatemala, El Quiché (el keesh-ay), Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (chee-chee-cas-te-non-go).

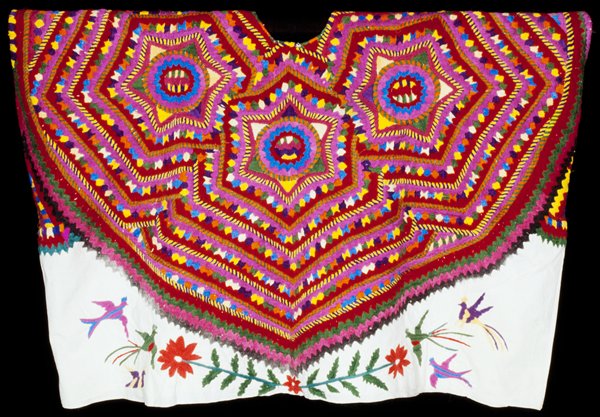

Mexican, 20th century, Wedding Huipil, cotton, feathers,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons

The addition of feathers to this huipil (we-peel) (woman’s blouse) indicates it is not for everyday use, but for a wedding. This huipil is unusual in that the weaver is known and identified.

Idea Two: Village Identity

Tzute, (tsoo-tay) 20th century

Cotton; supplementary weft patterning

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

Each Maya village highlighted in this feature has a unique approach to weaving or embroidery. Villagers identify the origin of these textiles through their distinctive designs and colors.

The designs on many huipiles (we-peel-ays)—loose blouses worn by Mayan women—and other woven or embroidered Mayan textiles are symmetrical, or balanced, especially from side to side. By contrast, the weavings of the highland village of Santa Apolonia are recognizable by their asymmetry. The arrangement of shapes and colors in the Santa Apolonia designs appear more random.

The design on this tzute, a head covering or all-purpose carrying cloth, is asymmetrical whether viewed from side to side, or top to bottom. Notice the three bands of designs at the top of the wrap. Then see how a single band at the bottom repeats the shapes used in the first and third rows on the top. Between is an expanse of white space. By folding the tzute, the wearer could alter the garment’s appearance. The woven shapes are distinctive and unusual. How would you describe these shapes?

San Mateo Ixtatán, Huipil,

20th century, cotton, embroidery,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard and Roberta Simmons

This huipil is from San Mateo Ixtatán, near the Mexican border, far away from other Guatemalan centers of textile production. The style of dense embroidery resembles that of Chiapas, Mexico.

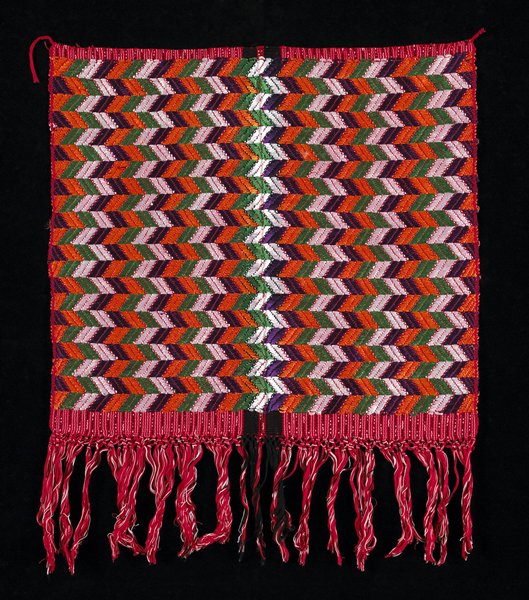

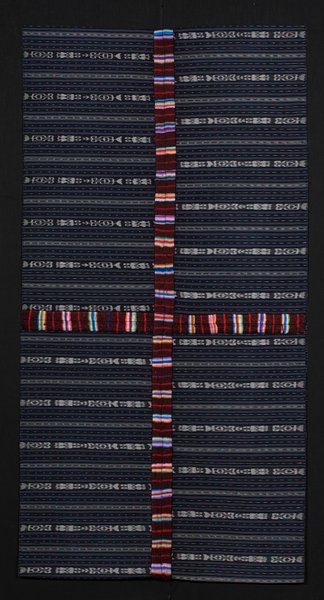

Almolonga, Man’s Ceremonial Tzute,

20th century, cotton, rayon:

jaspé (hahs-pay) ikat (ee-cot), and supplementary weft patterning,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

The textiles of the Guatemalan village of Almolonga (al-moe-loan-gah), located nine miles from the state capital of Quezaltenango (ket-zahl-te-non-go), are recognizable by their parallelogram or zigzag patterning and alternation of colors, designs that date back to the first half of 20th century. In this man’s ceremonial tzute, or head covering, the repetition of orange, green, white, and purple parallelograms makes an eye-dazzling display that creates an optical illusion.

Woman’s Cofradia Huipil, c. 1910–20, cotton, silk;

supplementary weft patterning,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

A unique practice in the village of Nahuala (nah-wall-ah) intentionally allows the dye from silk threads bleed onto the white base fabric. In this cofradia huipil (co-fra-dee-a we-peel), the red from the expensive silk thread has bled onto the white fabric. By allowing the thread to bleed, the wearer is showing that she has an expensive item, woven with silk thread.

Idea Three: Shapes and Patterns

Huipil, 20th century

Cotton; supplementary weft patterning

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

Look at the shapes and patterns on your clothing. What do you like about them? Why do you think a clothing designer might have chosen these particular designs?

Look carefully at the geometric patterning on the lower portion of this huipil. Notice the alternating patterns and combinations of green, lavender, black, light blue, blue, green, turquoise, purple, red, magenta, yellow-green, and white. The shapes include triangles, interlocking vertical zigzags, diamonds, and parallelograms. The wearer of this huipil would have earned admiration and attention as she walked through her village.

Woven and embroidered Mayan textiles are full of shapes and patterns. Typically, geometric shapes indicate an older design, and more naturalistic shapes indicate a newer one. Many newer textiles, however, use geometric designs as a reference to the traditions and history of Mayan art.

The village of San Antonio Aguas Calientes (which means “hot waters”) is near a volcano. The women there are among the most prolific back-strap weavers in Guatemala, producing textiles for local, regional, and even international markets. This huipil is an example of marcador (mar-kah-door) double-faced (or reversible) weaving, a technique that originated in the 1930s. The artists used European sources as a basis for the designs of flowers, fruit, birds, and leaves on the shoulders. Because of their complex and difficult-to-make designs, the marcador huipiles from San Antonio Aguas Calientes are expensive. People there and in other villages consider these high-status symbols. The blue velvet edges on the neck and armholes may indicate that this huipil was sold and worn in a different village.

This huipil is made in the older style of complex geometric motifs in the village of San Antonio Aguas Calientes. It features zigzags, triangles, diamonds, trapezoids, parallelograms, and dots, separated by bands of plain weave for contrast.

This densely woven and dazzling tzute has many examples of shapes. In addition to birds, donkeys, and people, there are complex layers of triangles, radiating diamonds, and parallelogram.

Idea Four: Designs as Symbols

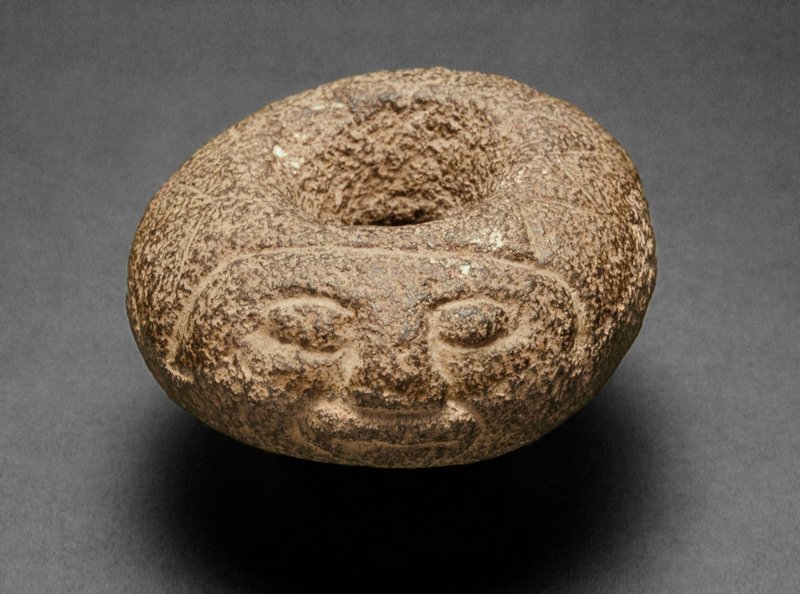

Ceremonial Spindle Whorl, 10th–15th century

Stone

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Mrs. Stanley Hawks

The clothes you’re wearing might bear a design, like an animal print, flowers, or soccer balls. Are the designs symbolic of something else? What do they say about you?

As in many cultures, the sun was and is a powerful symbol of energy and creation for the people of Guatemala and Mexico. This ceremonial stone spindle whorl features sunrays above a beaming sun face. A spindle whorl is set atop a wooden stick to form a tool; it is used to spin natural fibers into thread for weaving and other textile production. The spinner, most likely a woman, set the spindle in motion by spinning the stick between her hands, or in a ceramic bowl made for the purpose. The whorl provides the weight necessary for the fibers to spin around each other and lock together, resulting in thread. This particular spindle whorl, however, seems to be too heavy for that task; instead, it may have been used in ceremonies, or perhaps buried with a weaver or person of high rank.

The act of spinning can refer to the Mayan goddess Ixchel (ee-shell), who is considered the goddess of weaving and associated with the beginning of the world. So not only is a spindle whorl a tool, it is also a symbol for the creation of the world, birth, and weaving. It might have served as a reminder that the sun, spinning, and weaving all produce something, and are all connected.

Man’s Bag, 20th century, cotton, acrylic,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

This bright bag features popular representations of birds and horses, along with a repeating stripe design.

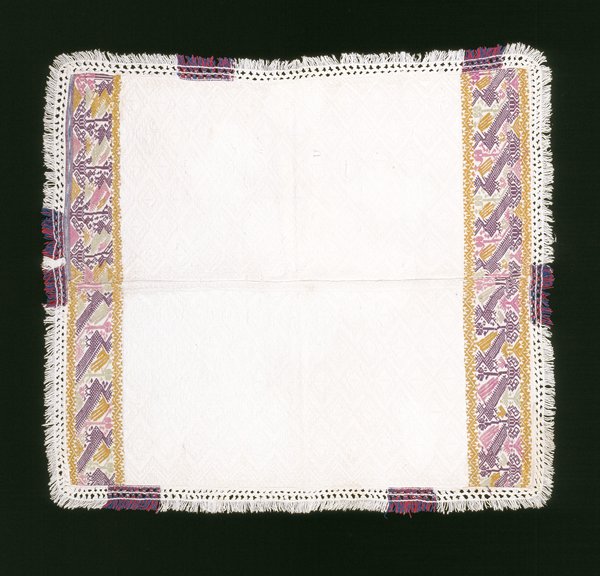

Cofradia Tzute, 1955–60, cotton;

supplementary weft patterning,

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Richard Simmons

The gold and purple brocaded birds and trees are commonly found in weavings from Quetzaltenango. This tzute would have been used in special saint’s day celebrations.

Santo Tomas Chichicastenango,

Man’s Ceremonial Pants, c. 1960, wool, silk, cotton, embroidery,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

These pants were once worn with a ceremonial jacket and would have made a powerful statement about the wearer’s importance. The intricate circular design evokes the sun and is surrounded by a profusion of plants.

Idea Five: Wearing a Work of Art

Man’s Hat, c. 1990

Palm fibers, satin, acrylic

Minneapolis Institute of Art

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

The ancient art of textile weaving is thought to originate in the even more ancient art of basket-making. Both employ the primary technique of a base fiber (the warp) intertwined with a working fiber (the weft). Hats such as this one from Chiapas are woven using the same concept as basket-weaving.

Weaving is a time-consuming art, and this hat would have taken many days to make. First, the artist gathered the palm fibers and prepared them for weaving. While weaving, he would have shaped the fibers into the form of a human head. The huipiles and other clothing in this feature would have taken six to eight weeks to make, woven on a portable back-strap loom.

Think about your favorite outfit. Where did it come from? How do you think it was made? How long do you think it took to make? How do you feel when you wear it? Do you think it is a work of art?

This jaunty hat, with its shiny ribbons, would bounce as the wearer walked, calling attention to the rest of his outfit. Its main purpose was to guard from the sun’s rays, but the artist has added a colorful pompom and streaming ribbons for a festive touch. Wearing this hat, the owner probably felt proud and confident.

Woman’s Everyday Huipil, c. 1965, cotton, silk,

synthetic; supplementary weft patterning, embroidery, appliqué,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

Many huipiles show the rays of the sun around the collar. When worn, the woman’s head is surrounded by sunrays, putting her at the center of her universe.

This woven skirt goes with the huipil in the image above. The complicated weaving technique of jaspé (or ikat) requires great skill to determine the design’s placement in the finished fabric. The yarn is first tied, then dyed and woven.

Santo Tomás Chichicastenango, Sash,

c. 1965, silk, cotton; embroidery,

Minneapolis Institute of Art,

Gift of Richard L. Simmons in memory of Roberta Grodberg Simmons

This sash completes the outfit in these related images. The bright orange, pink, and blue triangles on one side contrast with the black and beige stripes of the other. The many tassels on the ends would bob and sway as the wearer moved.

Related Activities

Who are the Maya?

The ancient Maya are well known for their highly developed ancient written language, art, architecture, and mathematical and astronomical systems. Research the ancient and contemporary Maya. Where do the Maya live today? As part of your research, visit Maya Adventure here, a Web site developed by the Science Museum of Minnesota, which includes a section on the textile arts of the Chiapas Maya

Check out these books

Abuela’s Weave, by Omar S. Castaneda; Angela Weaves a Dream, by Michéle Solá; Mayan Weaving: A Living Tradition by Ann Stalcup; You Can Weave!: Projects for Young Weavers, Kathleen Monaghan and Hermon Joyner.

Shapes on the Move

Click here to visit Artist’s Toolkit to learn more about shape, balance, movement, and rhythm. Draw three shapes that you find particularly interesting in the works of Mayan art in this set. Then draw a pattern made up of your favorite Mayan shapes. Is your pattern balanced? How will you create a sense of movement in your pattern?

Every Garment Tells a Story

Huipiles (we-peel-ays) and other Mayan textiles go through various stages of use. Initially they are worn as a garment. Then they are passed on to younger family members. As they wear out, they are cut into smaller pieces, and eventually used as diapers! Write a history, real or imagined, of one of your garments.

Textiles Around the World

Go to ArtsConnectEd to view an Art Collector’s set of Mayan textiles in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Click here. How do these textiles relate to the objects and textiles highlighted in this feature? Then, use the art-finder tool in ArtsConnectEd to search for textiles from other parts of the world. Using the Art Collector tool, create a collection of your top 10 textiles from around the world.

What Do your Clothes Say About You?

Imagine you are getting ready to pose for a photo that many people will see. What are you going to choose to wear? Why? What does your choice of clothing communicate about your identity? How does what you choose to wear affect how you feel?”