Insects in Art

Even the smallest creatures can inspire artists.

Idea One: A symbol of rebirth

Scarab, 1504-1450 B.C.,

green-glazed steatite

Note: The number painted on the scarab’s back is the museum’s inventory number.

Scarab beetles, also called dung beetles, roll balls of animal dung across the ground and then bury them in underground nests. Thousands of years ago, the ancient Egyptians noticed this habit and associated it with the way the sun moves across the sky each day. The scarab became for them a sacred symbol of the morning sun. Khepri, the god of the rising sun, was pictured with a scarab-shaped head.

Female scarab beetles lay their eggs inside the dung balls. The larvae that hatch from the eggs feed under ground and later emerge from the earth as adults. Unaware of this hidden stage of the beetle’s life, the Egyptians believed scarabs were born magically from the earth; so scarabs came to stand for rebirth and renewal.

As symbols of rebirth, stone scarabs were often placed in Egyptian tombs. Scarab amulets, or charms, might be sewn onto the wrappings of the dead, particularly over the heart. Inscribed on the heart scarab’s underside were writings from the Book of the Dead, a plea that the heart not betray it’s owner when he or she sought entry to the afterlife.

Living Egyptians wore small stone scarabs as good luck charms. These could simply be strung on a cord and worn around the neck, but jewelry featuring scarabs also included more elaborate necklaces, bracelets, and rings. Often an important name, message, prayer, motto, or design was inscribed on the scarab’s underside.

This scarab was used as a seal to make imprints on documents or other objects. The oval on each side, called a cartouche, contains the name of a king, queen, or important official.

Zoom in close to see a scarab beetle rolling a ball of dung. Scarabs can roll balls two or three times their own size.

Idea Two: A nation’s emblem

Chinese Bellflowers and Dragonfly,

about 1830-31,

color woodblock print

Their rich symbolism made dragonflies popular subjects for artists and writers.

In Japan, the dragonfly is a national emblem. In fact, Japan used to be called Akitsushima, or Dragonfly Island. The long, rainy summer season and numerous rivers and streams provide ideal living conditions for dragonflies, which spend the early stages of their life in the water. More than 190 dragonfly species can be found in Japan.

In Japanese culture, the dragonfly has many meanings. It symbolizes the summer season, success, victory, happiness, strength, and courage. Long ago, Japanese farmers believed the presence of dragonflies in their fields meant an abundant rice harvest. Among the samurai, or warrior class, the dragonfly was a favorite emblem for decorating armor and helmets. Throughout the homes of noblemen, dragonfly images appeared in paintings and on porcelain, furniture, and fabrics.

The mythical creature Shoryo Tombo (Dragonfly of the Dead) is associated with the Japanese festival Bon. During this Buddhist festival, people honor their ancestors. The spirits of the dead, carried by Shoryo Tombo, return home to be reunited with their families.

Japan, 1725–70

Reaching for a Dragonfly, 1760s,

Woodblock print (nishiki-e);

ink and color on paper

For many centuries, catching dragonflies was a popular summer pastime among Japanese children. Children had to be creative to catch the quick-moving insect.

Idea Three: A popular pet

Chaing dynasty (1644-1912),

gourd with heat-incised decoration,

ivory, and tortoiseshell

This case contains ten cricket ticklers, used to prompt a cricket’s chirp.

Do you have a pet? Perhaps a dog or a cat? Or maybe a goldfish or a hamster? If you lived in China, you might have a pet cricket. For over a thousand years, the Chinese have kept crickets as pets.

Why keep a cricket as a pet? The Chinese like this insect’s melodic chirping. Beginning in the T’ang dynasty (A.D. 618-907), the Chinese kept crickets in cages in their homes. At night they often placed the cage by the bed, so they could enjoy the crickets’ song. It is thought that the practice of keeping crickets began with women of the imperial palace and was later taken up by peasants, who viewed it as a graceful hobby. During the Sung dynasty (A.D. 960-1279), crickets were prized for their fierce fighting instinct, and cricket fights became a popular entertainment. By the Ming dynasty (A.D. 1368-1644), keeping crickets had become a scholarly pastime, with crickets serving as subjects for poems, stories, and academic research.

A variety of gear was made for crickets and their owners. Molded gourd containers, engraved with intricate designs, kept crickets warm in cold weather. Summertime cages were ceramic or wood. To prompt their crickets to sing, owners used a tickler, made of fine hair or rat whiskers attached to a wood or ceramic handle. Other items helpful in cricket care included feeding trays, cage-cleaning brushes, tweezers, and nets.

Rings such as this were used for cricket fighting matches. The crickets were placed in the ring through the small side doors. Then the wooden divider was lifted, and the match began.

Rings such as this were used for cricket fighting matches. The crickets were placed in the ring through the small side doors. Then the wooden divider was lifted, and the match began.

Idea Four: A word of warning

Still Life with Fruit,

Foliage, and Insects, about 1669,

oil on canvas

Ants crawl over the rotten peaches.

Luscious peaches. Plump grapes. Succulent plums. The Dutch painter Abraham Mignon created a visual feast.

But take a closer look. That fruit isn’t as delectable as it seemed at first glance. In fact, a lot of it is beginning to rot. And the scene is teeming with bugs. Ants are crawling on the peaches. A furry caterpillar creeps along the branch of purple plums near a white butterfly. From behind the striped gourd, a grasshopper peers out. Hidden in the foreground shadows, a black and orange insect climbs onto a piece of broken stonework. Near some acorns in the background, a dozen inchworms dangle in the air or crawl along the branches. And besides all these insects, there are several snails slithering about.

Why would an artist want to include rotting fruit and countless insects in a painting? For Dutch people in the seventeenth century, when this work was made, still-life paintings often had symbolic meaning. The spoiled fruit, damaged leaves, and crumbling architecture all refer to the idea that in time everything must pass away. The caterpillars and butterflies symbolize the life cycle. And many of the other insects are associated with decay. Still lifes that carried this message were known as vanitas (Latin for vanity) paintings. They were especially popular with the middle class in seventeenth-century Holland.

Netherlands, 1640–1679

Still Life with Fruits,

Foliage and Insects, 1669,

Oil on canvas

A small butterfly rests on a branch.

Netherlands, 1640–1679

Still Life with Fruits,

Foliage and Insects, 1669,

Oil on canvas

A small butterfly rests on a branch.

In the shadows, a tiny insect climbs a broken piece of stonework.

Idea Five: A word of warning

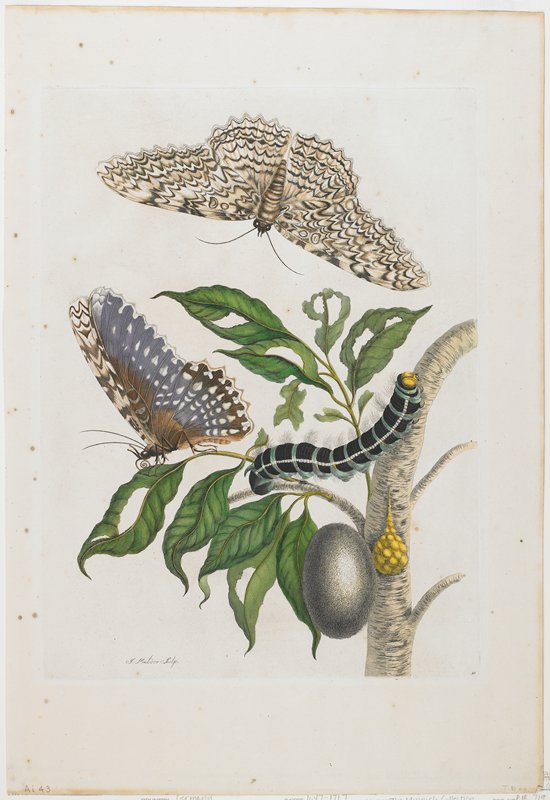

Caterpillar, and Foliage,

from Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, 1705,

hand-colored etching and engraving

In 1699, Maria Sibylla Merian set out for the exotic tropical country of Suriname, a Dutch colony in South America. For two years she studied Suriname’s insects in their natural habitat. She observed their metamorphosis as they developed from egg to adult. She recorded their eating habits and activities, collected specimens, and drew each stage of their life cycles.

Here you see Merian’s study of the four stages of the White Witch moth’s life. First are the eggs, seen in the yellow egg sack attached to the tree. Caterpillars (the second stage) hatch from the eggs. Merian shows one crawling on a branch and eating the leaves. The caterpillar eats voraciously and then spins a silken cocoon around itself (shown next to the eggs). Now it has entered the third stage, called the pupa. The pupa metamorphoses into an adult moth, which then emerges from the cocoon. Merian painted two moths, one in flight and one resting on a leaf with wings folded to reveal the beautiful lavender coloring.

Merian was known both as an entomologist (a scientist who studies insects) and as one of the finest botanical artists of her time. She was taught by her stepfather, a still-life artist, and was greatly influenced by other seventeenth-century Dutch still-life painters. Like them, she paid close attention to detail. Her drawings and watercolors capture every feature of the insects she studied the shimmering silkiness of a cocoon, each bristly hair of a caterpillar, the intricate patterns of a moths wings.

Merian painted over a hundred watercolors during her time in Suriname. When she returned home, sixty of them were reproduced in her book Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium_ (Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname).

A closer look at the egg and cocoon stages.

Merian accurately depicted the segmented body and bristly hairs of the caterpillar.

The moth’s wings are beautifully patterned.

Related Activities

Go Buggy at the MIA

Insects can be found in many works of art at The Minneapolis Institute of Art. Explore the museum and see how many bugs you can find!

Symbolizing the Season

A haiku is a Japanese poem of only three lines. Each line has a set number of syllables: five for the first line, seven for the second, and five for the third. Most haiku are about nature. Often the dragonfly is mentioned, as a symbol of summer. What insect reminds you of summer? Or of another season? Write a haiku and make sure to include that insect.

Out in the Field

Maria Sibylla Merian studied insects in their natural surroundings. Head out to the playground, your backyard, or a local park to see what insects you can find. Then spend some time observing and sketching them.

Become an Entomologist

An entomologist is someone who studies insects. Choose your favorite insect to research. Use your school’s library, the Internet, and other resources to find information on the insect where it lives, its life cycle, what it eats, how big it gets, and so on. Then write an essay, illustrated with a few drawings, to share with your classmates.