Music and art

Colorful sounds abound in these five works of art.

Idea One: Sacred Sounds

Yong Bell (Ceremonial Bell),

late 6th-5th century, BCE,

bronze

This po-cheng bell was probably among the largest in the set it belonged to. When a large bell is struck, it vibrates longer than a smaller bell would, which means its sound lasts longer.

The world’s first bells were produced in China around 3000 BCE. These were ceramic bells, made of hardened clay. Five hundred years later, the Chinese made the first metal bells. Around 1200 BCE, they created the first bronze chime bells. These complex musical instruments were grouped into sets containing bells in a range of sizes.

Bronze bell sets were symbols of prestige, owned only by the ruling elite. Because of the status they gave their owners, such bells were regulated by laws. During China’s Bronze Age (1900-221 BCE), bell music was played in temples during sacred rituals performed as part of elaborate political and religious ceremonies.

To give a bell the desired pitch and tone, the bell maker had to figure out the right size, shape, thickness, and proportions and then cast the bell from a high-quality alloy (mixture of metals). Chinese chime bells had no clapper, or tongue, on the inside. A set of bells was suspended from a wooden frame, and the player struck them with a mallet to make them ring.

This typical yung-cheng bell has an arched bottom, straight sides, cylindrical bosses, and a long shank (yung). When hung by its shank, the bell tilts outward, allowing the player to strike it more accurately. Accuracy was especially important with a yung-cheng bell, which emits one note when struck on the center and a different note if struck on the side.

Ritual Bell,

Eastern Chou dynasty (1027-256 B.C.),

bronze

Bosses not only decorated a bell, they also reduced nonharmonic overtones.

Model of a Yongzheng Bell,

Eastern Chou dynasty,

stoneware

This ceramic model of a Yongzheng bell was placed in a tomb as a substitute for a more expensive bronze bell.

Idea Two: Shall We Dance?

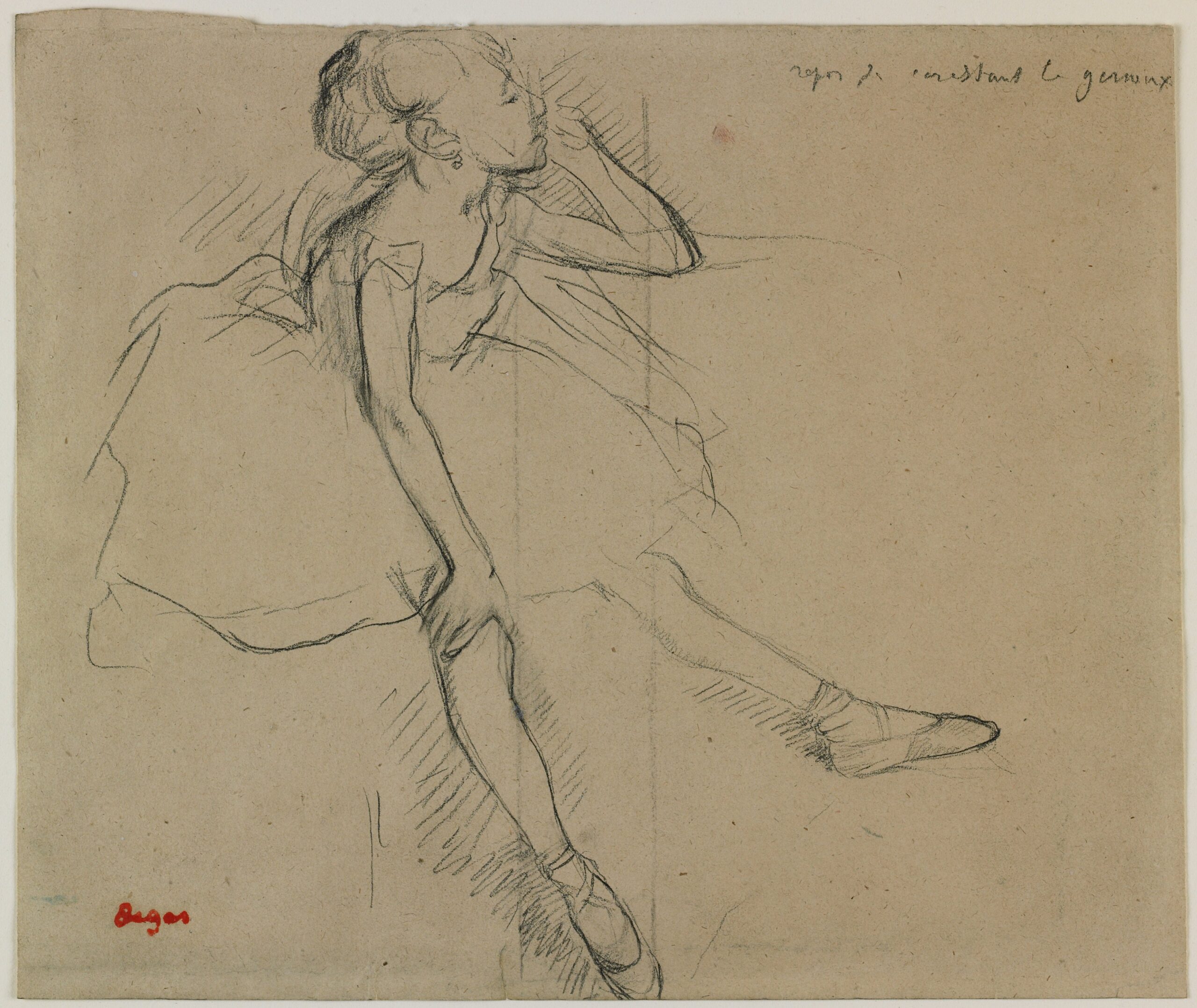

Ballet Dancer in Repos,

about 1880-82,

charcoal on light tan paper

Degas also depicted dancers in his sculptures.

No other artist has painted the ballet like Edgar Degas. Degas captured dancers at nearly every moment, at rest, rehearsing, preparing backstage, performing, and taking curtain calls. All his paintings show his careful observations of the dancers movements, from the various dance positions to the slightest stretch.

Even the youngest dancers (whom he called little rats) caught Degas’s attention. The girl in this drawing was only about eight years old. Her inexperience as a dancer can be seen in the way she sits, slumped over, unaware that the artist is observing her every move.

And Degas sketched every little shift of her body! Even in this small drawing you can see how she moved. Her right arm lightly rubs her knee. Faint outlines show that she moved her left arm several times, stretching it up, then extending it down toward her knee, and finally bringing it up to her face. Quick dashes of line around her back and legs also suggest movement.

It is interesting to know that Degas didn’t start painting dancers because of a great love for the ballet. They call me the painter of dancers, he reportedly said, without understanding that for me the dancer has been the pretext for painting beautiful fabrics and rendering movement. Whatever his motive, Degas will always be associated with the ballet.

Dancer Putting on Her Stocking,

19th century,

bronze

Degas sketched the musicians in the orchestra as well as the dancers onstage.

The Violinist,

about 1879,

charcoal heightened with white chalk on gray paper

Idea Three: The Perfect Player

Orpheus and Eurydice,

1910,

oil on canvas

The love affair between Orpheus and Eurydice was a popular subject for artists.

In Greek mythology, Orpheus was the son of Apollo, god of music and the sun, and Calliope, the muse of poetry. Orpheus played upon the lyre so wonderfully well that all who heard him were charmed. His voice, too, was so beautiful that wild beasts, trees, and even rocks would come near to hear him.

This painting by the artist Maurice Denis shows Orpheus playing his lyre in a forest glade. On his head he wears a laurel wreath, a prize awarded by the ancient Greeks to the best poets and musicians. An audience of nymphs has gathered around him to listen, enraptured by the music, as you can see from their poses. One nymph, Eurydice, kneels with her arms outstretched, transfixed by his song.

Orpheus married the beautiful Eurydice. But shortly afterward, Eurydice stepped on a poisonous snake which bit her, and she died. Distraught with grief, Orpheus traveled to the Underworld to beg for the return of his beloved wife. His song of sorrow caused even the cold-hearted king and queen of the Underworld to weep. They decided to let Eurydice go with her husband on one condition: Orpheus must not look back at her until they both had left the Underworld. The two made the long, arduous journey, but just as Orpheus stepped into the upper world, he looked back. He saw Eurydice for a moment, and then she was gone.

Denis explored the power of music in several of his artworks. He hoped that his harmonious scenes could be heard like music. What do you hear when you look at this painting?

Study for Orpheus and Eurydice,

18th century,

brown ink over graphite on paper

The love affair between Orpheus and Eurydice was a popular subject for artists.

Orpheus Charming the Beasts,

16th century,

pen and brown ink on paper

Orpheus played music that could soothe the wildest beast.

The Wounded Eurydice,

about 1868-1870,

oil on canvas

Eurydice died when a poisonous snake bit her foot.

Idea Four: Musical Messages

Papua New Guinea,

Sepik River Region,

Garamut (Slit Drum),

20th century,

wood

This hand drum, smaller than the garamut, is from the Middle Sepik River region of Papua New Guinea.

The garamut (slit drum) is one of the most important musical instruments in the Sepik River region of Papua New Guinea. It is made from a hollowed-out log and played by striking it with a stick. Men in the community play the garamut at sacred ceremonies, communal celebrations, and dances.

The drum also is used daily for long-distance communication, in a manner similar to Morse code. Drummers have developed a special language of rhythms and notes by which they send messages to other communities. A drum can be used to call people together for meetings, to issue warnings, and to communicate other important information.

This garamut has intricate designs on its handles and body. A carved figure with both animal and human characteristics forms the handles at each end. It also indicates what clan the drum’s owner belongs to. The long, beaklike nose and elaborate hairdo are in a style seen on many objects made in the Lower Sepik River region. The incised and inlaid patterns on the body of the drum are similar to decorations found on shields and hourglass-shaped hand drums from this region.

Papua New Guinea (Iatmul),

Kundu Drum,

20th century, wood

Idea Five: Honoring a Singer

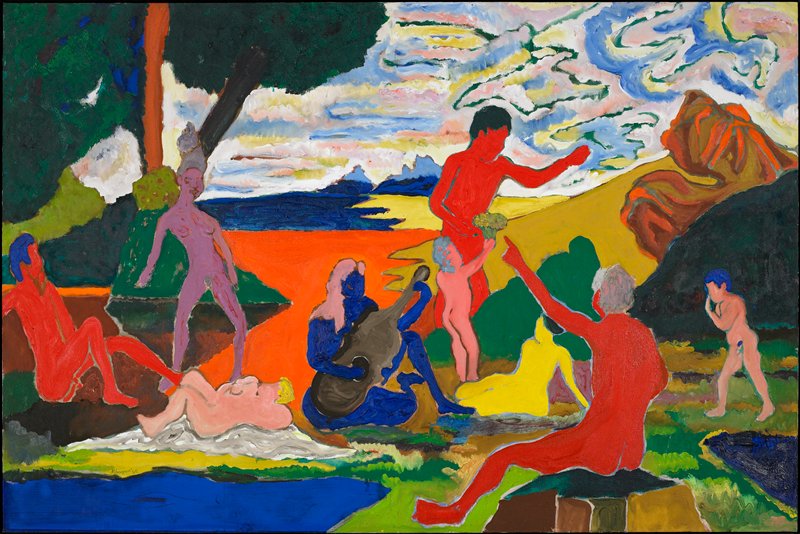

Homage to Nina Simone,

1965,

oil on canvas

The hairstyle helps identify this figure as Nina Simone.

The singer Nina Simone was born in 1933 in North Carolina. Her music was a unique mixture of jazz, soul, blues, folk, and gospel. Simone first found fame in New York, the center of vanguard music during the late 1950s. By the 1960s, she was popular not only for her eclectic sound, but also for her music’s connection to the civil rights movement.

The artist Bob Thompson grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, where he developed a love for music, especially jazz. When he moved to New York in 1959, he became associated with a community of avant-garde musicians, visual artists, and poets. Like jazz musicians, Thompson enjoyed the freedom of improvisation, and he participated in live art performances called happenings.

Thompson spent the summer of 1965 in Provincetown, Massachusetts, with a group of friends and acquaintances that included Simone. Perhaps he was drawn to Simone because of her ability to make a classic song her own. Thompson, too, often borrowed from artists he admired, changing their compositions and infusing them with his own style. For example, he adapted this painting from a 17th-century work called Bacchanale, The Adrians, by the French artist Nicolas Poussin.

In this painting, Thompson celebrates the singer by creating a world of vibrant colors, full of the energy her music must have generated in him. People gather together to relax, dance, and play. In the center sits a blue figure strumming a guitar, and just to the left stands Simone, recognizable by her unique hairstyle.

The Death of Germanicus,

1627,

oil on canvas

Related Activities

Your Homage

Bob Thompson honored Nina Simone in his painting. Who is your favorite musician? Create an artwork that celebrates them. What colors will you use? What setting is right for the musician? Explain your choices in a classroom presentation.

Communication Codes

A garamut drum is used for communication. With a friend, invent your own way to communicate with a musical instrument. Create rhythms that mean help, how are you? and let’s meet after school. Try out this new way of talking to each other.

Extending the Story

Orpheus had to live on after he lost his beloved Eurydice. Make up a story about what happened to him after he returned from the Underworld. Share the story with your classmates.

A Great Discovery

The largest set of Chinese chime bells was found in the tomb of Marquis Yi during an excavation in 1978. Use the Internet and your local library to research the discovery.

Bibliography for Kids

Anholt, Laurence. Degas and the Little Dancer. New York: Frances Lincoln Publishers, 2003.

Merberg, Julie and Bober, Suzanne. Dancing with Degas. New York: Chronicle Books, 2003.

Schonfeldt, Sybil Grafin. Orpheus and Eurydice. Los Angeles: Getty Trust Publication: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001.