Surrealism

See what happens when artists set out to change our view of reality.

Idea One: Don’t be so reasonable…

Through Birds, Through Fire but Not Through Glass, 1943

Oil on canvas

In 1924, the French poet André Breton (on-dray breh-TOHN) called on writers and artists to explore a world beyond everyday reality. This was the beginning of Surrealism (from the French for beyond real), a movement that influenced many artists in the 1920s and 1930s. In this picture, Yves Tanguy (eev ton-GHEE) used a clean, crisp style to paint weirdly lifelike shapes set in an eerie landscape. But the Surrealists did not set out to imagine a fantasy world. Their goal was to present a view of the unconscious mind.

The concept of the unconscious was new at the time. The psychologist Sigmund Freud (froyd) had recently described mental life as a conflict between the civilized, thinking mind and inner desires we are not normally aware of. Freud thought that understanding this conflict could help cure mental illness. The Surrealists, on the other hand, hoped to bypass the thinking mind completely. They wanted to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, free from the control of reason, morality, or good taste.

It has been said that Tanguy painted like a sleepwalker. He did not try to explain the mysterious images he produced. Often he let his friends suggest puzzling titles. For example, this picture is called Through Birds, through Fire but Not through Glass. For the Surrealists, explaining an image was just one more way for the thinking mind to control the unconscious.

Idea Two: A window into the mind

the Assistant to Velázquez,

1960,

oil on canvas

Max Ernst often used collage to create dreamlike scenes by combining parts of different images in unlikely ways.

Hidden from awareness, the unconscious mind is hard to know. The best chance comes in sleep, hypnosis, or madness. Yet the images in our dreams, trances, or delusions are still only symbols of unconscious meanings. Freud believed these symbols could be interpreted to reveal underlying fears and desires. The Surrealists, however, were more interested in the images poetic surprises.

Some Surrealist pictures suggest images from dreams or trances. As in dreams, unrelated objects and events combine in a matter-of-fact way, often in a strange, confusing space. Such pictures can be disturbing or shocking. Here, Salvador Dalí (SAHL-va-dor DAH-lee) presents a dizzying scene of flying nails, open gashes, and haunting figures from famous 17th-century paintings.

The Surrealists occasionally tried out ways to bring on sleep and hypnosis, even madness, for the purpose of making art. But some of them argued that pictures based on dreams or hallucinations could never be a true record of the unconscious. They had, after all, passed through the filter of memory.

plate from the book Une Semaine de Bonté, 1934,

photoengraved collage

The ghostly figures of this picture are surrounded by symbols of fertility and birth.

Idea Three: It looks so real!

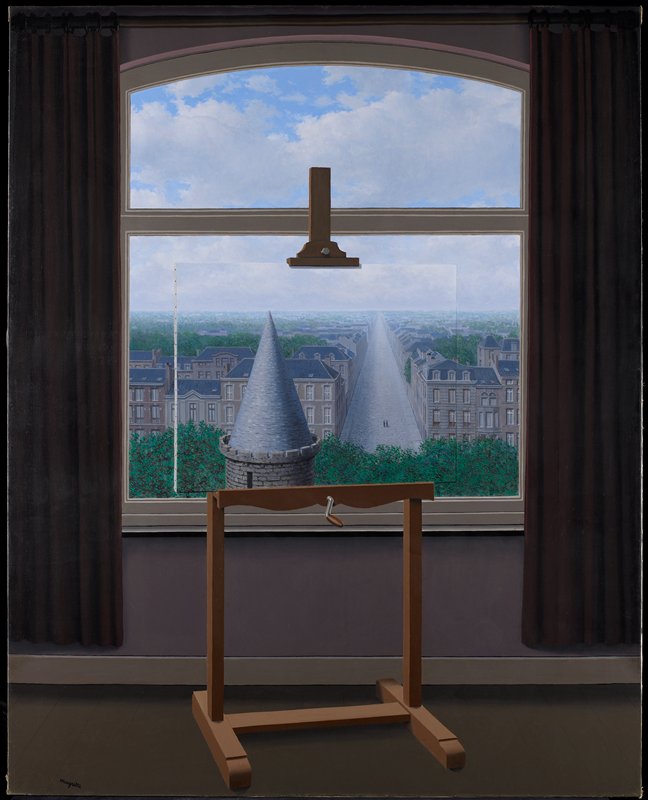

Promenades of Euclid, 1955

Oil on canvas

Even imaginary forms can be painted in a realistic manner.

The eye is a friend of the conscious mind, seeing is believing, as the saying goes. Some Surrealists painted fantastic scenes in a crisp and clear style meant to make their visions seem believable and real.

René Magritte (ruh-nay muh-GREET) did not share the Surrealists interest in dreams. Instead, he liked to present easily recognized, everyday objects in puzzling situations. He insisted that his paintings, unlike dreams, had no symbolic meaning. He simply intended to confuse the rational mind, through surprise and mystery. Here, for example, it’s hard to say whether the street scene actually exists outside the window or is painted on the canvas held up by the easel. Magritte hoped this sense of mystery would make people question their experience of the ordinary world.

Reply to Red, 1943,

oil on canvas

Idea Four: Art by accident

Head of a Woman, 1938

Oil on canvas

Laboring over a picture, especially a realistic picture, struck some Surrealists as contrary to their goals. When an artist tried to give form to the unconscious, the very act of painting added a layer of thought. How could art-making become more spontaneous?

Writers used free association and simply wrote down words that occurred to them. Or they cut out words from the newspaper, shook them up in a bag, and pulled them out one by one to form poems. Visual artists came up with their own automatic techniques, based on chance or accident. The painter Max Ernst created images by rubbing a crayon across paper pressed down on a rough surface. Man Ray made photographs without a camera, by laying objects directly on the photographic paper.

Joan Miró (zjo-AHN mee-RO) had an interest in such automatic processes. He started his pictures with aimless doodles and let images develop from the doodles. In the act of painting, a shape will begin to mean woman, or bird . . . , he said. The first stage is free, unconscious. This figure of a frantic, ghastly woman gives form to Miró’s feelings about the civil war just starting in his native Spain.

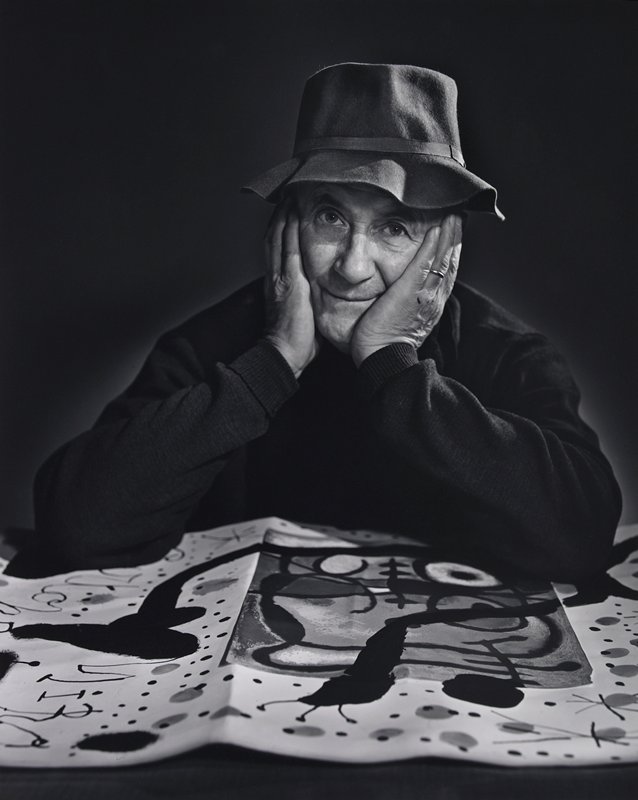

Joan Miró,

1965,

photograph

Joan Miró developed his characteristic style based on automatic techniques of Surrealism.

. . . istan/islam, 1924,

gelatin silver print rayograph

Man Ray invented the rayograph, an image made by placing objects directly on photographic paper and exposing it to light.

Idea Five: A shock to the system

Aphrodisiac Telephone, 1938

Plastic, metal

Though not a Surrealist himself, the painter Balthus was a friend of many Surrealists and shared their interest in the workings of the unconscious mind.

The Surrealists viewed morality and good taste as part of rational thinking. Art that bypassed those filters would, at times, be shocking. Shocks were useful, because they disrupted conscious thought. When the conscious mind is too shocked to think, the unconscious is more clearly revealed.

To make this sculpture, Salvador Dalí took a telephone, an ordinary household object, and replaced the receiver with a similarly shaped model of a lobster. Imagine absentmindedly answering the telephone and feeling a lobster clawing at your head!

But Surrealist shocks did not have to be disturbing. A lobster-telephone is also funny. The Surrealists used unexpected combinations like this to shake people up and get them to see the world differently.

The Living Room, 1941-43,

oil on canvas

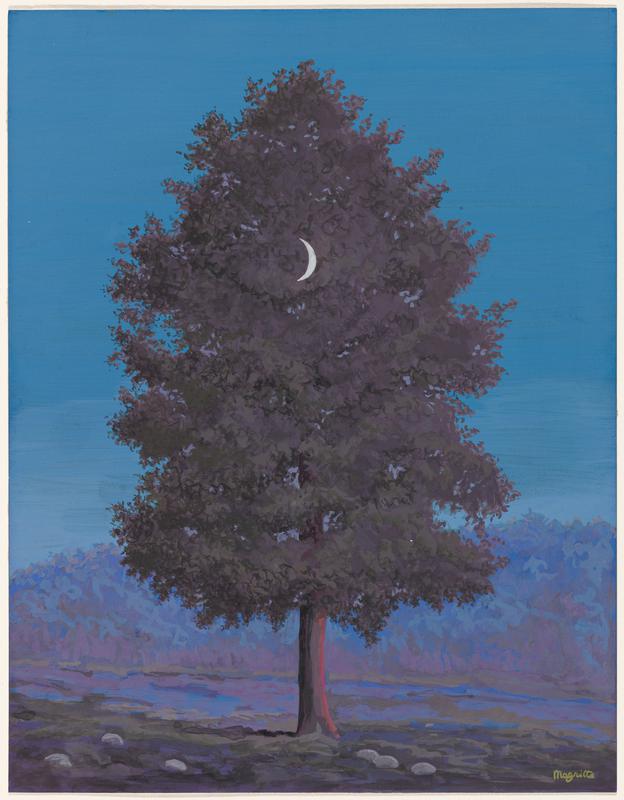

Le 16 Septembre (Tree with Crescent Moon),

about 1955,

gouache on paper

This picture gives the logical mind a quiet surprise, the moon is in front of the tree instead of behind it.

Related Activities

Exquisite Corpse

The Surrealists enjoyed the poetic effects of chance combinations in a game called Exquisite Corpse. To play, form a group of four to six people. Cut blank sheets of paper in half lengthwise and give every player one of the half-sheets. Each person writes a few words at the top and folds the paper down just far enough to hide the writing. The papers are passed along to the next person, who adds some words without seeing what came before, and folds the paper down again. When the papers have gone around the circle, and everyone has written something on each one, open them all up and read the resulting poems.

The Interpretation of Dreams

Keep a dream journal for a week. Then learn more about Freud’s theories of dreams and the unconscious. (Two good sources are On Dreams by Sigmund Freud and The Secret Language of Dreams: A Visual Key to Dreams and Their Meanings by David Fontana.) Does anything you read seem to apply to the dreams you recorded in your journal?

Dream Worlds

Create a dreamlike scene by cutting up pictures from newspapers or magazines and gluing them together in startling combinations. Then use this collage as the basis of a painting or drawing that unifies the parts into a single image.