The Art of Realism

What’s real? See for yourself how five artists represent the reality of their – or other – worlds.

Idea One: The Delight of Deception

Italian, 1460–1500

Madonna and Child Enthroned, c. 1490

Tempera and oil on panel

The John R. Van Derlip Fund.

Has a painting ever played tricks on your eyes?

When art looks really real, it is called _trompe l’oeil_, a French term meaning “fool the eye.” This Christian painting of Mary and baby Jesus contains a great example of _trompe l’oeil_: check out the fly near the foot of Mary’s throne. It looks so real, it’s tempting to brush it off the canvas!

How do you think the artist created this effect using paint?

Nicola di Maestro Antonio carefully selected his colors to create texture. He used perspective, a method of combining lines to create the illusion of depth, and also carefully painted shadows to give the figures a 3-D effect. Artists like di Antonio enjoyed painting beautiful pictures that viewers could experience both visually and emotionally. They believed people could feel more connected to paintings that looked realistic.

Di Antonio painted during the early Renaissance, a period of cultural rebirth in Europe. European artists began to use ancient Greek and Roman art as inspiration for their own artwork. They liked how ancient artists portrayed natural-looking people and objects. Even though figures were often idealized, they were dramatic, emotional, and humanlike.

The still life at the bottom of this painting may look realistic, but it also contains hidden meanings. Renaissance artists often put symbols, or iconography, into their art. The fly stands for evil, while the gourds stand for its antidote. The coral necklace around baby Jesus’s neck was a charm against evil.

This painting is an allegory, containing symbols that have deeper meanings. The pots and pans represent the four elements: fire, water, earth, and air.

René Magritte, 1962

Etching

Gift of Martin Weinstein in memory of Joseph A. Weinstein

This etching was inspired by Magritte’s earlier painting, La Trahison des images, which featured a realistic-looking pipe and a caption that read “This is not a pipe.” Magritte reminds the viewer that, no matter how realistic an image looks, it’s not actually real.

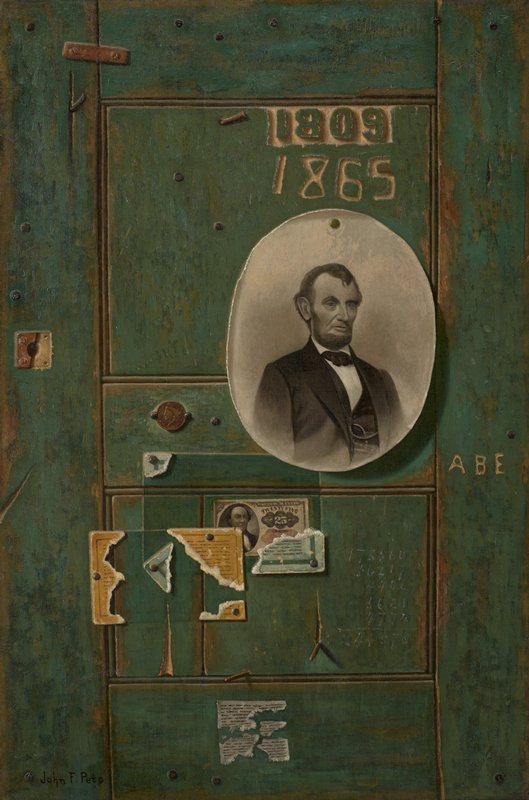

John Frederick Peto was skilled at painting _trompe l’oeil_ illusions. It’s hard to believe this is a painting—not a carved door.

American, 1854–1907

Reminiscence of 1865, after 1900. Oil on canvas

The Julia B. Bigelow Fund by John Bigelow

Idea Two: How Real?

French, 1819–77

Chateau d’Ornans, 1855

Oil on canvas

The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

Gustave Courbet painted this scene of the French countryside during a period in which people in France expected art to depict a perfect world, much prettier than the one they lived in. But Courbet believed that art should be truthful and depict the actual world, dirt and all. Courbet called himself a “painter of the real,” vowing only to paint what he could see. He believed that art had the power to teach people lessons, or even criticize society.

This painting is of Ornans, the town where Courbet grew up. On the surface the scene is serene. But it also has a revolutionary hidden meaning. The houses on the hill sit atop the ruins of an old castle destroyed by the French government in the 1600s to prevent the provinces from organizing together to take power away from the monarchy. The village built on the ruins represents how the peasants of Courbet’s time were able to thrive over past oppression. Courbet celebrated the everyday lives of the working class in his art; he shows a woman doing laundry in the foreground of this picture.

Courbet’s painting not only depicts the real world, but it also actually includes it. Look closely at the painting. How would you describe the texture?

If it looks gritty and bumpy, it’s because Courbet actually mixed his paint with dirt from the valley. By mixing in dirt, he made the painting that much more real. In fact, his painting style offended the art critics because it was so unrefined. The ruggedness of the painted surface reflects the tough lives of the peasants. The dirt also reminds us of nature’s power in connecting our past, present, and future.

Winslow Homer was an American painter who depicted the world as he saw it. While Realism was a controversial movement in France, it was a traditional style for American artists. Paintings like this one allowed Americans to see worlds about which they may never have known.

The Ife (ee-fay) culture of Nigeria had a rich tradition of realist sculpture dating back to 1050 CE. Portrait heads like this one show careful attention to the details of facial features, including the pattern of scarification.

This closeup shows just how gritty the texture of this painting really is.

Gustave Courbet, French, 1819–77. _Chateau d’Ornans_ (detail), 1855. Oil on canvas. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

Idea Three: Artistic Role Playing

Japanese, 1725–70

Mitate of the ‘Hachinoki’ Story, 1765–66

Color woodblock print

Gift of Louis W. Hill, Jr.

What seems to be going on in this picture?

This Japanese woodblock print is called a mitate. Mitate are visual puns or similes. They depict scenes from famous stories, plays, or parables, but with a twist: the artist often placed famous people, iconic settings, or beautiful women into the scene, creating a fantasy print that still contained elements of reality. Because mitate often referenced theater, literature, or religious stories, they were a sort of intellectual game. Viewers enjoyed identifying the people and stories in the prints.

One of the most popular types of mitate depicted beautiful women playing the roles of men from famous plays or stories. This image, created by Suzuki Harunobu, an artist who specialized in mitate, shows a scene from a well-known play from the no theatre called Hachi-no-ki (Potted Tree). The play is about an impoverished samurai who offered to burn his last three bonsai trees to keep a traveling monk warm on a cold winter night. The monk, who was really a government official in disguise, was so pleased with the samurai’s sacrifice that he rewarded the samurai with three tracts of land. Each piece of land was named for the sacrificed trees: pine, plum, and cherry. In this print, Harunobu replaces the poor samurai with a well-dressed, charming woman. She is about to daintily chop into the first tree.

Even though this print is a fantasy, Harunobu made it look believable. Describe the visual elements and details he included to make the scene look so real to his audience. For example, think about the props, sense of space, and the setting.

An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo, 2001

Color photograph on canvas.

Gift of funds from Beverly Grossman. © 2001 Yasumasa Morimura, courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

This is a photographic reenactment of Spanish painter Francisco de Goya’s etching, _The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters_. Yinka Shonibare substituted a real person wearing colorful Dutch wax cotton for Goya’s original figure. Yinka Shonibare, English, born 1962. _The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Australia)_, 2008. Chromogenic print mounted on aluminum. The C. Curtis Dunnavan Fund for Contemporary Art. © Yinka Shonibare, courtesy James Cohan Gallery, New York.

Dutch, 1606–69

Lucretia, 1666. Oil on canvas

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

Yasumasa Morimura recreates famous portraits using his own face and body as the subject. Here, he stands in for the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. He wears fabric designed by Louis Vuitton and a Japanese-style hair ornament.

Rembrandt used Hendrijke Stoffels, the love of his life, as a model for this realistic painting of a Roman story about Lucretia, a woman who took her life rather than live in dishonor.

Idea Four: Re-presenting Art: Copies and Reproductions

American, 1783–1872

_Portrait of George Washington_, (1732–1799), c. 1820

Oil on canvas

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

This portrait of George Washington is actually a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s iconic _Landsdowne Portrait_, originally completed in 1796. Stuart’s portrait of Washington proved so popular, many banks, civic buildings, and museums requested copies of the painting. With Stuart’s permission, Thomas Sully began painting replicas because Stuart could not fill the orders by himself.

Both Stuart’s and Sully’s portraits depict Washington as a hero. Washington, the nation’s first president, helped unify and lead the new country, even in the face of political disagreements and foreign threats. Both paintings show Washington’s strong nature through his physical stance, in addition to subtle icons; his sword, for instance, represents his military background, while his simple black suit shows him to be one of “the people,” instead of a privileged and out-of-touch monarch.

The two portraits are very similar, but not exact. While Stuart’s portrait shows Washington holding out his hand, Sully placed Washington’s hand on the Constitution, symbolizing his connection to this important document.

Compare Sully’s portrait to the original painting at the National Gallery to see what other differences you can find.

Do you think Sully’s copy of Stuart’s painting has its own artistic value? Why or why not?

Is this copy worthy of being in a museum? What makes you say that?

Do you think this painting is important because it re-presents an iconic painting, or does it have merit on its own as a well-produced artwork?

This is essentially a miniature museum of selected works by artist Marcel Duchamp. Beginning in 1936, Duchamp began making miniature reproductions of his own artwork. He made 350 of these miniature museums. Marcel Duchamp, American (born France), 1887–1968. _Boite-en-Valise_ (Box in a suitcase), conceived 1936–1941; assembled 1961. Linen-covered box containing mixed media assemblage/collage of miniature replicas, photographs, and color reproductions of works by Duchamp. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp.

The Doryphoros is a Roman copy of an original Greek bronze statue. About four remain in the world. It’s considered a precious work of art in spite of being a copy. What do you think gives the Doryphoros its value?

Idea Five: Realism out of this World

Funerary Model of a Pig Sty

2nd century BCE

Ceramic, earthenware

Gift of Alan and Dena Naylor in memory of Thomas E. Leary.

In China, during the Eastern Han dynasty (25 BCE–220 CE), it was customary for people to furnish the tombs of loved ones with ceramic figures, called ming-ch’i, that depicted everyday people, places, and things from the living world. The idea was to recreate the comfort and familiarity of this world in the afterlife. They believed that the contents of the tomb should reflect the deceased’s life so he or she could continue living comfortably in the afterlife.

Ming-ch’i grew even more popular during the T’ang dynasty (7th–8th century CE) when funerals became extravagant festivals. In 742 CE, the government issued an edict that established how many ming-ch’i people could place in tombs. The number and quality corresponded to a person’s social rank and wealth. While notable people were allowed up to 70 pieces, commoners were only allowed about 15.

The person who crafted this model included realistic details of an actual Chinese style pigsty, including piglets, feeding containers—even toilets (located under the roof)!

Look closely at the scene. Describe the everyday details that you see. What can you learn about ancient Chinese culture from this artistic interpretation? What kind of person do you think this set was created for? What makes you say that?

Egypt,

22nd-18th century BCE,

Polychromed wood,

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

This boat was placed in an Egyptian noble’s tomb to help transport his or her soul to the next life. It is a miniature replica of the boats Egyptians used for fishing and transportation in their daily lives. Egypt, Model Boat and Figures, Middle Kingdom (22nd–18th century BCE). Polychromed wood. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

Japan,

6th Century,

Ceramic,

The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund

Ceramic figurines, called haniwa, accompanied deceased Japanese aristocrats in their tombs. They may have been thought to provide protection, comfort, and service in the afterlife. Notice the realistic details of her necklace, hairdo, and medicine bag. Japan (Kofun), Haniwa Figure, 6th century. Earthenware. The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund.

Moche,

1st-2nd century,

Ceramic,

The William Hood Dunwoody Fund

Moche, Peru, Andean Region. Vessel, ceramic, pigment, 1st–2nd century. William Hood Dunwoody Fund.

An ancient Peruvian civilization called Moche created pottery that faithfully reflected everyday life, such as this prominent couple feasting on seafood. Vessels like this would have accompanied elite people to their tombs, carrying on their status and serving in the afterlife.

Related Activities

Hidden messages

An allegory is a creative way of expressing a hidden meaning, like a code. Allegories are often communicated through realistic and familiar images. For instance, sometimes movies use rain to symbolize sadness. Create your own allegory. Be creative—you can write, draw, or even build an allegory out of found objects. Ask your friends and family if they can figure out the meaning of your allegory.

It’s your (casting) call

Who would you like to see playing a character from your favorite story, movie, or even artwork? Create a drawing, poster, or woodblock-style print in which you substitute a friend, family member, pet, or cartoon character for this character. Use your imagination! Sponge Bob could become Cinderella, or your best friend could become Spider Man!

Discussion: Grounding Fantasy in Reality

What is it that makes a fantasy more believable? Think about movies like _Harry Potter_ and _The Avengers_. What do movies need to include in order to be considered believable? Why do you think they need to include these elements? Do you think cartoons can be believable? Why or why not?

Tombs and Time Capsules

Ancient tombs are like time capsules; they preserve some of the most important objects—including artwork—from the past. Such objects teach us a lot about the everyday lives and beliefs of ancient people. Design your own time capsule by drawing or crafting your objects from clay. What objects would you include to represent the important things in your life? Why did you include these objects? What might they say to future people about who you are and how you lived?

Fact vs. fiction

Pretend you’re an archaeologist. Use the search function on Mia’s website or visit the museum in person to create a “collection” of 3-5 objects from the same culture. Try to learn as much as you can about the works, then write a history about them. Talk about who created them, who may have used them, how they were used, when they were made, and what they are. But here’s the twist: Invent fake stories for 1-2 of the objects. Then present to your class, and see if your classmates can tell fact from fiction. Discuss as a class: Can you always believe what you hear? How do you separate fact from fiction? Why is this an important skill to have?

Realism for sale!

Advertisers often use realistic-looking, yet idealized, images to convince people to buy their products. Pick three advertisements in different media (television, magazines, websites, billboards, etc.) that use realistic images. Write a description for each ad. Then write a response to the following statements:

1.This advertising image is realistic because. . .

2.This advertising image is unrealistic because . . .

3.Write whether you believe the ad will be successful at selling the product. Be sure to explain why or why not.

Then discuss your essay with your classmates.