100 Years After Receiving It, Mia Conserves a Late Gothic Manuscript

By Alex Bortolot, with contributions from Sherelyn Ogden and Rachel McGarry

January 12, 2022—In 1921, the collector Herschel V. Jones gave Mia an antiphonary, a manuscript of sung portions of the Christian Mass and the Divine Office, known as antiphons. It was created in 1439 and used by a community of nuns at the Congregation of Fontissalientis in northwestern Germany, as a cycle of daily devotions. Placed on a lectern, it would be opened throughout the day to certain prayers and performed, in a call and response between cantor and choir. (Listen here to a male choir perform passages of a fifteenth century Venetian antiphonary, currently in the Special Collections Library at the University of Michigan.)

Jones was an important early collector in Minneapolis of rare books, prints, and drawings. His 1916 gift to Mia of 5,300 prints established the museum’s esteemed print collection; subsequent gifts included some of the museum’s most treasured Old Master prints. The antiphonary is no less remarkable. Many other examples have been disassembled by dealers or collectors so their pages, or leaves, could be sold individually—a process called “book breaking.” Mia has many such sheets in its collections, beautiful but akin to orphans, lacking context. This German antiphonary is the same today (if more worn) as the day it was created, its 270 hand-lettered leaves held snug and safe within a protective binding of wood, leather, and metal for nearly 600 years.

The blind-tooled leather binding, leather straps, and metal clasps are original to the manuscript, and it is largely thanks to them that this antiphonary has remained in one piece. Bindings and coverings evolved to keep a manuscript’s contents safe yet accessible. On the one hand, they were a book’s protective armor, strong and durable, substantial enough to support its formidable size and weight. On the other hand, they had to be light and flexible enough for the book to remain portable and easily opened and consulted.

To meet these somewhat competing demands, book binders perfected complex binding structures using materials whose properties, in combination, served to protect, adorn, and provide access to the contents. First, the leaves of the manuscript were stacked in order and sewn together to supporting thongs. These were then laced into thin wooden boards of oak, beech, or poplar, which formed the front and back covers.

Fully assembled, the bound manuscript’s covers and spine were clad in leather and finished with decorative tooled designs and protective hardware including corner plates, studs and bosses, and clasps. (For more detailed information on medieval bookbinding, including drawings and diagrams, visit this online booklet prepared by the Special Collections Conservation Unit of the Preservation Department of Yale University Library.)

Mia’s antiphonary had been exhibited a number of times over the past century and studied by scholars, but by 2020 it had become almost too fragile to open or move. The binding was torn through the headcap and split at the center of the spine, making the book vulnerable to further damage. The brittle leather spine could split, tear, and disintegrate beyond repair.

Associate Curator Rachel McGarry, weighing the museum’s countless conservation projects, felt this object was among the most urgent. “It’s an intact example, and exceptionally old. It’s our job to preserve it,” she says. Furthermore, the pages were dirty from centuries of use, and would benefit from light surface cleaning, improving the antiphonary’s appearance while preserving its signs of age. Conservation of the binding would stabilize the tears and cracks, making it safe to open for display while also revealing how the binding was made.

Through the generous support from the Blackman-Helseth Foundation, Mia engaged St. Paul-based conservator Sherelyn Ogden, who made the following enhancements to ensure the antiphonary remains a viable object of display and study (photos are courtesy of Sherelyn Ogden Preservation Associates).

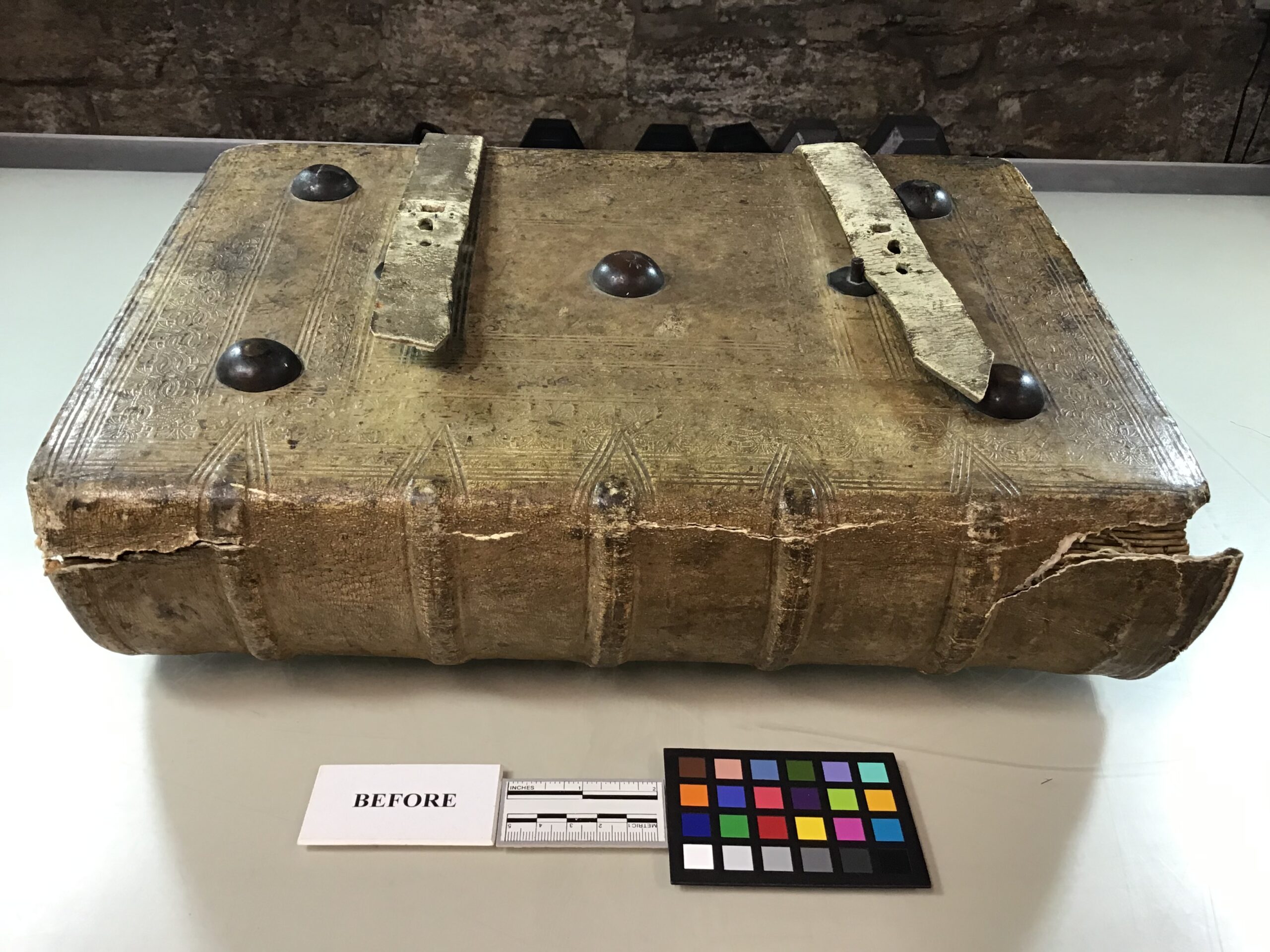

This image shows the damaged binding before conservation. Underneath the five raised bands on the spine are the supporting thongs that connect the sewn leaves of the manuscript to the wooden covers.

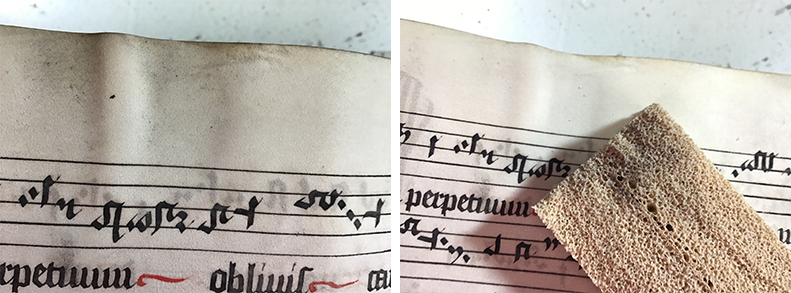

Here is the same page before and after cleaning. The leaves of the antiphonary are made of vellum (thin calfskin); the lettering is rendered in red, black, and blue ink. A layer of grime on the leaves’ surfaces and edges made them dull and detracted from an observer’s visual appreciation of the calligrapher’s skill.

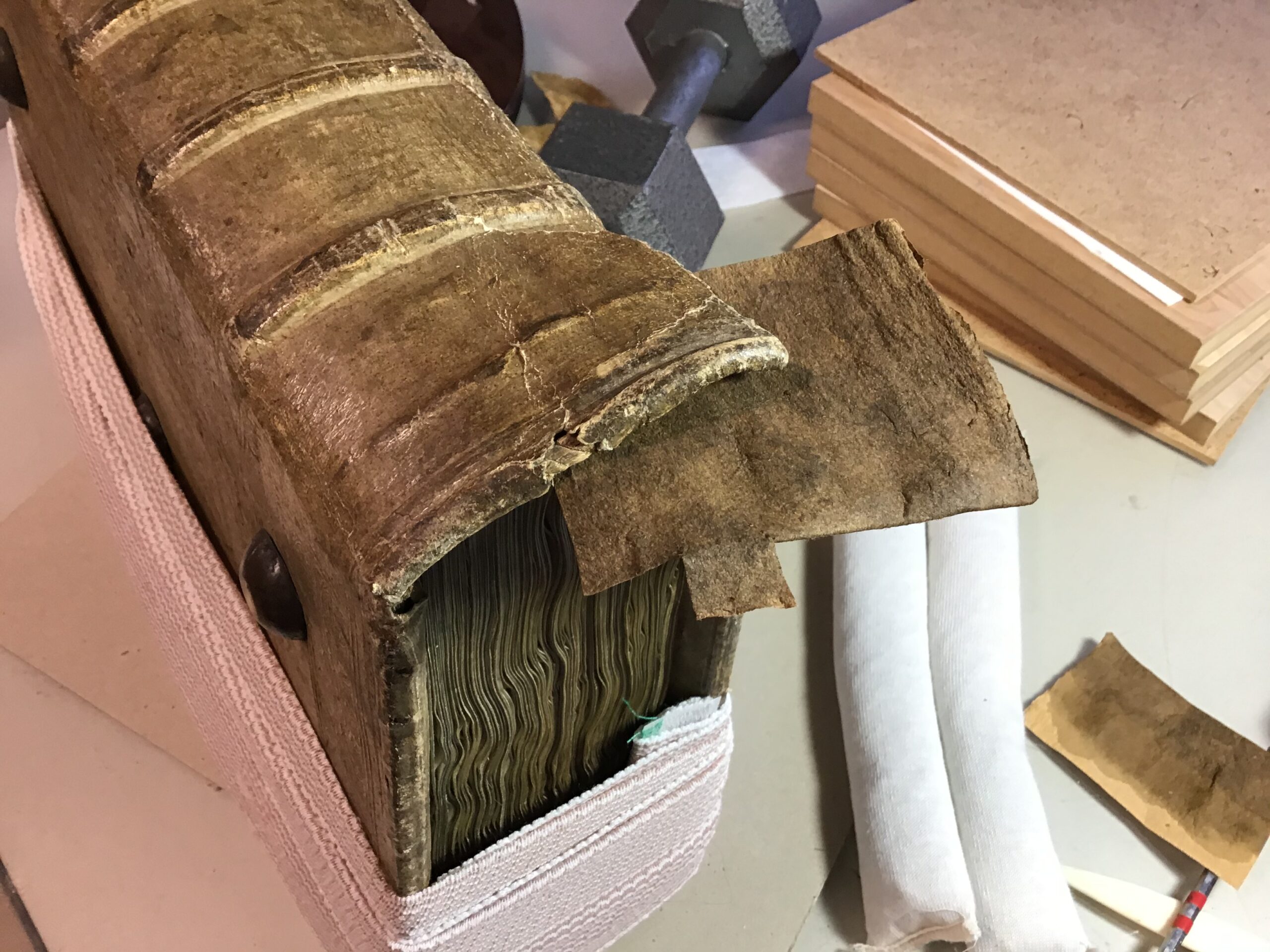

Repair paper, dyed to match the leather binding, was inserted beneath the torn leather and adhered in place to stabilize these areas and prevent further tearing and cracking.

The ends of the binding (called the endcaps) were torn, missing leather, and structurally damaged. Ogden adhered repair paper made of linen, its long fibers both tough and flexible, to the undersides of the torn leather and then bandaged the book to maintain pressure while the adhesive was drying.

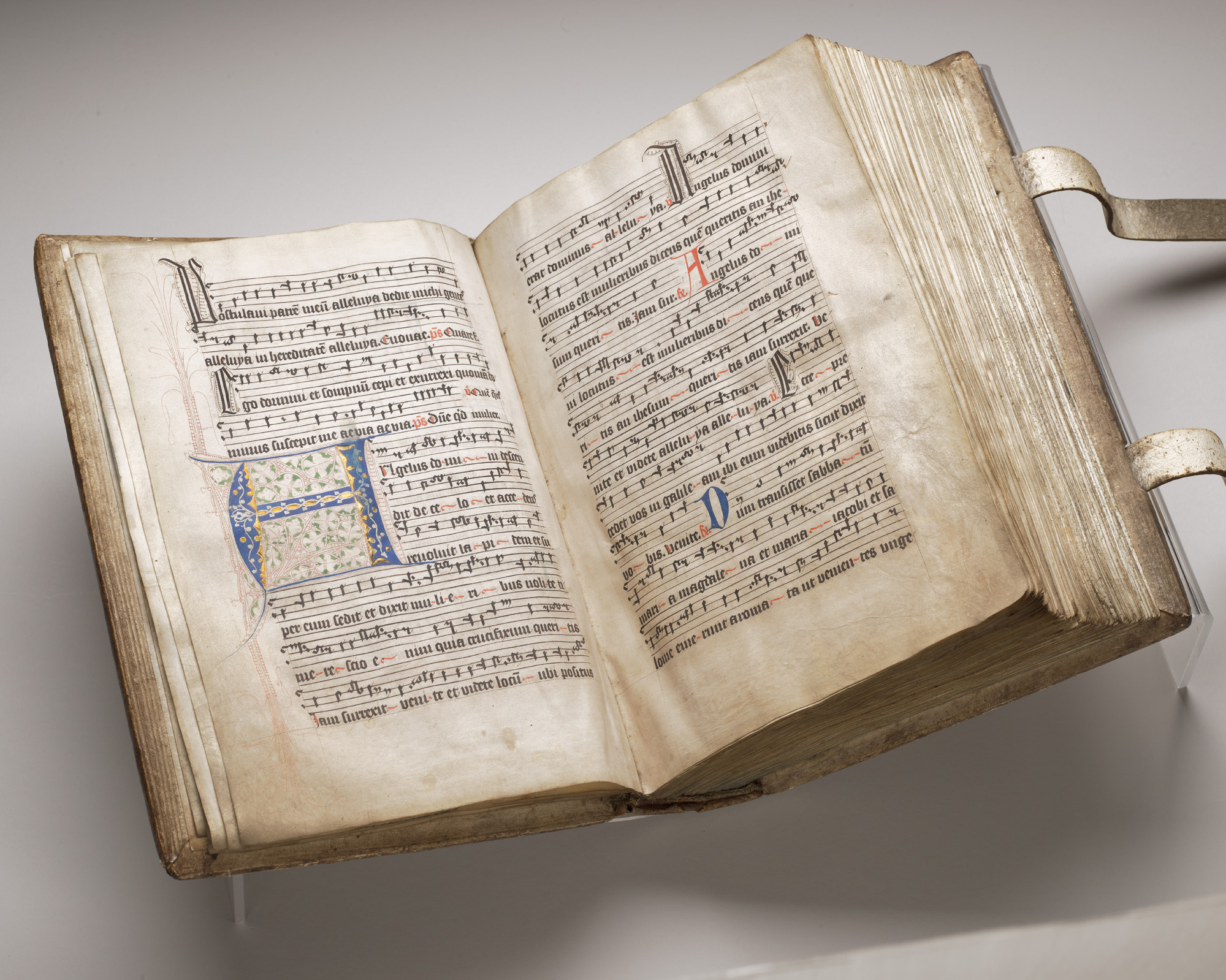

After conservation and cleaning, the antiphonary’s cracks and tears are stabilized. The layer of grime is removed, retaining the patina of age and use while also revealing the beauty and complexity of the binding and its tooled decoration.

The antiphonary also received a clamshell book box, custom made by Minneapolis-based restorer Dennis Ruud. Clamshells provide an additional layer of protection when the manuscript rests in storage.