By Ian Karp

In 1988, after a life of relocation, the punk artist, writer, teacher, activist, and squatter Fly Orr—known as Fly—landed on New York City’s Lower East Side. Soon after, she moved into an East Village squat (an illegally occupied building, usually neglected, vacant, or abandoned) and became involved with the community art space ABC No Rio, a center for performance and squatter arts and activism. There, Fly dove into countercultural scenes on the Lower East Side, surrounded by other musicians, artists, activists, and squatters.

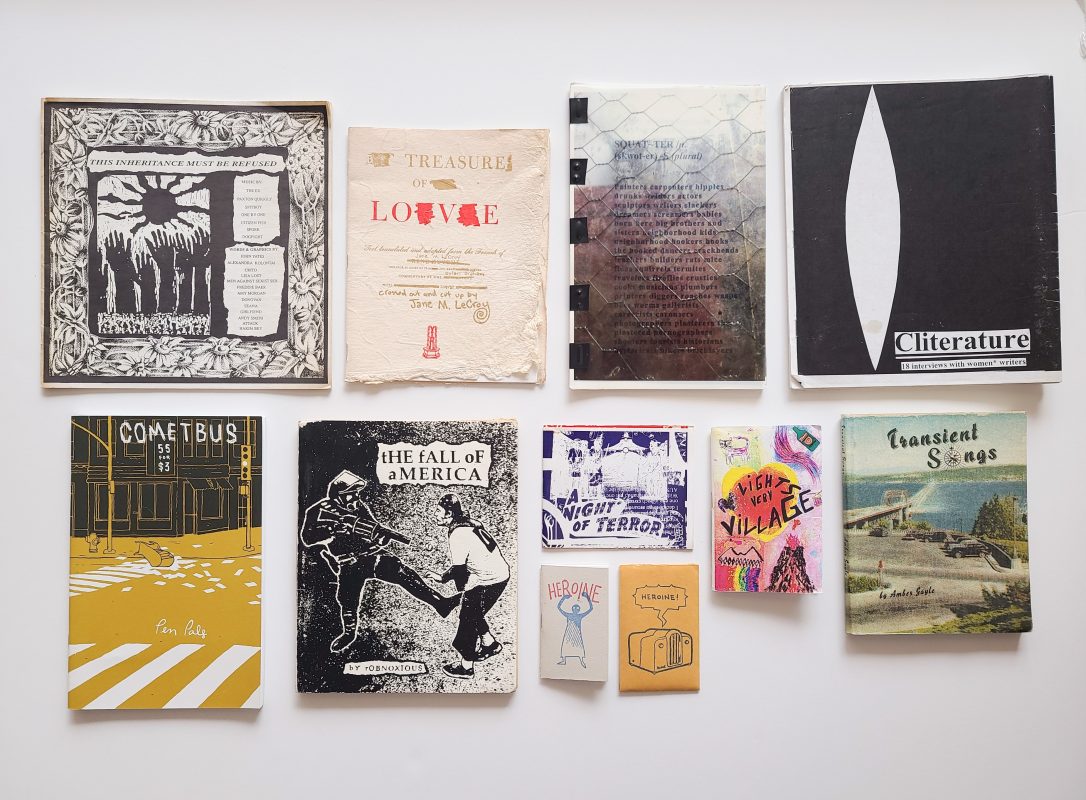

In addition to her work as a comics illustrator, muralist, and squatter activist, Fly was an archivist, collecting printed matter and other artwork that circulated in the underground communities she had been part of since the mid-1980s. After 35 years of accumulation, Fly’s collection had grown to more than 1,900 art objects from around the world, spanning the 1980s to the present. Fly’s collection consists mostly of zines, a type of self-produced publication that has long connected the various strands of the underground. It became known as the Fly Zine Archive (FZA).

Kate Huh, “Rebel Fux!” #22, 1996-2001. 2018.86.1513. Fly Zine Archive, The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books and gift of funds from Mary and Bob Mersky.

Mia recently acquired the FZA, making it the first major museum to add a zine archive to its permanent collection. Highlights of the archive are now on view in Gallery 315.

The FZA’s diverse array of counterculture publications and art offers Mia visitors the opportunity to learn about a range of topics historically discounted by museums, namely artist and activist work within punk, squatter, feminist, and anarchist communities. In addition to zines, the archive includes comics, drawings, prints, punk rock show bills, DIY guides, poetry collections, neighborhood newspapers, artists’ books, and more than 150 issues of the punk periodical Maximum Rocknroll. It’s rich in contributions from LGBTQ+, Latinx, and unsheltered artists and writers, as well as activists in areas like mental health, safe drug use, affordable housing, and systemic police misconduct.

Fly created and collaborated on some of the archive’s contents herself. She picked up and traded for other material at countless zine and anarchist book fairs, neighborhood meetings, and punk shows, both in New York City and on tour. The collection also grew with zines and comics that Fly received in the mail. Exchange through the postal system had evolved naturally within the zine community, as a way to self-distribute media and to connect with fellow artists, writers, and zinesters. Fly received material from San Francisco’s East Bay punk scene and Vancouver squats, as well as from France, Italy, the Netherlands, Japan, and elsewhere.

While the FZA contains a wide variety of artwork and publication, it is the spirit of DIY that drives the collection as a whole, an ethic embodied by the zine medium regardless of subject matter. There is no formal specificity to the medium, although the typical zine is a printed copy of a collaged master that comprises both original and appropriated media. Compositions include handwritten and word-processed text as well as illustration, photography and other graphic artwork. Some zines are printed using high-end printers, such as the Risograph, a stencil duplicator that allows for accurate multiples to be printed in several colors. More often, zines are black and white, xerographic copies made with a standard office copier, giving them that rough reproductive haze we all know.

Mission Mini Comix, composite of 4 minicomics: “Happy Bunny Gets V.D.,” “Lil’ Dope Fiend Overdose Prevention Guide,” “Separation of Corporation & State,” and “Why Use Reason When You Can Use Pepper Spray!,” 2011-2013. 2018.86.1419, 2018.86.1428, 2018.86.1429, and 2018.86.1437. Fly Zine Archive, The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books and gift of funds from Mary and Bob Mersky.

But it is the self-published, self-distributed nature of zines that is most indicative of the medium and their makers’ democratic ideology. It transgresses traditionally exclusive modes of publication—the zine is itself a form of protest. And contrary to magazines, blogs, and mainstream publications, zines are traditionally non-commercial, often even anti-commercial in their promotion of free art, knowledge, and use. The accessibility and affordability of zine production, distribution, and consumption is a direct extension of the countercultures in which the medium is so popular.

As Fly notes, “Zine content and quality has evolved with the accessibility and potential of digital modes of production.” As such, zines are an expression of DIY culture that balances the artist’s own touch with multiplicity, providing a personal connection between a zine maker and their readers. The result is a medium that is both socially and formally aware of modern changes to conceptions of art, authenticity, and originality.

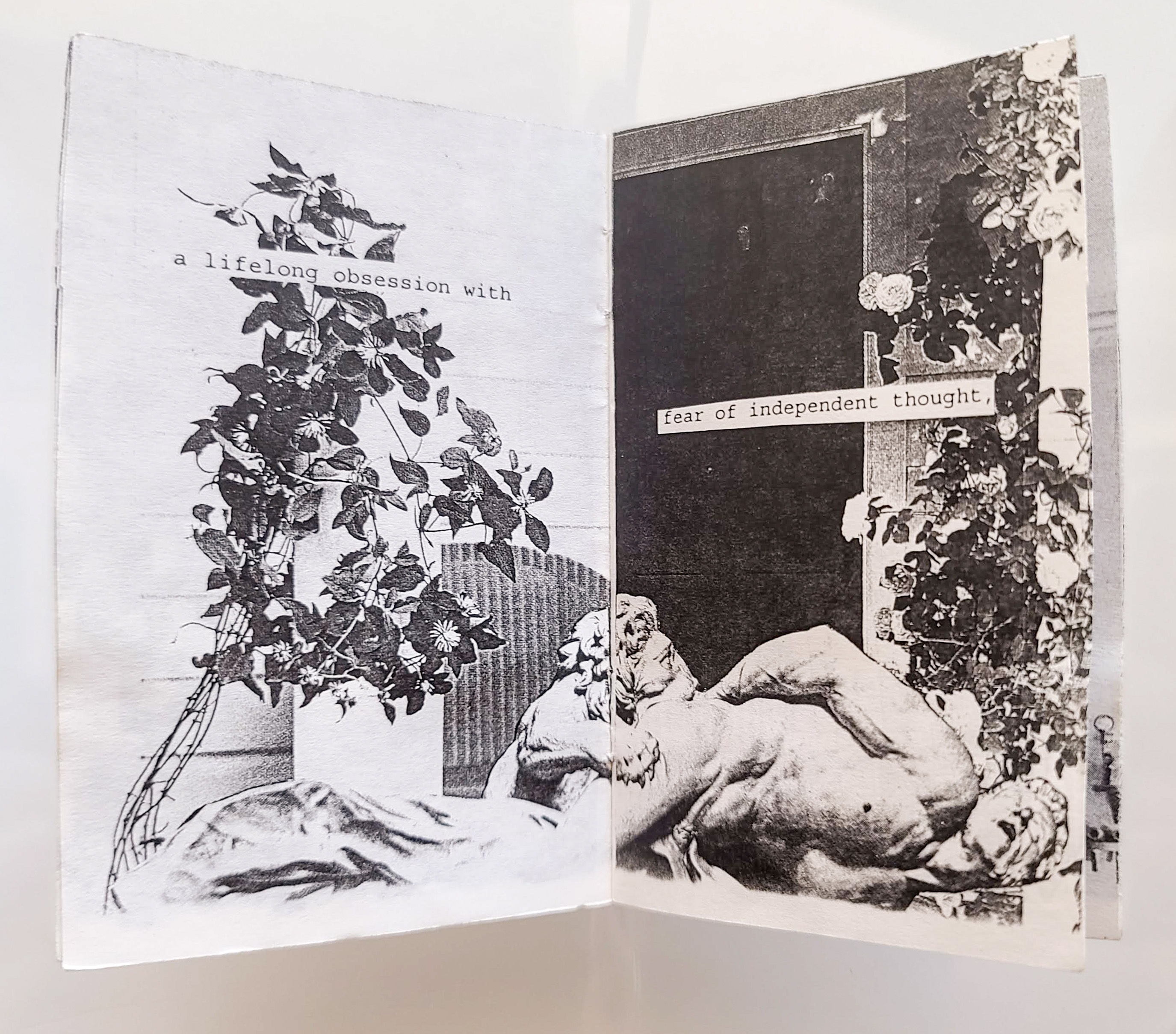

A highlight from the FZA is Kate Huh’s series Rebel Fux!, an anarcho-queer minizine (a smaller than usual zine) that cleverly collages found imagery and Huh’s own concise, self-reflexive poetry to confront gender, sexuality, heteronormativity, anarchism, and existence. Rebel Fux! minizines are printed on a single sheet of paper cut and folded into eight approximately 4 x 3 inch leaves without the need for binding—exemplifying how zine formats do not conform to mainstream print standards.

Minizines are also a favorite format of the San Francisco comics collective Mission Mini Comix. The FZA includes 59 of their minicomics, addressing themes of addiction, safe drug use, sexual health, and protest. Mission Mini comics are collaborative efforts, each leaf having been illustrated by a different member in their own respective style. The comics cohere nonetheless through the informative but satirical awareness of the text. Titles such as Happy Bunny gets V.D., Copy Wrong: The Sad State of Intellectual Property, Lil’ Dope Fiend Overdose Prevention Guide, and Separation of Corporation and State capture the group’s comedic approach to such serious topics.

The archive also has many issues of the tabloid zine Slug & Lettuce, started in 1987 by Christine Boarts Larson. The zine is a montage of text and image. Interviews with bands, music and zine reviews, and “Scene Reports” from punk shows around the world are juxtaposed with Larson’s fast-moving photography and contributing readers’ original comics and illustrations. Besides documenting global DIY and punk happenings, Slug & Lettuce also facilitated international communication and networking with its event and contact listings.

Above: Christine Boarts Larson, “Slug & Lettuce” #62, December 1999–February 2000, 2018.86.880. Below: Nick and Sarah, “Teenage Lobotomy: A Zine About the Institutionalization of Youth,” 2018.86.984. Fly Zine Archive, The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books and gift of funds from Mary and Bob Mersky.

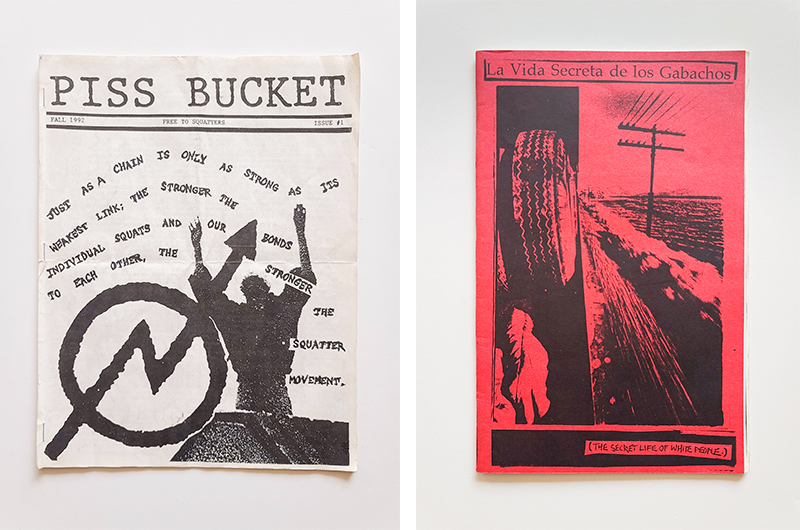

Squatting is one of the most prominent themes in the FZA. There are squatter zines and comics, DIY guides for squatters, histories of squatting, and even the squatters’ newsletter, Piss Bucket. The title of this zine is an allusion to the essential bathroom amenity of most squats, a joint-compound bucket. The insurgent, DIY essence of such squatter zines is representative of squatters’ larger ideas about voluntarism and self-autonomy. The zine contains detailed information about how to safely enter a vacant property, how to repurpose and fix its neglected parts, and how to care for it as a squat. It even provides a list of squatters’ rights and tactics to fight eviction. Beyond being art objects, zines like Piss Bucket are important historical documents for reconstructing the history of squatting in New York City and for understanding how Lower East Side squatter relations with city government—which had maintained the neglect of vacant property—evolved from hostility to partnership.

The archive also has several works by writer and activist Sascha Altman Dubrul, for a short time known as Sascha Scatter. La Vida Secreta de los Gabachos chronicles Sascha’s nomadic journey through the North American anarchist circuit as a teenager. He vividly records his experience hopping trains, squatting, and talking with strangers across America and Mexico. The legendary memoir is representative of a larger genre of vagrant travelogues, a rich vein in the archive.

Today, Sascha works towards reforming the practices, language, and culture that surrounds mental health care and institutionalization, another prominent theme of the archive. Teenage Lobotomy: A Zine About The Institutionalization of Youth confronts this directly. Teen artists and writers Nick and Sarah reflect on the mistreatment of youth patients in mental health and behavioral modification institutions while advocating for mental health care through art and creative expression. They also operated the Misled Youth Network, a series of zines featuring art, poetry, and musings on their experience as abused and misunderstood teens.

The FZA is massive in scale and cultural scope. But to Fly, the archive is more than just its count of art objects. “It preserves the continued evolution of rebel voice and artistic freedom,” Fly says, alluding to the archive’s most pervasive themes. Revolution, dissent, and irreverence, along with empowerment of individual and communal voice, tie all of the FZA’s contents together, making it a vital record of cultural evaluation and critique from many perspectives.

Left: Anonymous, Piss Bucket #1, 1992, 2018.86.737. Right: Sascha Altman Dubrul, La Vida Secreta de los Gabachos, 1996, 2018.86.1066. Fly Zine Archive, The Mary and Robyn Campbell Fund for Art Books and gift of funds from Mary and Bob Mersky.

The zines, comics, and other contents of the archive were intended to be read, seen, researched, and appreciated. As such, the FZA will be made publicly available in the Herschel V. Jones Print Study Room, as well as online via Mia’s collection database. The FZA will also enrich Mia’s exhibitions and public programming with its documentation of punk, squatter, anarchist, and DIY culture from the 1980s to the present. Moreover, the acquisition will further aid the continual effort to diversify Mia’s collection by gender, race, ethnicity, ideology, and medium. A zine archive is a unique addition to any museum’s collection, and Mia is proud that the Fly Zine Archive will make it one of the first.

Ian Karp is the John E. Andrus III Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Prints and Drawings.