By Diane Richard //

One-hundred thirty-three years ago, on a day in late November, Vincent van Gogh reached for his freshly painted canvas. It was during his self-imposed stay at a psychiatric hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, in the south of France, where his windows overlooked a grove of craggy olive trees with a mountainous backdrop.

That morning, near daybreak, was “bright and cold,” he wrote his brother Theo, but full of “very beautiful, clear sunshine.” He rendered that celestial orb in yellow hues—citron, mustard, egg yolk—daubed thick as frosting. (The sun occupies the same cosmos, one contends, as the moon depicted in The Starry Night, painted some five months earlier.) Mia’s Olive Trees (1889) would be the sole painting to contain a sun in his olive grove series—some of which will be on view this summer at Mia in “Van Gogh and The Olive Groves,” June 25 to September 18.

Having finished his en plein air session, his green eyes most likely shielded by the brim of a woven hat, Van Gogh gathered his tools: paints, palette, brushes, easel, and that canvas. Beneath the glare of that “big yellow sun,” as he later wrote to his sister Wil, he trudged back to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole hospital.

Along the way, he did what anyone who schleps what’s cumbersome might: he planted his finger in the still-wet oil paint.

That fingerprint would remain unobserved for 132 years.

•••

“Van Gogh and the Olive Groves” is derived from a larger exhibition of Van Gogh’s olive tree paintings, organized by the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, and the Dallas Museum of Art. Mia lent its Olive Trees painting to that exhibition, and, in turn, the other museums lent five paintings to Mia for this exhibition, an intimate opportunity to explore Van Gogh’s extraordinary art and practice.

While examining Mia’s Olive Trees, Dallas Museum of Art conservator Laura Eva Hartman discovered traces of a fingerprint near the top edge, just right of the sun. There’s no proof that the fingerprint smudge belongs to the artist, according to arts journalist and Van Gogh scholar Martin Bailey, but he is “virtually certain” it does.

We spoke with Bailey, who has written about Van Gogh for some 30 years, about the maker’s mark.

What did you think about the recent discovery of Van Gogh’s fingerprint?

Being a writer, I thought: That’s a nice story. It’s not entirely a surprise. Fingerprints turn up in his paintings occasionally, normally when seen under high magnification. What the viewer thinks immediately is, Is it the fingerprint of the artist? In most of the cases, it is.

How do you think it got there?

Van Gogh…was a little bit messy. He liked to be outside with his easel in the countryside with the view in front of him. He painted thickly with impasto paint. One would be more likely to get one’s fingerprints on thick paint; it would take longer to dry. He wasn’t one of those people who was obsessively wanting each color in the right place. He would do a landscape in a single day. He was less persnickety than someone who wanted a smooth finish.

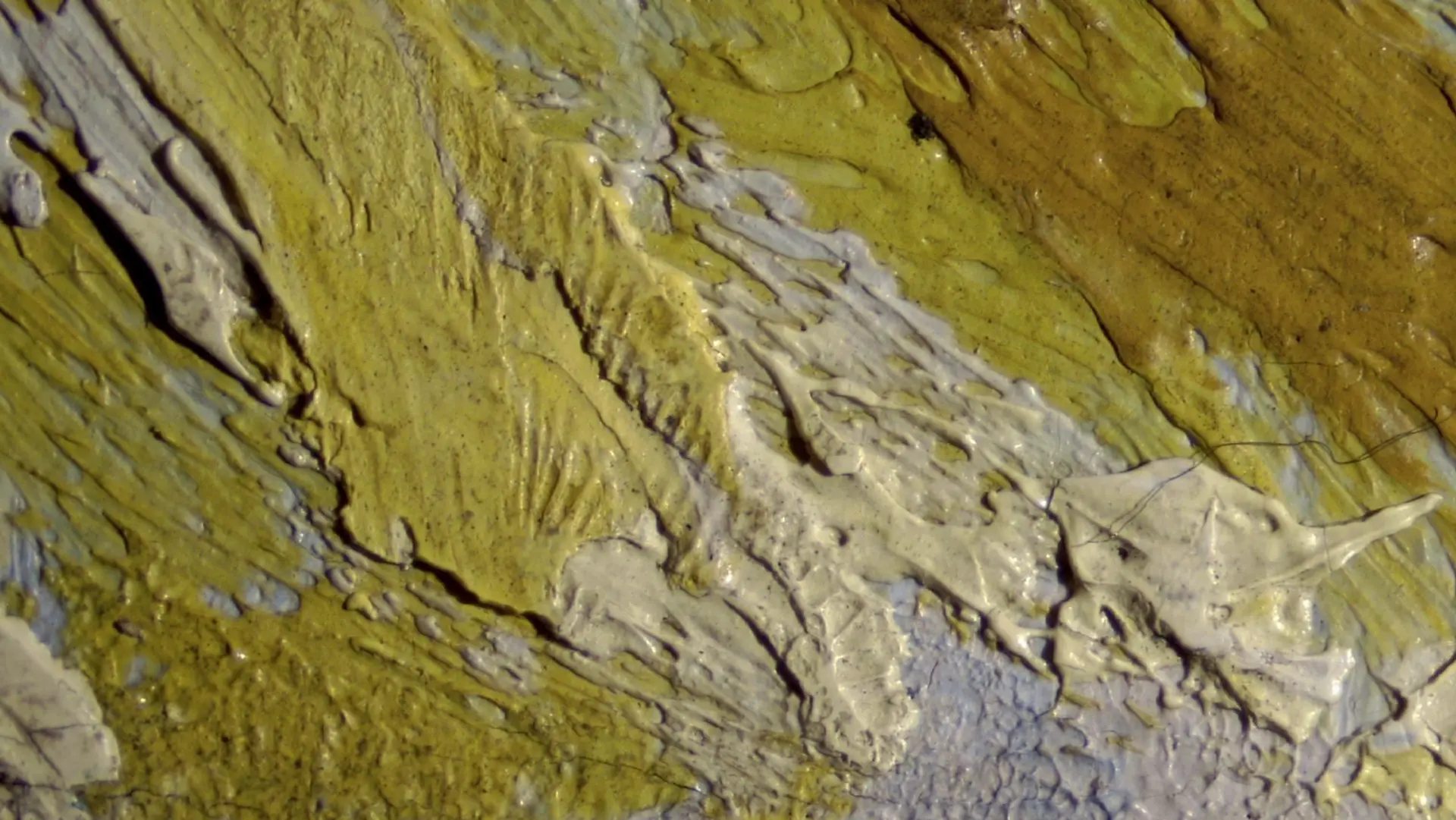

Photomicrograph of “Olive Trees,” showing the ridges of the newly discovered fingerprint. Photomicrograph taken at the Midwest Art Conservation Center, Minneapolis, by Laura Hartman of the Dallas Museum of Art

Does the fingerprint help viewers imagine the artist behind the artwork?

You might feel more engaged as a viewer. If you were very close, had excellent light, no protective glass, you might see it. But to see it you need complicated magnifying equipment. Modern scientific techniques, having become more sophisticated in the last 10 years, allow conservators to see what they couldn’t before.

A traditional emblem of the divine, the sun often appears in Van Gogh’s paintings as allusions to God and/or Christ. What else strikes you about the sun in Olive Trees?

The sun appears in quite a lot of Van Gogh paintings. He depicted the sun in a symbolic way. He wants to say, This is the symbolic sun and all the light is radiating out of it. You have circular brushstrokes around the sun. The other interesting thing is the shadows don’t work in the right way. The shadows from the olive trees go to the right. In reality they would go toward the viewer. Whether it’s a mistake, or if he’s done that as an exercise of artistic license, remains a puzzle.

At the asylum, Van Gogh painted The Starry Night in August and Olive Trees in November, 1889. Do you see any similarities?

He was interested in the sky. He was in the countryside, where there was very little artificial light. When he looked out at night, the stars would be very bright. The moon would be particularly strong. He was closer to nature than city dwellers would be today. The asylum was on the outskirts of a small town. Both pictures show his concern about the heavens, if you like.

Also, notice the mountains: they are the same mountains. They’re depicted from a slightly different position, about a half kilometer away. It’s a slightly wider view in The Starry Night.

Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” (left), collection of the Museum of Modern Art. “Olive Trees” (right), collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

What can viewers learn by seeing these olive grove works together?

It will increase visitors’ interest in Van Gogh, seeing a range of work of different media and different times. It’s a healthy answer to the Van Gogh immersive experiences. I haven’t anything against them. If it gets you interested, that’s fine. But it’s not the same as seeing the real thing.

What sustains your interest in Van Gogh?

Over 30 years ago, someone told me that Van Gogh lived in London. I’m a Londoner, so I got interested in where he lived, in Brixton. I started doing research on that. He’s a fascinating artist to work on. Viewers are just as interested as Van Gogh the man as Van Gogh the artist. We are very fortunate to have the 900 letters that are surviving. It’s almost a diary. He’d say: “I’m working on this, the olive groves, the sun beating down on me.” I never get bored. There is always more to discover.

Martin Bailey is the author of the new book Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame.He writes the weekly Adventures with Van Gogh blog for The Art Newspaper.