When I was 23 years old, fresh out of journalism school, I went to work at The Associated Press bureau in Minneapolis. This was in 1995, just before the internet and email became widely accessible, and the AP still distributed the news — all the news that was fit to print — by printer.

In a hall just off the newsroom, a row of teletype machines printed the venerable wire service’s stories from various bureaus across the country — all day, every day. A great roar of information, spooling into heaps of paper on the floor like mushroom clouds. When particularly important news went out, the printer would ding: five bells for a “bulletin” (maybe once or twice a day), 10 or more for a “flash” (maybe once a year).

This scene was replicated in every respectable newsroom across the world, at newspapers and television stations and radio stations, where someone manned the teletype room and ripped off the most important stories as the news rolled in. Looking at original wire copy of President John Kennedy’s assassination, now archived at the AP, you can see stray letters printed across the paper — an “A” here, a “Y” there — suggesting someone had excitedly ripped the story off the printer even as it was printing.

Original AP wire copy describing the assasination of President Kennedy. The floating letters suggest the story was ripped from the printer even as the machine was continuing to print.

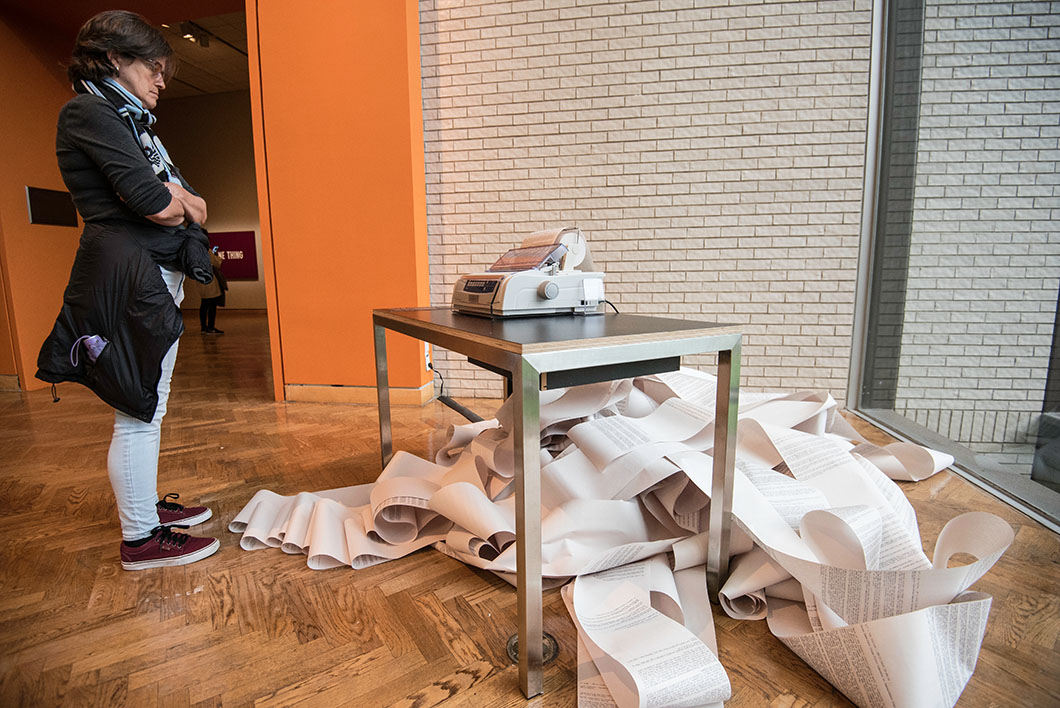

Right now, one of the few places you can still see this happen is at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, where a news printer has been parked at the entrance to “Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975,” an exhibition of anti-war art organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. The machine is an art installation, conceived by Hans Haacke in the late 1960s as a commentary on the vast amount of information — and disinformation — being generated by the war. News shifted public opinion, and as it gathered beneath the printer so did it accumulate in the public consciousness, almost too much to digest.

If Vietnam was the first televised war, it was also the first war of the information age. There was plenty of reporting; the question was what to believe. However, it generally wasn’t the reporting that was questioned then, it was the sources.

Anyone of a certain age remembers seeing CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite or an anchor on another station being handed a scrap of wire copy, hot off the printer, and saying “This just in.” (In fact, that was the title of Cronkite’s biography.) There were only so many news outlets and most people paid attention to them. In 1975, at the close of the war, 90 percent of Americans surveyed could identify Cronkite and 90 percent respected him. He was, as one poll concluded, “the most trusted man in America.”

By contrast, when Dan Rather retired in 2005, only 21 percent of people polled said they believed him all or even most of the time. In the 14 years since, the attention and trust of the American public has only further splintered.

Haacke had not intended his teletype machine to be an artifact — it was modern technology when he first installed it, in 1969. And it embodied, if anything, unquestioned authority. After one of Cronkite’s Vietnam specials, in 1968, in which he declared the war “mired in stalemate,” President Lyndon Johnson was said to have muttered, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost the war.” The anecdote is almost certainly apocryphal (shortly after the program, an unshaken Johnson — speaking in Minnesota — urged a “total national effort to win the war”) but it encapsulates the persuasive power of the media at the time.

A visitor observes Hans Haacke’s “News” installation at the entrance to “Artists Respond,” an exhibition of Vietnam-era art in Minneapolis.

Today the teletype serves as a commentary on our time, too, an anachronism in a more cynical era. Indeed, it was the war — and Watergate, at the same time — that cracked open the cultural divides now threatening to engulf us. If we can no longer conceive of getting all our news from one source, we can also hardly conceive of trusting the sources of those who think differently. We have more choices but less faith.

As Haacke’s machine, simply called News, chatters away at the museum, it is both a source of irritation to some of the staffers collecting tickets and a legitimate source of news — it’s connected to multiple news services, from the New York Times to FOX News to The Guardian. Visitors are encouraged to wade into the billowing paper and discover the latest stories as they roll in. To read even a few of them—from Ukraine-related arrests to a profile of a harpist to a piece exhorting the benefits of cheddar cheese — is to realize that life has always gone on no matter what “the news” has to say about it. And on and on and on.

Top image: News service copy accumulates behind Hans Haacke’s “News” installation at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.