5 Prints That Show How Weird the Renaissance Was

By Tim Gihring

July 11, 2025—The Renaissance, which began in Italy some 700 hundred years ago, was idealized even as it was happening, as a kind of beacon of beauty and reason that would lead the way out of the Dark Ages.

“It is but in our own day that men boast that they see the dawn of better things,” the Florentine philosopher Matteo Palmieri noted, not a little boastfully.

But the Renaissance was also just plain weird. As Tom Rassieur, Mia’s John E. Andrus III Curator of Prints and Drawings, demonstrates in his new exhibition “The Weirdening of the Renaissance,” artists reveling in newfound freedoms soon began to drift toward the edge of the imagination. They conjured bizarre scenarios and curious creatures, evoked witchcraft and bawdy humor, in ways that can still puzzle and shock.

Here, in five prints from the show, Rassieur invites you to imagine a Renaissance that aimed both low and high, an era as strange as it was beautiful.

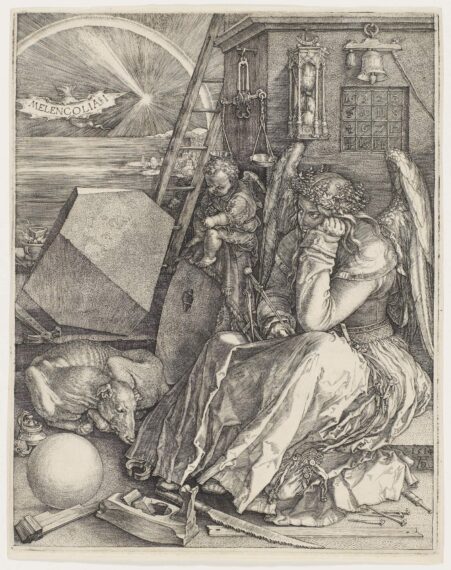

Melencolia I, by Albrecht Dürer, 1514

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528), Melencolia I, 1514, engraving. The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund, Proceeds from the 2011 Minneapolis Print and Drawing Fair, the Richard Lewis Hillstrom Fund, Gift of Funds from Nivin MacMillan, the Winton Jones Endowment Fund for Prints and Drawings, and Gift of Herschel V. Jones, Gift of Mrs. Ridgely Hunt, and Gift of Miss Eileen Bigelow and Mrs. O.H. Ingram in Memory of Their Mother, Mrs. Alice F. Bigelow, By Exchange, 2012.16

Albrecht Dürer, the master printmaker from Germany, pulled this image of a melancholic craftsman seemingly out of nowhere. It’s packed with creative flourishes: a rainbow at night, a geometric form invented by Dürer, a so-called magic square (any way you add up the numbers, they always total 34).

And yet the angelic figure, for all his powers, is crestfallen. The block is chipped and weathered. The tools are broken and abandoned.

“It’s a statement about the limitations of the physical world versus the ideal world in the artist’s imagination,” Rassieur says.

“It’s the artist’s dilemma, and Dürer has made a very weird image to express this idea of creative ambition and frustration.”

The print became extremely influential among artists, its strangeness a kind of permission slip to “release themselves from the shackles of the past,” as Rassieur puts it, “and make whatever the heck they want.”

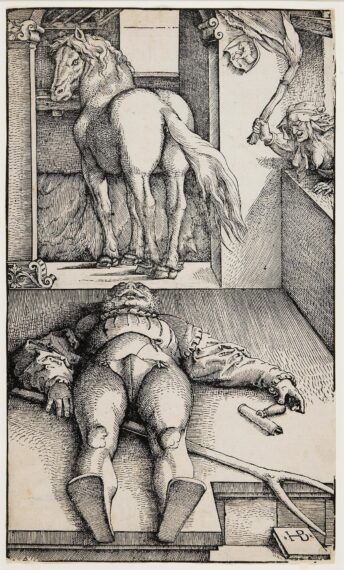

Bewitched Groom by Hans Baldung, c. 1544

Hans Baldung (Grien) (German, 1484–1545), Bewitched Groom, c. 1544, woodcut. Gift of Herschel V. Jones, 1926, P.10, 618

Hans Baldung studied under Dürer, and from then on would always try to one-up him (and other artists) with some inventive twist.

Here, a stable hand has been knocked out cold. Was it the horse? The witch fleeing through a window? You almost feel like you’re tumbling into the scene, an unwitting witness to a curious crime.

Indeed, it’s a riff on a famous Renaissance painting by Andrea Mantegna of the dead Christ, his body stretched out on a stone, his feet in the foreground.

“Baldung is borrowing that and twisting it, using it for this image not of sacred sorrow but of witchy wonder,” Rassieur says. “It just begs for two people to look at it together and speculate on what happened.”

Parnassus Profaned by the Master HFE, 1530–1540

Master HFE (Italian or German, active Italy 1525–1540), Parnassus Profaned, 1530–40, engraving. The Winton Jones Endowment Fund for Prints and Drawings, Proceeds from the Minneapolis Print and Drawing Fair, and Gift of Funds from the Winton Jones Foundation, 2019.109

This engraving, by an artist known only by the initials HFE, shows Greece’s Mount Parnassus. Here, the gods were said to practice poetry, music, and other high-minded pursuits, a scene famously depicted by Renaissance icon Raphael in a reverent, formal fresco in the Vatican.

HFE had other ideas.

“There are people having sex, animals having sex, even the trees in the background are having sex,” says Rassieur.

The winged horse Pegasus, the embodiment of classical ideals, is hightailing it out of there. “Instead of appealing to our higher and nobler senses, it’s an image meant to appeal to real people and how they really feel.”

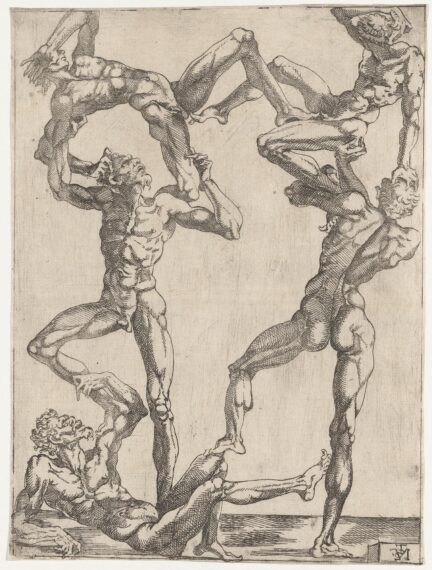

Pyramid of Five Men, Attributed to Juste de Juste, c. 1540–1550

Attributed to Juste de Juste, Pyramid of Five Men, c. 1540–50, etching, The Barbara S. Longfellow Endowed Acquisition Fund. 2024.79

No one knows for sure who made this print, much less why. Possibly it was the Italian artist known as Juste de Juste, one of many artists who fled Rome for the forest of Fontainebleau, in France, and worked for the French king.

“They had a very rich patron,” Rassieur notes. “They had the freedom to do what they wanted to do.”

What this artist wanted to do, apparently, was surprise. “There was just nothing like this image before,” Rassieur says, “and there’s been little like it since.”

The five naked men are so lean, they appear not only naked but flayed, their muscles displayed like sacks of walnuts. Two men seem to be tickling each other with their toes.

The print is extremely rare, Rassieur notes, possibly for good reason. “It may have been a bit of forbidden fruit.”

Allegory of Life, by Giorgio Ghisi, 1561

Giorgio Ghisi (Italian, 1520–1582), Allegory of Life, 1561, engraving. Bequest of Herschel V. Jones, P.68.167

A goddess, an old man, a leopard, a shipwreck, a lightning bolt from heaven. It’s anyone’s guess what is happening here, though it appears to be an allusion to the River Styx, which, according to Greek myth, separates the living from the dead.

“It’s all just perplexing,” Rassieur says, though the print was very popular in its day. Perhaps people used it to show off their classical knowledge, connecting the symbolism to ancient myths.

“You can stare at this image, and it sets your mind free because it sparks ideas. You wonder, ‘What is life about, how am I going to live my life?’ It’s an image that is forever strange to you—you never figure it out.”

More About the Exhibition

“The Weirdening of the Renaissance” features nearly 30 prints from Mia’s collection, exploring the range of Renaissance strangeness, on view in Gallery 344 through November 30, 2025.