How Angkor Became a “Lost City”

By Tim Gihring

December 15, 2025—In the spring of 1858, Henri Mouhot set sail from London with his King Charles spaniel, Tine Tine. He was bound for Southeast Asia, a five-month journey full of “annoyances in plenty,” as he wrote in his journal. When he landed in Singapore, he may have wondered if it was worth the trouble.

A self-styled naturalist from the French-Swiss border region, Mouhot had never traveled farther south than northern Italy. But he had wrangled a commission from several scientific societies to explore Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand (then known as Indochina or Siam), a region the French were keen to rule. Two days before Mouhot’s arrival in September, France invaded Vietnam.

Mouhot quickly moved from Singapore to Thailand. “Bangkok,” he wrote, “is the Venice of the East. Whether bent on business or pleasure you must go by water . . . lying luxuriously at the bottom of your canoe.”

By December he was in Cambodia, which seemed to him to be a kind of lesser Thailand until he traveled out to the plains, in the center of the country, and was taken by his guides to Angkor.

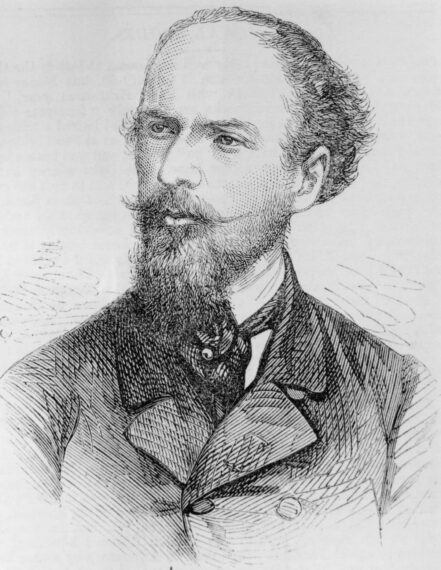

A portrait of Henri Mouhot by an unknown artist. Mouhot spent just three weeks exploring and sketching Angkor Wat, but was credited with its “rediscovery” back home in France.

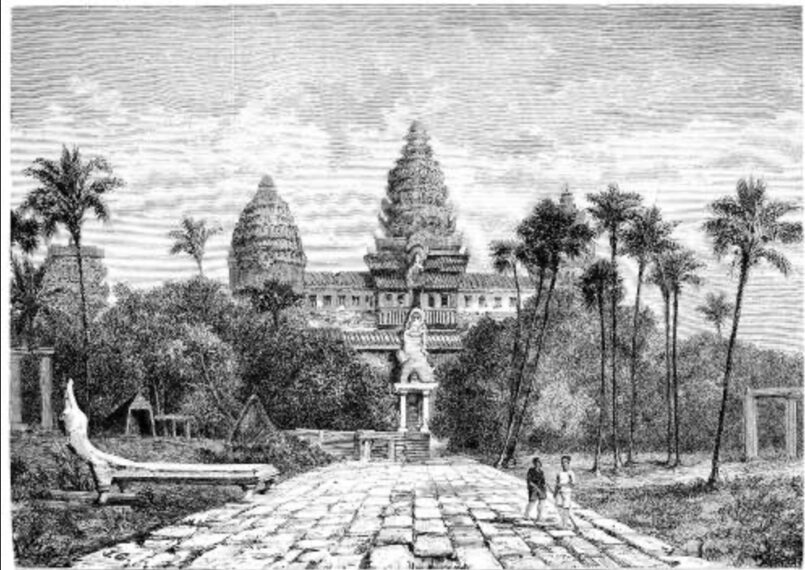

Then, as now, the vast temple complex just outside the city of Angkor, known as Angkor Wat, was filled with pagoda-like spires, artificial lakes, and enormous stone faces overgrown by jungle. It seemed a portal to another time, when the Khmer Empire ruled the region with Angkor as its capital. A marvel of engineering, art, and faith. The evocative source of the Hindu and Buddhist statuary now assembled at Mia in the special exhibition “Royal Bronzes: Cambodian Art of the Divine.”

Mouhot was overwhelmed. “One of these temples,” he wrote, “a rival to that of Solomon and erected by some ancient Michael Angelo, might take an honorable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome.”

Mouhot spent three weeks exploring and sketching Angkor Wat. When his journal was published in 1864, it captivated his fellow Europeans. They had seen very few images of Southeast Asia. Mouhot’s account was filled with them. The engravings of vine-encrusted temples, wildlife walking among them, made Angkor appear like a lost paradise, abandoned by its creators. Mouhot was hailed as its rediscoverer.

Proposed 3D re-creation of the head and bust of the West Mebon Vishnu, based upon the results of the stylistic and technological study.

First Encounters with Angkor

In fact, Mouhot was just the latest in a long line of foreigners to come across Angkor. The first arrived while the complex was still being built: Zhou Daguan, an emissary of the Chinese emperor, who sailed up the coast of Vietnam in 1296 before turning inland.

He came, apparently, to collect a tribute for the emperor but found a great ruler already there: the Khmer king. By the late 1200s, the Khmer Empire had been around for some 500 years and was at the height of its power, encompassing Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, and much of Vietnam.

Daguan was impressed. Angkor in the 1200s was likely the largest city in the world, sprawling hundreds of miles across the plain. Nearly a million people may have lived there at a time when only about 350 million people lived on the entire planet.

He was especially fond of the bronze statues that seemed to be everywhere in the city and the temples outside it. In a lake, he saw what he thought was an enormous reclining bronze Buddha. In fact, the statue depicts Vishnu, the Hindu god who protects the universe—likely the very same reclining Vishnu that is now the central attraction of “Royal Bronzes.”

A Bustling Place of Pilgrimage

After Daguan returned to China, the Khmer kingdom carried on for another 150 years. It built bigger and better temples and kept its enemies at bay, even as its strength weakened, until finally Angkor was taken by the Ayutthaya kingdom to the north. The conquering king reportedly took 60,000 families back with him to Thailand—along with hundreds of gold, silver, and bronze statues.

The Khmer king retreated to southern Cambodia. The court wandered for hundreds of years, setting up new capitals here and there as the empire shrank. Then in the 1500s, while the king was out hunting elephants in the center of the country, he came across a grand city overgrown by jungle.

The king himself had rediscovered Angkor. He reinstalled his court among the ruins and—centuries before Mouhot—European adventurers and missionaries began to come across it. “An exceptional phenomenon,” one visitor described Angkor, “which may be regarded as one of the Wonders of the World.”

By the 1600s, Angkor Wat was full of Buddhist pilgrims from all over—Cambodia, Thailand, Japan. “The temple is renowned among five or six kingdoms,” a missionary from France acknowledged in 1668, “as Rome is among the Christians.”

An engraving of the main temple at Angkor Wat, made after a sketch by Henri Mouhot and included in the 1864 publication of his journal.

The Push for Preservation

In the 1800s, as France’s colonial ambitions turned to Southeast Asia, the tone of French explorers in the region began to shift. Angkor, they insisted, was all but abandoned, a marvel in need of saving.

In 1863, a few months before Mouhot’s journal came out, a French expedition made its way to the king of Cambodia at the country’s new capital of Phnom Penh. It is no longer possible “to deny,” claimed the French admiral leading the expedition, “that the pitiful Cambodia of today once nurtured and can still nurture a great nation—a nation both artistic and industrious.”

The king signed over his country, which became a French protectorate. When Mouhot’s report came out, the following year, Angkor became a symbol of the French colonial project. Artifacts from the area began to flow to France, traded with the king of Cambodia for paintings, engravings, and statues from Paris.

Mouhot knew nothing of this—neither the rush for Angkorian art nor even his reputation as the rediscoverer of a lost city. He had no way of knowing the intense interest his journal would inspire among archaeologists and other historians, work that is still ongoing. Indeed, two such researchers—David Bourgarit, an archaeometallurgist at the Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, and Brice Vincent, an archaeologist and professor at the École Française d’Extrême-Orient, are the co-curators of “Royal Bronzes.”

Mouhot had died in Laos shortly after leaving Cambodia, likely of malaria, and was buried outside the village where he and Tine Tine had settled. His journal was published posthumously, some six years later.

In his writings, Mouhot seems more interested in bugs than geopolitics. Between the engravings that so entranced his readers, and the fanciful descriptions of people and places he came across, are copious entries on insects and other animals—notes from a naturalist who hoped to leave a legacy in science. One beetle in particular deeply impressed him. Large and black, it is now named in his honor: Mouhotia gloriosa.

See More at Mia

“Royal Bronzes: Cambodia Art of the Divine” is on view in the Target Galleries through January 18, 2026.

You can see more contemporary expressions of Cambodian culture in “Sopheap Pich: In the Presence Of,” on view in the Sit Investment Associates Gallery (G200) through February 1, 2026.