“Gatsby at 100” Shows Why the Jazz Age Still Jumps

By Tim Gihring

October 10—The Great Gatsby was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s worst-selling novel during his lifetime. Mind you, his life wasn’t especially long—he died in 1940, at 44, of a heart attack brought on by years of alcohol abuse. Had he lived just a little longer, into the World War II era, he would’ve seen a huge shift in his and the book’s fortunes, owing largely to the novel’s inclusion among the reading materials sent overseas with American soldiers. Many enjoyed Fitzgerald’s dark, quirky story of a wealthy midwesterner who can’t buy love, and it has never left the popular imagination.

It’s not his best writing. Check out The St. Paul Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald for better prose and local color. “Winter Dreams,” set in the Minnesota resort town of Black Bear Lake, amounts to a first draft of the Gatsby tale.

But The Great Gatsby is by far his most popular book—especially among people who’ve never read it. Film and stage adaptations have been coming out since the year after its publication. Now the story is something like a meme, shorthand for that short-lived era between the wars when people actually seemed to enjoy themselves.

This year is the book’s 100th anniversary, and it’s being celebrated especially hard in the Twin Cities, where Fitzgerald grew up. “Gatsby at 100,” now on view at Mia, adds to the party with rarely seen paintings, books, and works on paper by artists like Henri Matisse, Oskar Kokoschka, and others inspired by the Jazz Age—a term coined by Fitzgerald himself.

Here, a few highlights of the show that go a long way toward explaining the enduring popularity of both the book and the era.

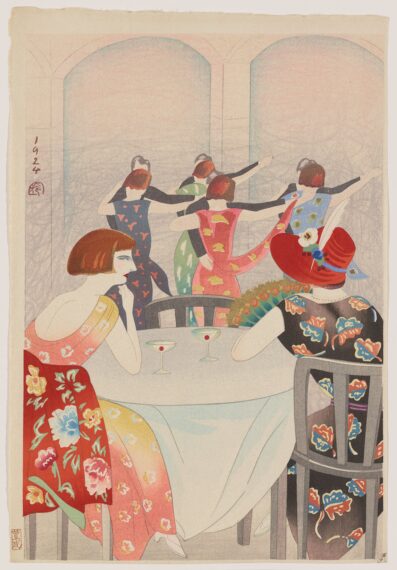

Yamamura Kōka (Toyonari) (Japanese, 1886–1942); Publisher: Yamamura Kōka Hanga Kankōkai, Dancing at the New Carlton Café in Shanghai, 1924, woodblock print, ink and color on paper with mica. Gift of Funds from Ellen Wells, 2014.35

The Jazz Age got around, and for good reason. It was the era of “anything goes,” and it looked great doing it. This Japanese print from 1924 captures the era’s global influence, from the bobbed hair to the sleek architecture of this Shanghai nightspot. That this modern scene was created in the traditional form of a woodblock print adds some aesthetic intrigue—a juxtaposition but also fitting, since woodblock prints were the medium of the moment in 19th-century Japan, capturing contemporary entertainment that, like jazz in the 1920s, seemed irredeemably decadent.

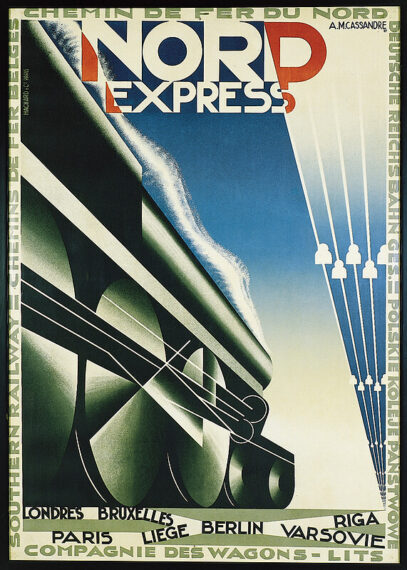

Adolphe Mouron Cassandre (French [born Ukraine], 1901–1968); Designer: A. M. Cassandre; Printer: Hatchard et Cie, Nord Express, 1927, color lithograph. The Modernism Collection, Gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota, P.98.33.9

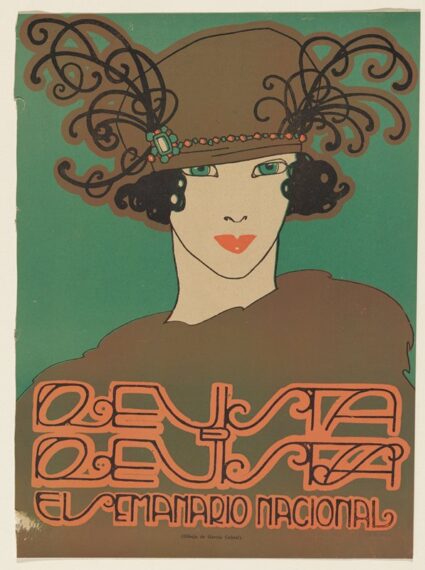

Ernesto García Cabral (Mexican, 1890–1968), Head of a Woman, 1924, color lithograph. The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund, 1964

The Great Gatsby can be read as a kind of diss novel. Fitzgerald got his heart handed to him in college by a Chicago debutante whose family thought his money wasn’t old enough or plentiful enough. His bitterness over such class distinctions would show up in almost everything he wrote, especially his female characters. Still, the emerging independence of women is a major theme of Gatsby, and the novel’s many visual adaptations have created a template of breezy beauty. Stylish, self-assured, up for anything—the one who got away.

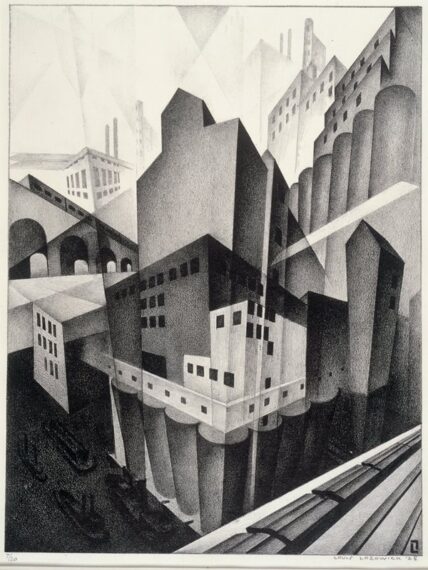

Louis Lozowick (American [born Russia], 1892–1973); Printer: George C. Miller, Minneapolis, 1925, lithograph. The John R. Van Derlip Fund, P.74.5