When Trees Could Talk: The Curious History Behind Mia’s “Timber!” Exhibition

By Tim Gihring

August 27, 2025—Egon Schiele’s 1913 painting of a sawmill, surrounded by clear-cut forest, has always been something of a mystery. The Austrian painter felt an unusual kinship with nature, even by the standards of late-Romantic artists.

He once wrote that “every tree has its face,” that he could perceive “its kind of eyes, its kind of arms, its components, its organism.” And yet, here is this scene of deforestation, a whole community of organisms ripped apart by the blade gleaming inside the sawmill. What was Schiele trying to say?

“Timber! Art and Woodwork at the Fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire” offers some possible answers. The exhibition, opening August 30, 2025, at Mia, is designed around the sawmill painting, on loan from a private collection. The other works suggest two outcomes of the sawmill’s work: a wooden bridge, depicted in another Schiele painting, and wooden furniture mostly created by the influential Austrian designer Josef Hoffmann.

Max Bryant, Mia’s James Ford Bell Associate Curator of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture, organized the show. Here, he explains the various historical threads he wove around this enigmatic image.

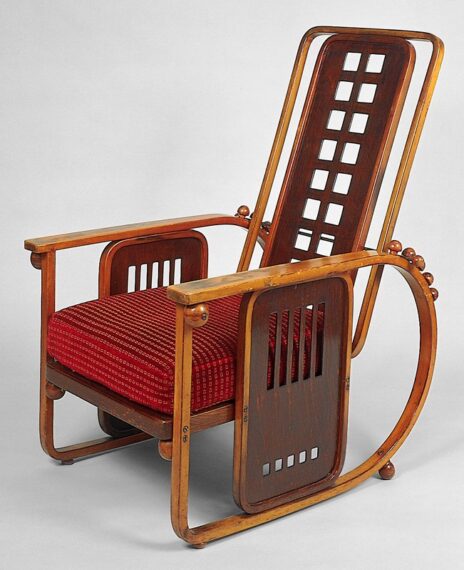

Josef Hoffmann (Austrian, born Moravia [Czech Republic], 1870–1956), Sitzmaschine reclining armchair, model no. 670, c. 1905, stained and laminated beechwood, brass, original cushions. The Modernism Collection, Gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota, 98.276.243

It is a real place that Schiele visited, in Carinthia, a forested area of Austria. But he has really exaggerated the contrast between the sawmill, which he shows as falling apart, and all this freshly cut timber around it. The mill is barely holding itself together, yet it is also in the process of deforesting this landscape.

You’ve described this painting as a powerful comment on the Anthropocene. What do you mean by that?

The Anthropocene is this term that has emerged in the last 20 years or so to describe the idea that this epoch of Earth’s history is one characterized by human intervention. That seems to be a very important context for this painting, which depicts a human intervention on the landscape in a way that feels unnatural. And that’s because Schiele has stripped away so much of what we expect from a landscape painting: there’s no sense of perspective, no sense of scale or space.

We’re left with symbolism, really, a commentary.

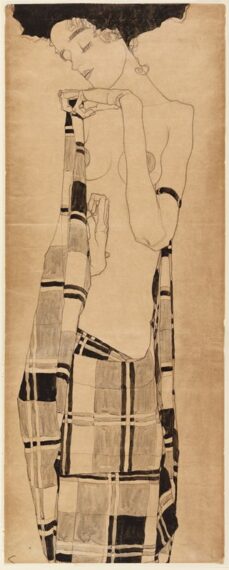

Yes, it seems he is commenting on the human impact on nature. And we know from his letters that he sees himself as being inspired, in this very Romantic way, by a pantheistic view of nature and the artist as especially in tune with nature.

For instance, he loves these forest shrines that were a feature around Vienna, honoring the saints among the trees. He writes this wonderful comment about trees in a letter to Josef Hoffmann, essentially that “I can speak with all living creatures, even with plants and stones.”

What is Josef Hoffmann’s connection to Schiele?

Hoffmann is a very talented architect and designer in Vienna who, around 1900, becomes fascinated by a kind of restrained, rectilinear mode. And part of that is adopting the new technology of bending wood—he can now create these forms that are very refined and simple with just a couple of pieces of wood bent together. In his designs, wood takes on forms that had never been attempted before.

Egon Schiele (Austrian, 1890–1918), Standing Girl, c. 1910, conté crayon and tempera wash over black chalk on brown wrapping paper. The John R. Van Derlip Fund and Gift from Dr. Otto Kallir, 69.7

Hoffmann is running a business—the Wiener Werkstätte, which is producing everything from furniture to silver to textiles. He doesn’t have the space to be expressing great poetic visions in the same way as Schiele. But I think that’s part of why he develops a relationship with him. He stocks Schiele’s paintings, and he commissions Schiele to make decorative elements for the buildings he’s designing.

Some of this bentwood furniture ends up in the cafés that are such a big part of urban life then. Do these chairs reflect something about café culture itself?

They embody a flexibility, like you’re ready for the next new thing. They are not classical—they are unburdened by any historical associations that chair design might have previously manifested. They’re really an expression of what was happening in the 1900s, this feeling that you were participating in something modern.

At the same time, the Austro-Hungarian Empire is slowly decaying.

The empire is made up of all these separate regions, and part of the tension at this time is their desire for autonomy, even as the empire is trying to expand. So there’s this disconnect between the center of the empire, in Vienna, and the periphery.

You can see this in the exhibition. The sawmill is on the periphery, near the border with Italy now. Whereas the bridge in Schiele’s painting is right between Vienna and Budapest, the two great urban centers of the empire. In 1913, many people believed the empire would go on forever. But really, there was nothing holding it up—it’s like the sawmill that is churning out timber but is itself falling apart.

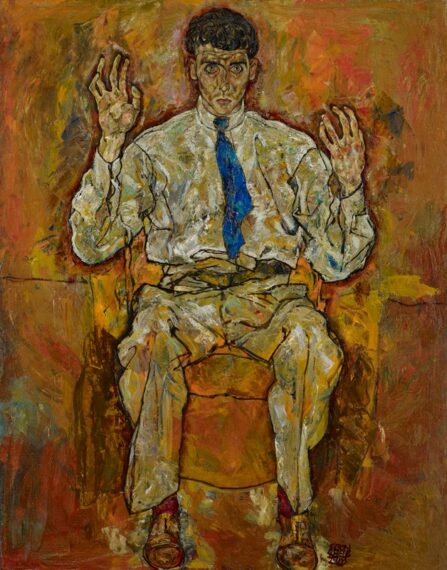

Egon Schiele (Austrian, 1890–1918), Portrait of Albert Paris von Gütersloh, 1918, oil on canvas. Gift of the P.D. McMillan Land Company, 54.30

What becomes of Hoffmann and Schiele and their visions?

The story ends for Egon Schiele just a few years later—he’s 28 when he dies of the Great Influenza epidemic. Hoffmann lives on, but he’s not at the center of what’s modern anymore. After the war, the funds weren’t there to build these beautiful villas and houses that had been the heart of his work.

Modernism itself changes after the war, and you can see that in the exhibition in Schiele’s great masterpiece at Mia, the portrait of Albert Paris von Gütersloh. Gütersloh writes a book after the war, a retelling of the story of Cain and Abel that is really about a loss of innocence, which I think a lot of people felt after the war.

Abel seems to be based on Schiele, and he’s killed by Cain when he reveals that man has been exiled from paradise. It really links what Schiele was doing before the war—exploring these connections between man and nature—to the larger sense of exile that came after.

More About the Exhibition

“Timber! Art and Woodwork at the Fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire” is on view at Mia in the Cargill Gallery from August 30, 2025, to January 4, 2026. Join the opening celebration on August 30 at 11 a.m.