Getting the Shot: How Photographs Have Shaped Our Understanding of Historic Sites

By Laura Silver

February 17, 2026—When British photographer Francis Frith traveled to Egypt in the mid-1850s, he brought along bulky cameras, chemicals, glass plates, tents, a portable darkroom, and a small staff to assist. He made hundreds of images of the ancient monuments, often in conditions of extreme heat, wind, and sand. The photos were widely circulated in Britain, where they shaped Victorian understanding of Egypt as a land of wonder and antiquity.

Expedition photographers like Frith, as they struggled with their heavy equipment and inhospitable environments, were inventing photographic conventions that would satisfy their employers and consumers back home. Today, our cameras are in our pockets and the world is at our doorstep, but those same 19th-century conventions still guide us to that one, can’t-miss, iconic shot.

How Photography Trained the Eye

In fact, the landmarks themselves know what we want to see. Disney World has its “photo spots,” stops along U.S. Route 66 have “selfie points,” and the Matterhorn—the famously photogenic peak in the Swiss Alps—has a red metal frame. Photography, it could be said, has shaped how we experience landmarks rather than the other way around.

The Matterhorn helpfully frames itself.

The exhibition “Site Lines: Photographing Historic Spaces,” on view through April 12, 2026, in Mia’s Perlman Gallery (G368), reveals some of the photographic conventions that have become standard practice since Frith’s day. Drawn entirely from Mia’s collection, the artworks explore photography’s role in determining how we experience and depict famous views.

“We’ve been trained by art in how to consume a view, although we’re not necessarily conscious of it,” says Leslie Ureña, who is Mia’s Associate Curator of Global Contemporary Art and organized the show.

“I believe we have an internal visual data bank. We want the horizon line. We want something in front to show distance. We put people in the picture to give it a sense of the scale.”

Before the Camera: Painting as a Visual Template

But if our “visual data bank” is filled with nearly 200 years of landscape photographs, what did 19th-century photographers like Frith have as a reference? The answer partly lies in Mia’s Gallery 344, where works by Scottish painter David Roberts depict his impressions of Africa and the Middle East.

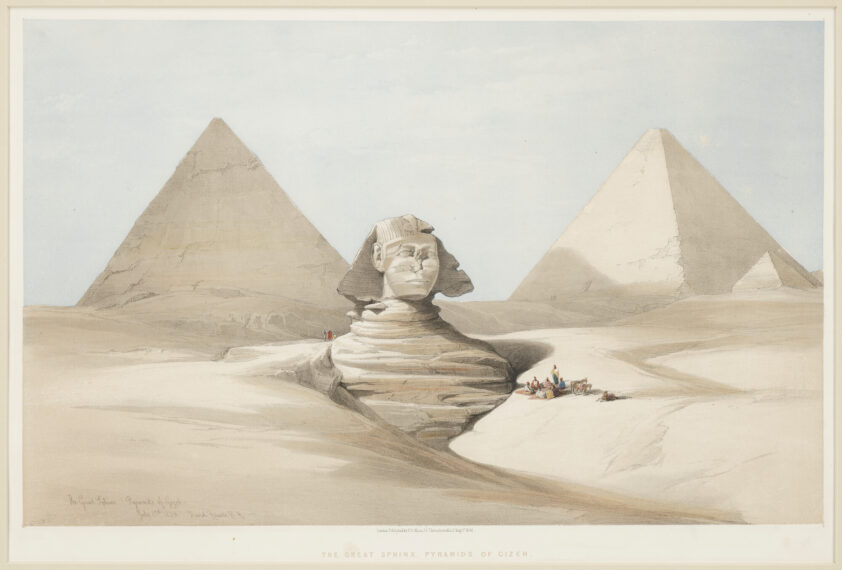

David Roberts (British, 1796–1864), The Great Sphinx, Pyramids of Gizeh, 1846, tinted and hand-colored lithograph; Louis Haghe, lithographer; Sir Francis Graham Moon, publisher. Bequest of Frances H. Graham, 2024.74.38

Just 20 years before Frith’s expedition, Roberts journeyed through Egypt, capturing its monumental temples, tombs, palaces, and landscapes in watercolors. His on-site drawings were later transformed into hand-colored lithographs and published to great success, providing Victorian Britain with its first look at many famous historical and biblical sites.

But where 19th-century photographers like Frith aimed for clarity, scale, and factual precision—an objective, almost scientific record of ancient civilizations—Roberts aimed to convey romance and mystery. Ironically, many of their works capture the same views.

“Early photographers such as Frith would have been familiar with what David Roberts was doing,” says Ureña, “to the point that he himself would have had Roberts’s images in his own visual data bank when he embarked on his own project.”

Contemporary Photographers, Timeless Conventions

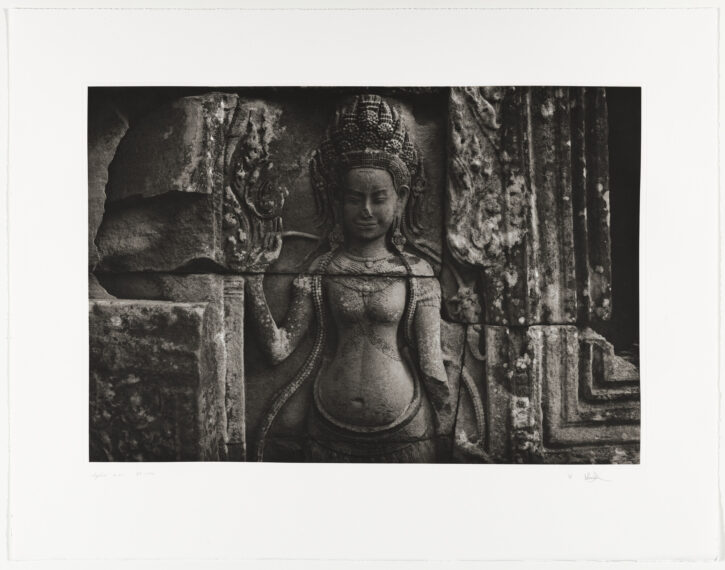

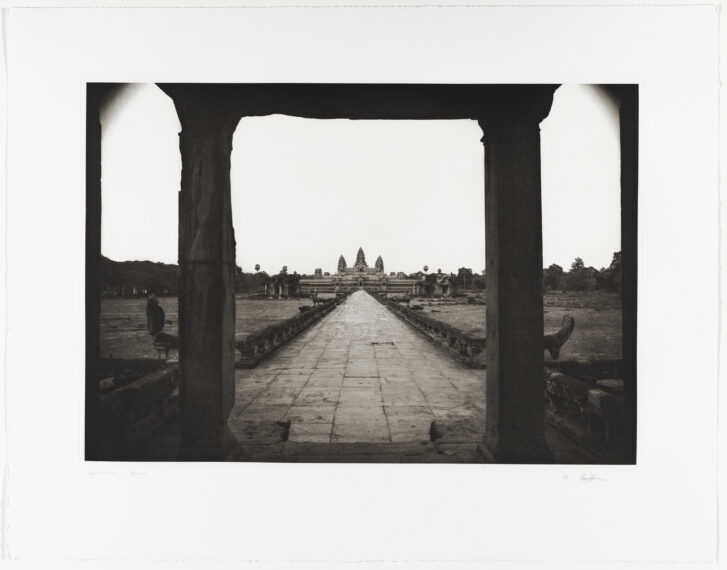

“Site Lines” also features the work of contemporary photographers, including Kenro Izu, whose photographs of the Cambodian temple complexes of Angkor Wat and the vicinity, taken between 1993 and 1995, reveal some of the photographic conventions of his predecessors. They present both the monumentality and artistry of these structures, whether through close-up details of the delicate bas-reliefs or long views that include architectural framing to establish depth. Like the best classic landscape photographs, they provide immediate visual impact and invite slow looking.

Kenro Izu (Japanese, born 1949), Angkor 73, Bayon, 1994, from the portfolio Light Over Ancient Angkor, photogravures, printed 1996. Gift of Cy and Paula DeCosse, 2024.65.3.11

Horizon line, check. Foreground framing, check. Symmetry, check.

Kenro Izu (Japanese, born 1949), Angkor 4, Angkor Wat, 1993, from the portfolio Light Over Ancient Angkor, photogravures, printed 1996. Gift of Cy and Paula DeCosse, 2024.65.3.1

“Site Lines” includes color images too, confirming that although today’s photographers may take advantage of modern technology’s bigger toolbox, they often return to familiar, timeless views. Richard Misrach has devoted much of his career to photographing landscapes, often focusing on human-made changes within them. His Sounion, Greece (Star Trails), part of his series of ancient Greek and Roman ruins, shows the Temple of Poseidon (5th century), about 40 miles south of Athens. As in 19th-century photographs, the angle and focus emphasize the renowned temple’s scale. But Misrach’s use of flash photography and long exposure allowed him to show the complexities of the marble columns at night and reveal the trails of stars, a view Scottish painter David Roberts might have envied.

Richard Misrach (American, born 1949), Sounion, Greece (Star Trails), 1979 (printed 1985), from the portfolio Graecism: Photographs of Ancient Greek and Roman Ruins, 1978–82, color coupler print. Gift of John and Beverly Rollwagen, 99.203.21

See More at Mia

“Site Lines: Photographing Historic Spaces” is on view in the Perlman Gallery (G368) through April 12, 2026.

You can see the precursors to the photographs in “Site Lines” in “Along the Nile with David Roberts,” on view in the Winton Jones Gallery for Prints and Drawings (G344), through June 7, 2026.