The Personalities Behind Mary Sully’s “Personality Prints”

By Laura Silver

August 7, 2025—Mary Sully, the groundbreaking Native American artist, channeled her life experiences and her fascination with American celebrities into what she called her “personality prints,” abstract triptychs she created between the late 1920s and mid-1940s.

Many of the celebrities she chose for her portraits are obscure or even forgotten to us today. But they struck a chord in Sully and served as muses to the reclusive, awkward woman whose art remained hidden until just a few decades ago.

We may not know why Sully chose these personalities, but we do know that her portraits all follow a similar pattern: three panels stacked vertically. The top panels use simple forms to represent key ideas about the chosen personality. The middle panels transform the metaphor into modernist, kaleidoscopic patterns. The bottom panels, always the smallest, refine the central idea through abstract forms that reflect the influence of Native American artistic practices, such as beadwork and quillwork.

Here’s a closer look at some of the personalities Sully chose to immortalize in her personality prints. What are your theories about Sully’s fascination with these luminaries of yesterday? Whom would you choose to portray in a personality portrait?

Jane Withers (1926–2012)

Child actor Jane Withers was the Elphaba to Shirley Temple’s Glinda, or maybe the Velma to her Daphne. Either way, while Temple—Hollywood’s top box office attraction of the Great Depression era (1929–39)—was all blonde ringlets, sunshine, and the Good Ship Lollipop, Withers was the brash, funny antidote. She played tough, bratty tomboys in films with titles like The Holy Terror (1937) and Always in Trouble (1938). In Bright Eyes (1934), she runs over Temple with her tricycle.

Withers was nearly as popular as Temple, too. Sales of Jane Withers merch—paper dolls, hair bows, socks, even mystery novels (think Nancy Drew)—earned her more money than her movies. Withers’s outsider persona, and perhaps the sensational news that she had received kidnapping threats in 1936, may have resonated for Sully. Her personality portrait of Withers includes symbols of safety, home, and love.

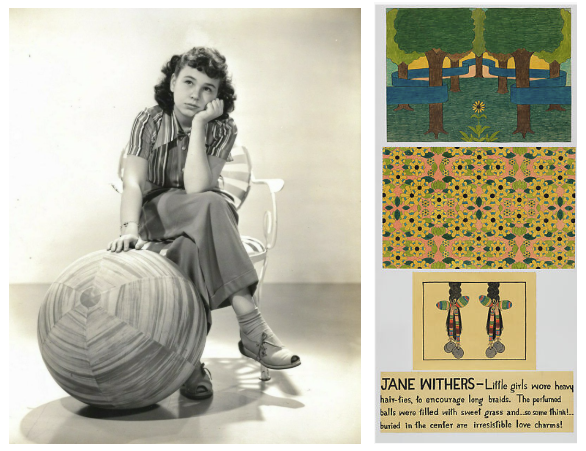

Left: Jane Withers in a publicity still, c. 1930s. Photo: Gene Kornman. Right: Mary Sully, Jane Withers, c. 1920s–1940s, colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Courtesy of the Mary Sully Foundation.

Charles Proteus Steinmetz (1865–1923)

German-born celebrity scientist Charles Steinmetz was a pioneering electrical engineer and mathematician known for his work in alternating current (AC) systems, which shaped the electrical infrastructure of the modern world. A brilliant outsider figure in the vein of Stephen Hawking (he had a physical disability), Nikola Tesla (he was an immigrant), and Doc Brown (he was a tad eccentric), his work earned him the nicknames “Forger of Thunderbolts” and “The Wizard of Schenectady.”

Steinmetz truly was one-of-a-kind. He had dwarfism, and despite his longing for children and family life, gave up those opportunities to avoid passing on his disability. Instead, he adopted his loyal lab assistant and opened up his home to the man’s family, becoming a grandfather to his children.

His captivating life story propelled him beyond the world of science into bona fide pop culture territory. And it likely moved Sully. Her portrait of Steinmetz features blue energy waves, arrow-like cross currents, and Dakota patterns reflecting cosmological energy.

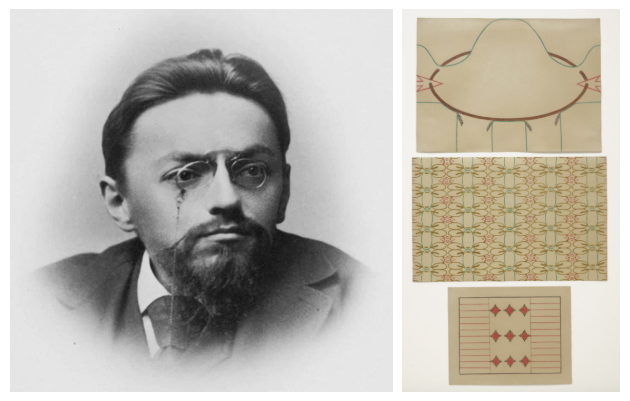

Left: Charles Steinmetz, c. 1900. Photo by White Studio (Schenectady, N.Y.), Collections of The Henry Ford, Object ID: 36.773.11. Right: Mary Sully, Steinmetz, c. 1935, colored pencil on paper. The Driscoll Art Accessions Endowment Fund and bequest of Virginia Doneghy, by exchange, 2023.56.6.

Anna Pavlova (1881–1931)

Anna Pavlova was one of the most celebrated ballerinas of the early 20th century. She was best known for The Dying Swan, a solo performance choreographed for her, which she performed about 4,000 times in her career. Born into poverty (her mother was a washerwoman), Pavlova was a frail and sickly child. But she would become a principal artist of the Imperial Russian Ballet and the first ballerina to tour around the world, which she did, in venues large and small, until her tragic death at age 49.

Perhaps Sully saw one of Pavlova’s many performances in New York City or read about her charitable works—Pavlova founded a home for Russian refugee orphans in Paris in 1920—or love of animals and birds. The ballerina kept pet swans at her home in London, including one she called Jack. In Sully’s personality print, an abstracted swan appears in the shimmering water and takes flight into the tall green grasses, perhaps ascending to heaven.

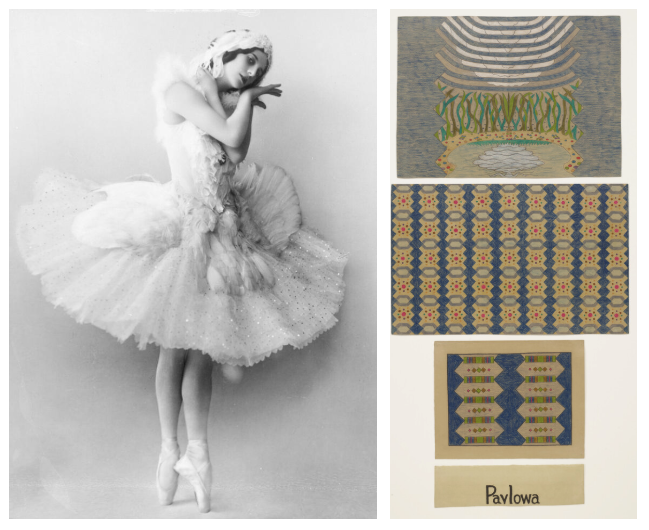

Left: Anna Pavlova as the Dying Swan, c. 1905. Right: Mary Sully, Pavlova, c. 1935, colored pencil and pigments on paper. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of the Mary Sully Foundation, 2023.56.7.

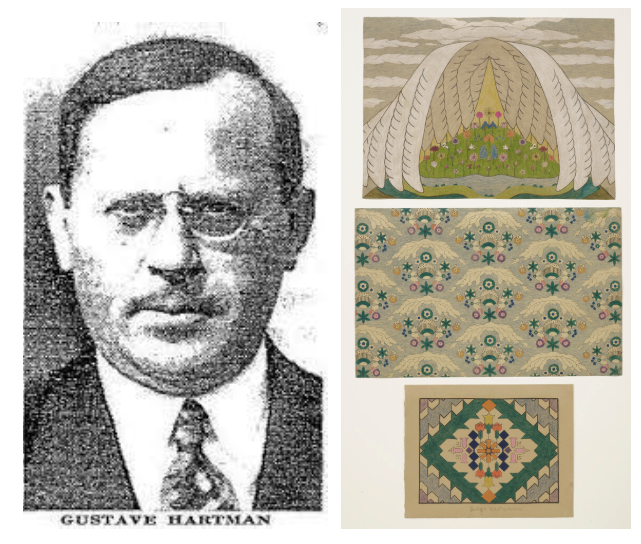

Gustave Hartman (1880–1936)

A Hungarian immigrant and noted New York City judge, educator, activist, and philanthropist, Gustave Hartman devoted his life to Jewish causes. In 1913, he established the Israel Orphan Asylum, on the Lower East Side, as a haven for children ages 1 to 6, many of them war orphans. He financed it out of his own pocket and with elaborate fundraising.

When Hartman died in 1936, at age 56, the New York Times reported that community members were so distraught that the “twelve hundred who attended the [funeral] service in the temple refused to leave to make room for invited mourners. … The throng was so great on Second Street that 85 policemen were needed to make room for the procession.”

We don’t know if Sully ever visited the Lower East Side or merely read Hartman’s obituary in the Times. But her metaphor for Hartman is a white amphitheater that shelters young plants, allowing them to grow.

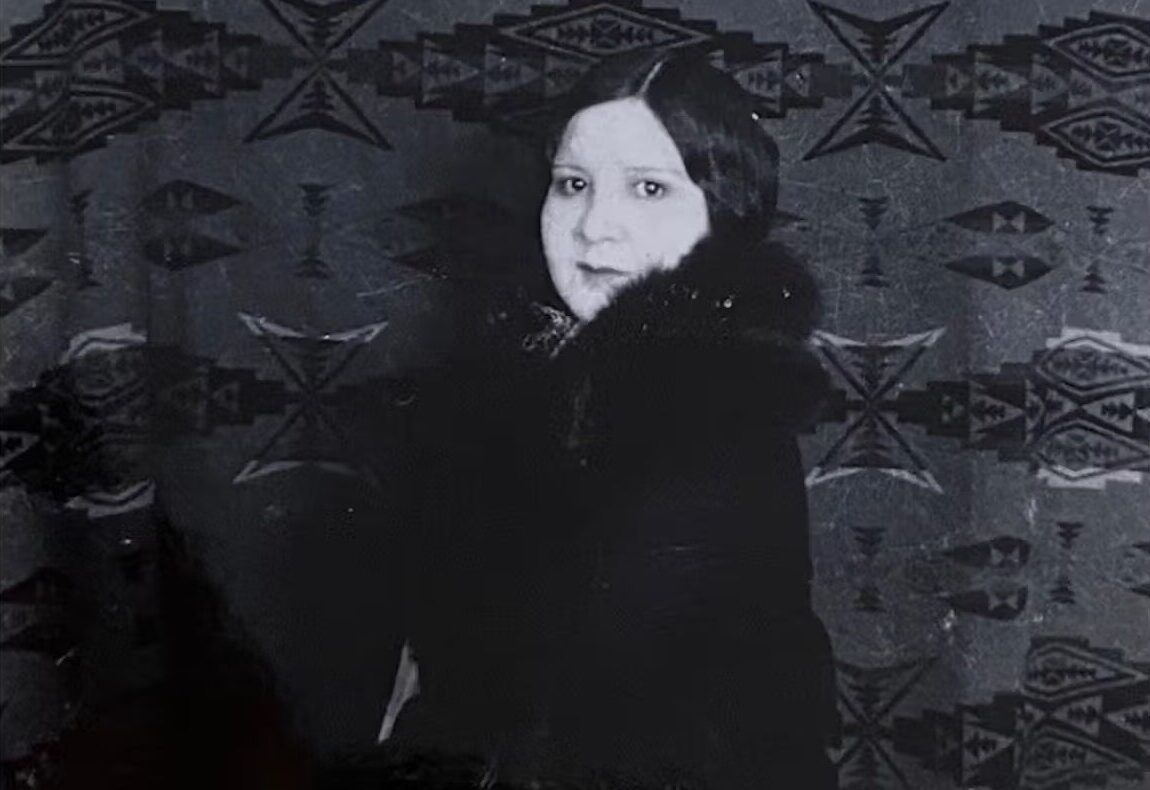

Left: Gustave Hartman, 1930s. Right: Mary Sully, Judge Hartmann, c. 1935, colored pencil and pigments on paper. Gift of the Mary Sully Foundation, 2023.56.3.

Anton Lang (1875–1938)

Anton Lang was a German potter and an actor in the Oberammergau Passion Play, a theatrical pageant depicting the last days of Jesus Christ that is still performed to this day. It started in 1634 in the Bavarian town of Oberammergau, fulfilling a promise villagers made to stage the play every 10 years if God spared them from the Bubonic Plague. Lang played several characters, including the role of Jesus in 1900, 1910, and 1922.

In the early 1920s, Lang toured the United States with other members of the troupe to draw attention to starving children in Germany. The press portrayed him and his countrymen as “simple, kindly peasants” who were dazzled by the sights of New York. Lang told reporters that playing Jesus had kept him on the straight and narrow. “It is as if one had taken up a priestly existence and could not do anything unworthy.”

Sully, herself deeply religious, presented Lang by drawing on Dakota religious imagery and depicting a path, perhaps of spiritual exploration.

Left: Anton Lang as Jesus in the Oberammergau Passion Play of 1900. Right: Mary Sully, Anton Lang, c. 1935, colored pencil on paper. Gift of the Mary Sully Foundation, 2023.56.5.

View Sully’s Work at Mia

Sully’s vivid, intricate drawings can be seen, and pondered, at Mia in Mary Sully: Native Modern, on view through September 21, 2025.