Print Study Picks: What the Weirdening Left Out

By Lori Williamson

October 17, 2025—I come to enhance “The Weirdening of the Renaissance,” not to steal the exhibition’s thunder. (With apologies to Marc Antony from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.)

In the early days of the Renaissance, artists emphasized order. Inspired by ancient Roman architecture and sculpture, they created structured compositions and statuesque figures that evoked lofty, rational thought. Then, new ideas began to emerge. In 1506, the excavation of the ancient Laocoön sculpture, depicting the Trojan priest and his sons writhing as they’re attacked by sea serpents, released Renaissance figures from static poses. Artists began to manipulate the science of perspective and often dropped the idea of representing the world as seen through a window. Earthy and outlandish thought flourished. Many images became just plain weird. With their creativity unleashed, artists left to us the joy of strangeness.

When Mia curators plan an exhibition, space constraints in the galleries often necessitate cuts to the list of works that end up in the show. Sometimes, though, it’s less a question of space and more one of thematic resonance. In this case, that meant carefully assessing each piece with the essential question—is it weird enough?

In this edition of Print Study Picks: an exclusive look at a few pieces that, while undeniably weird, did not make the cut for “The Weirdening of the Renaissance” exhibition.

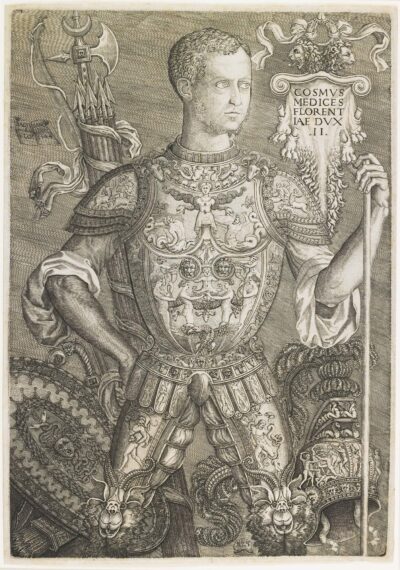

Niccolo della Casa; after Baccio Bandinelli, Cosimo I de’ Medici, 1544, engraving. Gift of Herschel V. Jones, 1926, P.10, 879

Few Renaissance portraits rival Cosimo I de’Medici for its sheer heavy metal presence. Look at this guy! His knee coverings alone will mess you up! His hair says, “Yeah, I am made in the image of Caesars, want a piece of me?” Facial hair? Just enough to be confusing. Weapons galore? Check.

Cosimo, the grand duke of Tuscany, had just conquered Florence and was heading to Siena. This portrait was a warning to get out of his infamously moody way. Symbols of his dynasty (both in reality and ambition) abound in this engraving—most prominently, the beribboned diamond ring in the upper right corner, which was a Medicean emblem representing the durability of the family’s reign. Rock on, Cosimo.

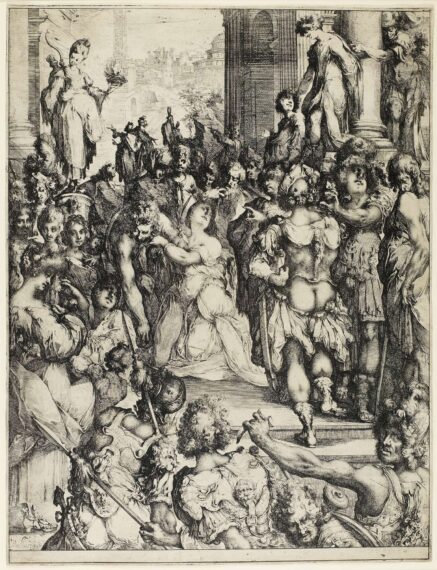

Jacques Bellange, Martyrdom of Saint Lucy, c. 1613–16, etching and engraving. The Putnam Dana McMillan Fund, the Winton Jones Endowment for Prints and Drawings, and gift of funds from the Print and Drawing Curatorial Council, 2008.55

Where to start with this wild scene? Did Saint Lucy have the highest number of witnesses to her martyrdom in history? This print would make one believe so—at least 37 individuals are crowding this scene, with different facial expressions, gestures, and clothing choices (or lack thereof).

The story goes that Roman guards came to take Saint Lucy away, but she could not be moved from the spot where she stood, not even by a team of oxen. Firewood was gathered to burn her in place, but the wood refused to burn. Finally, she was stabbed in the throat.

The artist used an inventive technique to produce rich gradations of tone through crosshatching and multiple immersions of the copper plate in the acid bath. To depict flesh, he stippled the surface with delicate dots. It all adds up to a work bursting with people, yet somehow otherworldly.

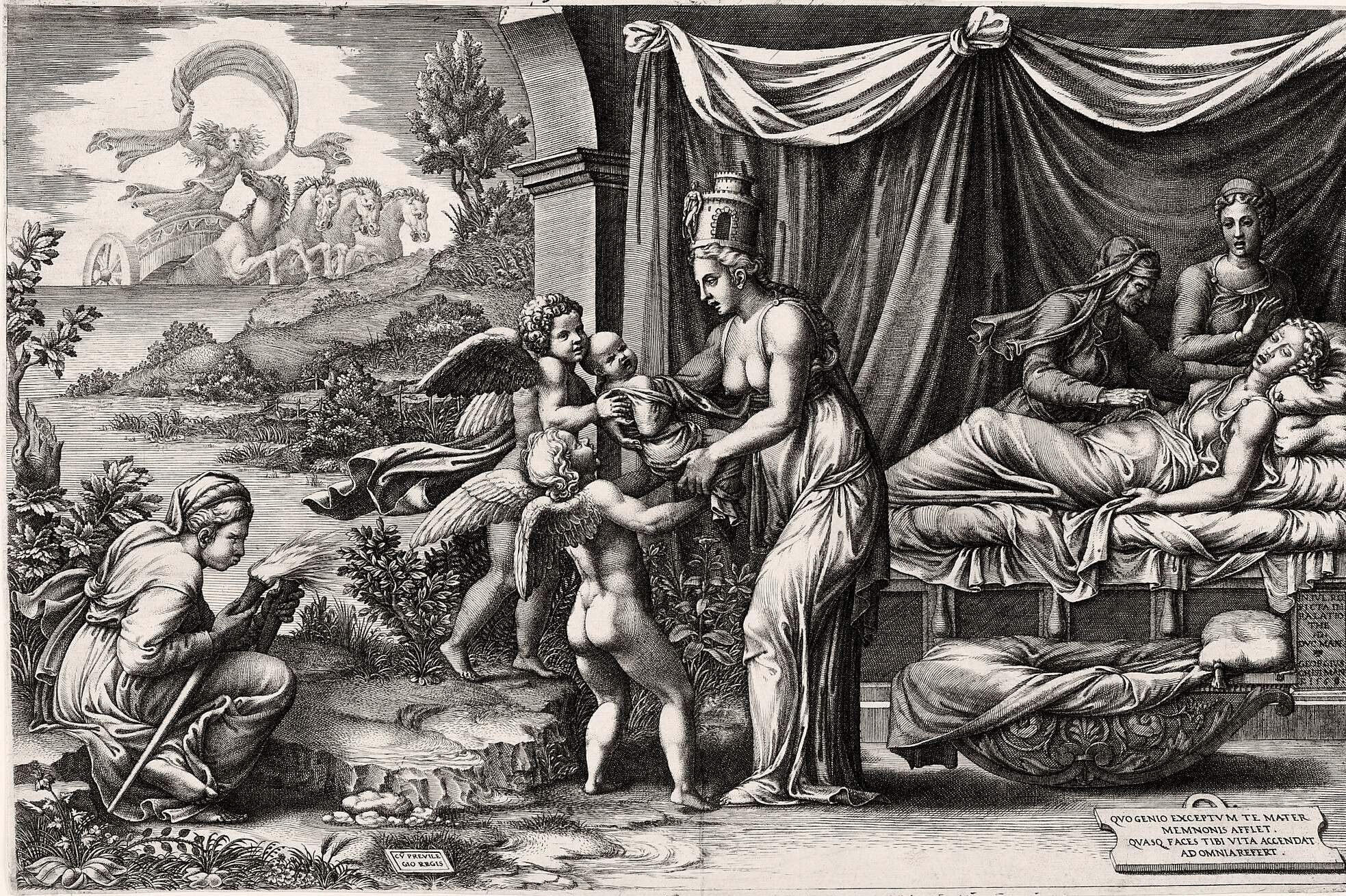

Anyone who has been part of the birthing process knows that it’s a truly weird experience.

In the middle of Allegory of Birth, winged genii hand a newborn to a personification of fertility or nurture. To the right, a mother appears to pass away after childbirth, watched over by a young and an old midwife. At left, a flame passes from one torch to another, and in the background, Apollo’s chariot brings a new day. Here is the circle of life in all its detailed glory and horror; allegories can be rough.

Bonus: What are genii? These medium-sized winged beings are often regarded as guardian angels. Contrast with putti (smaller and cuter), genii can typically be observed frolicking in works of art without directly impacting the scene.

Wondering what was weird enough to make the exhibition? “Weirdening of the Renaissance” is on view through November 30, 2025, in the Winton Jones Gallery (344).

About Lori Williamson, Supervisor of the Herschel V. Jones Print Study Room at Mia

Lori Williamson creates mini-exhibitions and teaches classes and Print Study Room visitors about the museum’s rich collection of works on paper. She’s the primary caretaker for more than 40,000 prints, 6,000 drawings, and 600 artists’ books, collaborating with curators in American, European, and Global Contemporary Art to make these holdings accessible. Williamson supports scholars through research and inquiry, and advocates for the inclusion of works on paper in exhibitions, social media, and outreach, helping to connect diverse audiences with this dynamic collection.

Lori Williamson creates mini-exhibitions and teaches classes and Print Study Room visitors about the museum’s rich collection of works on paper. She’s the primary caretaker for more than 40,000 prints, 6,000 drawings, and 600 artists’ books, collaborating with curators in American, European, and Global Contemporary Art to make these holdings accessible. Williamson supports scholars through research and inquiry, and advocates for the inclusion of works on paper in exhibitions, social media, and outreach, helping to connect diverse audiences with this dynamic collection.

Interested in seeing something in the Print Study Room? All are welcome by appointment. Email Lori Williamson and copy the Print Study Room to make an appointment.

Meet the other curators in the Department of European Art.