Artists in Charge: 50 Years of MAEP

By Tim Gihring

September 16, 2025—In the winter of 1975, a couple dozen artists from around Minnesota gathered at a conference center in the Minneapolis suburb of Wayzata, on the frozen shores of Long Lake. They were joined by arts funders and administrators, who assumed the artists would ask them for money.

The artists had other ideas.

“There was a lot of interest in controlling our own destiny,” remembers Tom DeBiaso, a photographer and filmmaker who was teaching at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design at the time and attended the meeting.

“The Vietnam War was ending, the youth revolution was happening, everything was being questioned. A lot of people wanted a seat at the table.”

The ultimate table was a museum. For decades, Mia and the Walker Art Center—the two major art museums in town—had taken turns hosting the Minnesota Biennial, a showcase for local artists. That is, if a curator invited you to submit your work and out-of-state judges selected it, a process that could feel like squeezing in through a window. By the 1970s, artists were over it.

So were the museums. Both had recently reopened after major, more modern additions; they were ready for something new. For the Walker, that meant burnishing a growing international reputation for avant-garde contemporary work. For Mia, that meant turning toward the community.

Ruth Hemlecker, the assistant director of Mia at the time, joined the Wayzata gathering and noted the artists’ various desires: space, autonomy, recognition.

“The museum had that impulse to engage the artists,” DeBiaso says, “thinking about a new way for artists to get from the studio through the walls of the museum.”

By the end of the meeting, a consensus had emerged: What would happen, as DeBiaso puts it, “if artists selected their own work, based on their own expertise and vision and community,” and showed it at Mia?

There were no real precedents at other museums. It was, as Hemlecker would later say, “a revelation.” In the spring of 1975, the artists sent Mia a formal request for a dedicated gallery space, run by local artists for local artists.

“An appropriate place to exhibit,” Hemlecker said, “where they would be treated with respect and dignity.”

The museum agreed, and the first show of the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program (MAEP) went up that December. Nearly two dozen artists (DeBiaso, George Morrison, Judy Onofrio, and most of the others at the Wayzata conference) exhibited under the rather unwieldy, very ’70s title of “State: State of the Art. Art: Art of the State.” The opening celebration featured beer and pretzels.

Since then, the MAEP has given space to more than 3,000 artists from across the state. The youngest was 6, when Oakley Tapola showed with her parents, Bruce Tapola and Melba Price, in 1993. The oldest was Lillian Colton, who was 93 when she displayed her seed-art creations at Mia in 2004. There were live ants in an MAEP show in 1985, live chickens in 2000.

“The chickens were taken home every night,” says Nicole Soukup, the current MAEP supervisor at Mia.

After 50 years, there is still no other program like it at a major museum. And it still provides that seat at the table. “It’s always had a reputation as a stepping stone, a launching pad,” says Soukup. “But mostly it’s been artists championing other artists.”

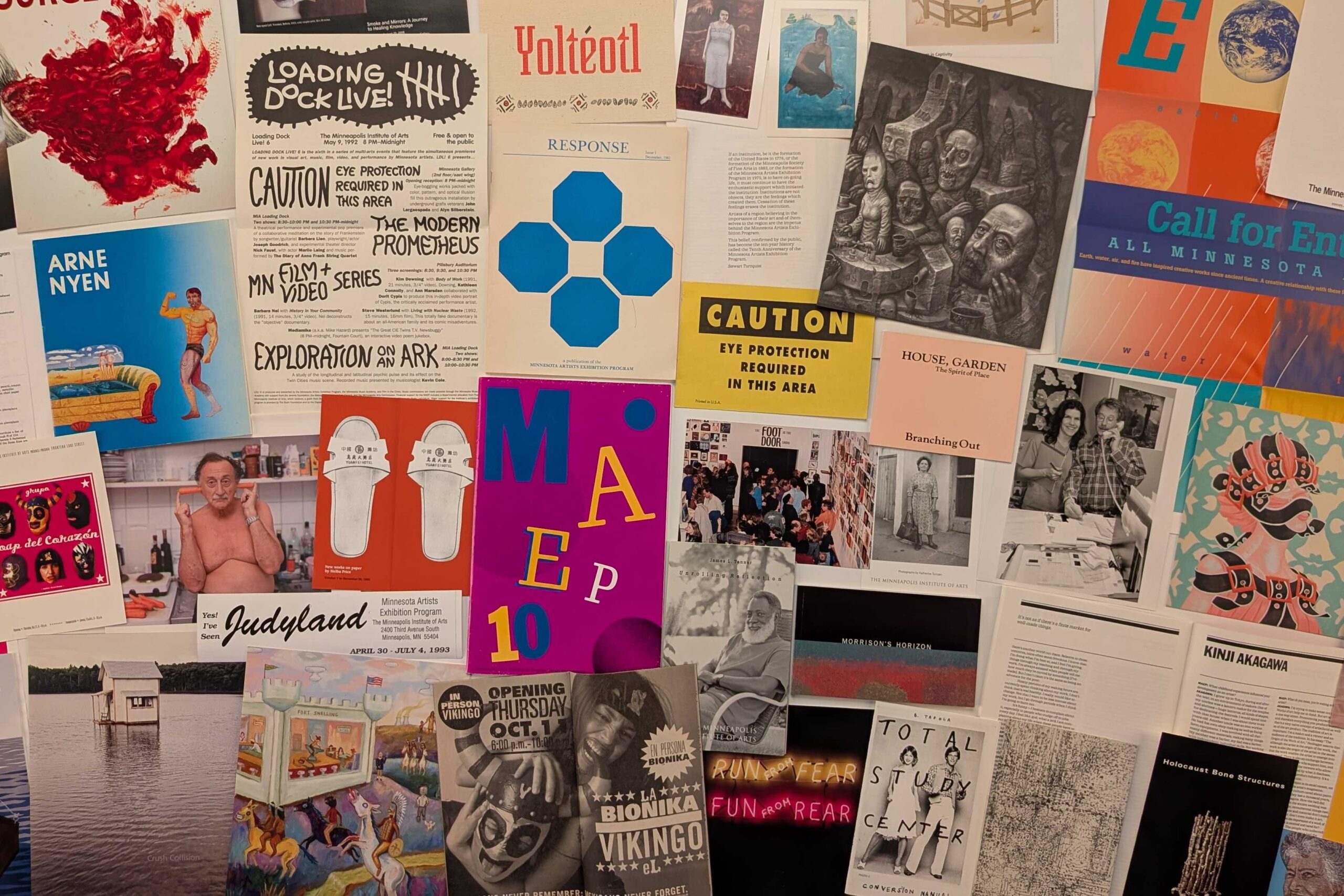

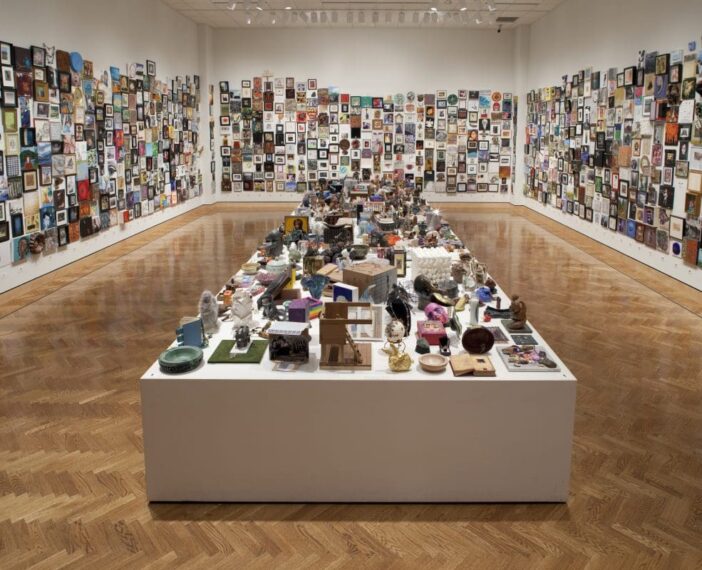

The 2010 “Foot in the Door” show, organized at Mia by the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Program and open to anyone.

Opening a Door to Connection

Exactly how artists would be chosen for MAEP shows, in the absence of a curator, led to an unusual system at first. Artists were asked whose work they would like to highlight, and the names were fed into a primitive computer.

“The computer would match people and spit out an exhibition,” DeBiaso recalls. It was meant to be neutral. “It didn’t work,” DeBiaso says.

Eventually, the idea emerged of selecting a panel of artists, who in turn would select artists for exhibitions, based on submitted proposals. An MAEP coordinator—not a curator—would oversee the process. The shows, then as now, included gallery talks and opening celebrations, which quickly became must-see events. Concerts in the loading dock, dance parties in the gallery.

Indeed, much of the creative programming that is now standard fare at the museum—free evenings with food and music, outside partners, even the spirit of “everyone is welcome,” Soukup says—began with the MAEP. This shift toward playful inclusion is perhaps best embodied in the once-a-decade “Foot in the Door” show, which features anyone whose artwork can fit into a one-foot-by-one-foot square box. It began, in 1980, as a five-year celebration of the MAEP.

“These things are so embedded now that we take them for granted as part of the culture,” Soukup says. “But the MAEP has always been this incubator both for artists and the institution.”

Pao Houa Her; Untitled (Veterans 3), 2014; archival pigment print

For the artists, an MAEP exhibition has often been career-changing, even life-changing. Pao Her, a Hmong photographer from Saint Paul, was encouraged to apply for an MAEP show in the early 2010s by the program coordinator at the time. She had been photographing Hmong veterans of the Vietnam War, who fought with the Americans but were never officially recognized by the U.S. military.

In 2015, she got the show: “Attention,” featuring 10 portraits in gilded frames of former soldiers in uniforms and regalia scraped together from second-hand stores. “What does it mean to honor somebody or an object in the space of a museum?” Her says of her intention.

Some Hmong leaders feared pushback, given the political debates at the time around “stolen valor.”

“I liked the idea that there was tension in this space,” Her says. “It was my first attempt at thinking about my work more conceptually.”

Now that many of the veterans have passed on, Her says, their families often request the portraits as mementoes.

“I think a lot about that show, to have had that stage. It offered the first real possibility of what an artist career could look like for me. And now the show continues to give new layers to this work.”

Tia Keobounpheng with her 2023 MAEP show, “Revealing Threads.”

Tia Keobounpheng, an artist of Finnish and Sámi descent who was born on Minnesota’s Iron Range, was just becoming known for her intricately embroidered tapestries when she opened “Revealing Threads” in the MAEP Gallery in 2023. The show merged her unique style with traditional textile techniques from her family’s homeland, documenting a new understanding of her roots.

“My worldview was shifting as I considered what it means to come from an Indigenous people,” says Keobounpheng, who has gone on to show in galleries across the country. “Mia and the MAEP opened the door for visitors, collectors, institutions, and the community to connect with my work and invest in me as an artist. It changed my life.”

Learn More about the MAEP

“MAEP: Celebrating 50 Years of Minnesota Creativity at Mia” is a free party on October 10, 2025, in the Target Reception Hall to honor the past five decades of exhibiting local artists’ work at Mia and raise a toast to many more. Register and find more information on the event page.

The current MAEP show is Hend Al-Mansour’s “Mihrabs: Portraits of Arab American Women,” on view through October 26, 2025.