The Material World of Sopheap Pich

By Tara Kaushik

January 6, 2026—Sopheap Pich was unsatisfied with painting. His training at the Art Institute of Chicago had focused on it, but something felt lacking.

“I found painting insufficient,” he says. “Painting is a bit of an abstract activity. You are basically creating something on a flat surface that wasn’t there before. I didn’t know what I was doing with painting.”

In 2004, two years after returning to his native Cambodia, he began experimenting with sculpture, and something clicked. It was a medium, he says, that felt more in harmony with the local context, where artisanship abounded. He used what was cheaply and readily available around him—bamboo, rattan, and metal wire.

“It felt right—the activity of making a sculpture felt more real to me than painting did,” he says. “There’s a progression—you start here, and then you end up here. And during that time span, there’s a certain emotion that was involved, in terms of making this object.”

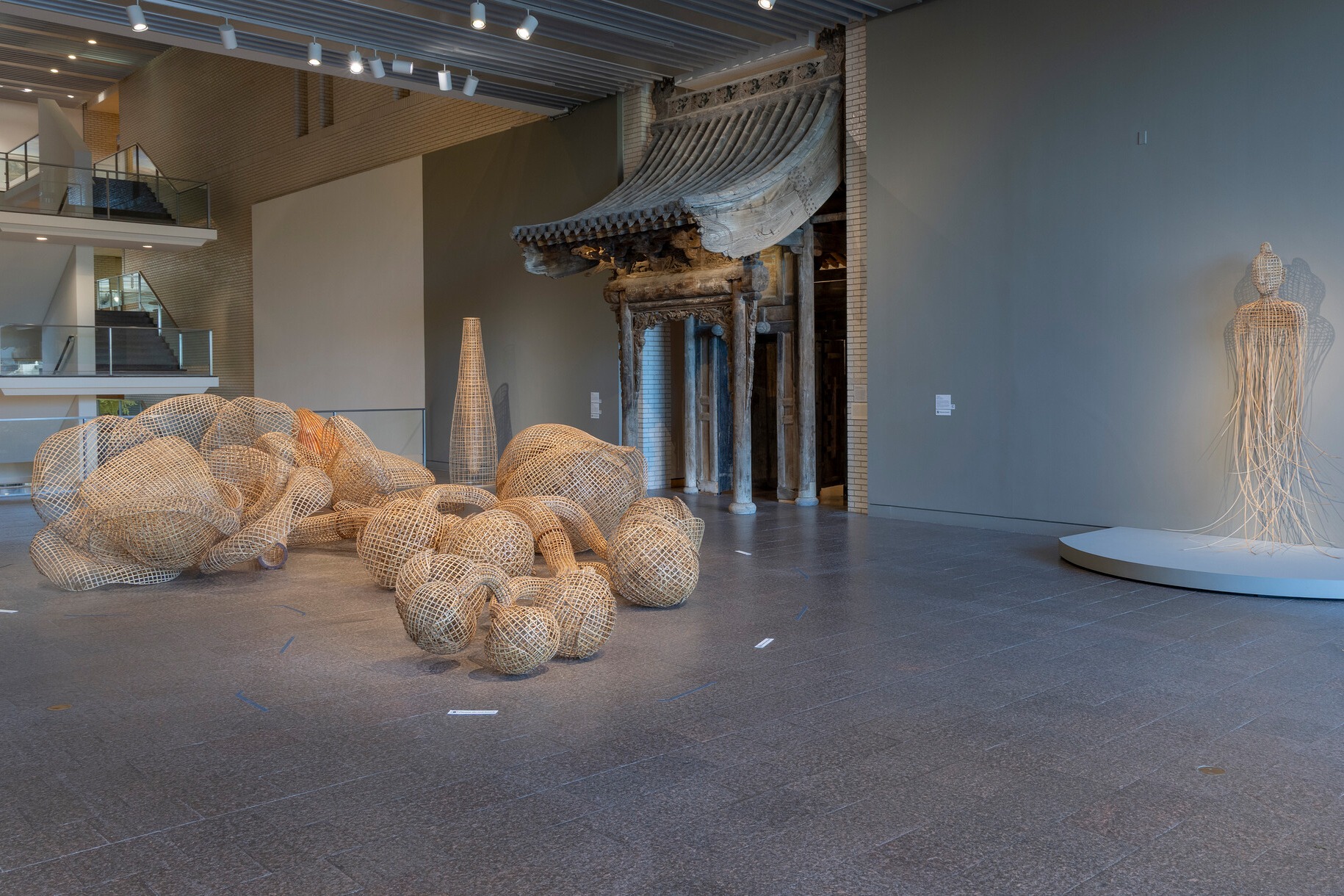

Today, Pich is one of the most celebrated contemporary artists in Southeast Asia. His exhibition “In the Presence Of” presents four large-scale artworks, all on loan to Mia. The sculptures pose something of a paradox—they’re voluminous, taking up most of the gallery, yet transparent, allowing light to pass through a grid-like weave. They look delicate, even fragile, composed of swooping, dancing lines, but they are actually quite durable.

Grounded in Place

Bamboo and rattan are among the most essential and versatile resources in Cambodia, playing a critical role in local communities and businesses. Both plants are abundant and widely used, for everything from building materials to food and medicine. They’re also crucial to the health of Cambodia’s forests and their unique biodiversity, as they support other plants and animals in the ecosystem.

Pich employs traditional Cambodian weaving techniques in his art, evoking the baskets, fish traps, furniture, and agricultural tools that are made locally from bamboo and rattan. He notes that using such commonplace materials allows him to “think freely and intuitively,” creating works that resonate with his experiences and surroundings.

Using sustainable materials isn’t the only way Pich connects his artistic practice to his community. Since returning to Cambodia in 2002, he’s worked with a team of about 10 studio assistants, whom he considers family. As one curator put it, “At the foundation of Pich’s artistic practice resides a community spirit.”

The Process Is the Medium

Pich describes his creative practice as being about “the slow labor of making something from nothing.” He creates his sculptures by hand, using minimal tools. It’s painstaking, meticulous work—bamboo is a rigid plant, and to make it pliable and easier to manipulate, it must first be harvested or salvaged, then washed, boiled, bent, woven, and tied with wire. The process is repetitive and meditative.

“You’re in another world,” he says. “You’re in another space. And the only thing that you worry about is food and sleep.”

Eventually, the sculpture reveals itself.

Infinite Possibilities

Discussions of Pich’s work inevitably involve evocations of the brutality of the Khmer Rouge, which his family fled in 1979.

“It’s a reference I find too limiting,” says the artist. “While certain works have relation to that time of my life, I think of the objects I make as possessing potential for energy and a sense of discovery. I believe that the expression of labor and time through my art will lead to some kind of freedom.”

View of “Caged Heart” (L2017.145a,b) installed in Sit Investment Associates Gallery (G200) at Mia for the exhibition “Sopheap Pich: In the Presence Of.” The exhibition is on view through February 1, 2026.

Pich’s works resist easy categorizations. The sculpture Caged Heart offers an example. It’s one of several by the artist that depict human organs, including some of his earliest works, which captured a pair of lungs and a stomach. The visual effect is striking: the rawness of the subject matter reflects the material from which the work is made.

The work could be interpreted in a couple of ways—a reference to the artist’s youthful intent to study medicine or to the Cambodian idea of good and bad hearts, a cultural belief that plays a role in describing and judging the moral character of individuals and members of different sectors of society.

Pich offers yet another interpretation in a recent interview with ArtForum.

“If you’re driving on the road in Cambodia, it’s almost like you’re traveling along a body; the chest is split open, and the insides are spilling out,” he says. “Most shops here don’t have doors—they have corrugated sheets of metal that get rolled down at night. Everything seeps out onto the streets. People live their lives in plain view: You see what they sell, what they fix, what they create. I’m trying to make my work operate in a similar fashion. I want it to be less timid—I want the insides of my art to be on the outside.”

In Conversation with the Artist

On Thursday, January 8, 2026, join us for a lecture and conversation with artist Sopheap Pich. Following his presentation, Leslie Ureña, Mia’s Associate Curator of Global Contemporary Art, will join Pich for a discussion about the many states of transition present in his practice. Free tickets are available.

“Sopheap Pich: In the Presence Of” is on view until February 1, 2026, in the Sit Investment Associates Gallery (200).