American Scenes

Lesson Objective

Students will explore the diverse American landscapes through the experiences of five artists by close observation, discussion, and art making.

Introduction

Artists throughout history have captured their perspective of the natural and human-built environments around them. We all have different lived experiences that shape our own unique responses when we view artwork.

As a class, make a T-chart or discuss examples of what is a natural versus human-built environment in your city (e.g., the Mississippi River is natural, the playground is human built). Start with a relatable surrounding (e.g., school, city, local park, neighborhood). When you’re ready, choose one of the five regions in the Core Ideas section and discuss what in that environment looks to be natural versus human built.

Warm-Up Exercise

Think about what you see on your way to school, sports practice or extracurricular activity, or your favorite park. Are there skyscrapers? Buildings? Cars? Trees? Open fields? Share with your class. If you lived in the country, how might your view change? As a class, keep track of your observations on a T-chart.

Background

Use the art activity on this page alongside one (or all) of the following American landscape examples. To learn more about each perspective, click on the Core Idea of your choice. If you wish to add creative writing or more art making to your lesson, scroll down to the Learning Extensions.

Core Ideas

- • The West

- • Rugged Coastline

- • Skyscrapers and City Scenes

- • Small-Town America

- • View from the Road

Art Activity

Guided Practice

Look at the image(s) from the region you selected. Take time and note the details of what’s included. What more can you find? What can we learn about the location from these artworks? What questions do you have? What are the differences and similarities of these natural and built landscapes to where you are?

Materials

- • Oil pastels and watercolor

- • Watercolor paper

- • Pencil

Procedure

- 1. After you’ve selected a region and read the background information, look at the artwork. What are some details that tell you more about that setting? Now, think of a landscape right outside your window or a favorite landscape. This could be in your city, from travels, or from your imagination.

- 2. Use a pencil on the watercolor paper to lightly trace out what you want your landscape to look like. You can make it look realistic or abstract.

- 3. Start with watercolor and paint your environment. Remember, this could reflect your city, from travels outside of your city, or it could be made up, too!

- 4. You’ll need to wait for the watercolor to dry. After it’s dry, add a layer of oil pastel to layer colors and texture to your landscape art for more detail.

- 5. After you’re done, write three to five sentences on the back that answer the following questions: Where is this? Why is this place important? Why did you choose this environment? What are some details in your artwork you wish to talk about?

Reflection

What can you learn from landscape art? How does the medium impact how you see different places? How does the medium impact how you feel about what you see? How does your artwork make you feel? What do you want your classmates to learn from your artwork? How would it look if you took a photograph of your place rather than create it using watercolor and oil pastel?

Learning Extensions

Send a Postcard | Creative Writing

Pick one of the scenes from the Core Ideas and imagine yourself there. Write a postcard to a friend describing your experience. What are your surroundings like? How do you feel being there? What kind of things might you be doing? Share the postcards and have classmates guess which scene is being described.

Travel Log | Writing and Artmaking

Ed Ruscha paid special attention to the buildings and signs he encountered when he traveled Route 66. If you go on a road trip, keep a travel log of the things you see along the way. Then create an artwork inspired by what you saw. You could also take notes and make art about what you see if you ride a bus or train.

Compare and Contrast Scenes | Learning to Look

Select an artwork from one region, then select another artwork from a different region. Place them side-by-side. Compare the similarities and differences with each other. If they are different mediums, how does that impact how you see it? This can be a class discussion or a writing assignment.

Minnesota State Standards

Social Studies

3.3.17.1 Describe how different places, including school, the environment, or local community, makes one feel.

4.3.17.1 Analyze how different perspectives have influenced decisions about where to locate and what to name places.

5.3.16.1 Describe how the choices people make have impacted a physical environment over time.

Visual Arts

5.0.4.7.1–5.9.4.7.1 Respond: Analyze and construct interpretations of artistic work.

5.0.5.9.1–5.5.5.9.1 Connect: Integrate knowledge and personal experiences while responding to, creating, and presenting artistic work.

Core Idea: The West

Between 1820 and 1850, nearly four million people moved into the western territories of the United States. Settling this new frontier inspired many Americans with national pride and patriotism. They felt this was America’s divine destiny. And to people tired of living in overcrowded East Coast cities, the West offered resources that seemed unlimited—ore for mining, forests for lumber, and prairies for farming.

The federal government and enterprising businessmen sent survey teams and exploratory expeditions westward. Writers, photographers, and artists often went along to document these journeys. They created art that encouraged easterners to travel to the West or invest in its resources.

The painter Albert Bierstadt made his first trip west in 1858, joining a survey team heading to Colorado and Wyoming. He returned in 1863 and spent two months in Yosemite Valley, California. On all of his journeys, Bierstadt made field sketches, color studies, and photographs. Back home in his New York studio, he used those pictures—taking a sky from here and a mountain from there—to produce his final paintings.

In The Merced River in Yosemite, Bierstadt captured the majestic beauty of dusk (or maybe dawn) on the banks of the Merced River. Sunlight streaming through the trees washes the canyon with tints of gold and pink. The entire scene glows with sunlight reflected off wisps of low-lying clouds and the mist rising from the water. Although Bierstadt included several figures, they are not very important. The sky and mountains, rivers and trees, rocks and wildflowers are the real subjects of this painting.

Left: The Merced River in Yosemite, 1868. Albert Bierstadt, American, 1830–1902. Oil on canvas. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Mr. & Mrs. Atherton Bean in Memory of Douglas Atherton Bean. 81.6. Right, a detailed view of the painting

Core Idea: The Rugged Coastline

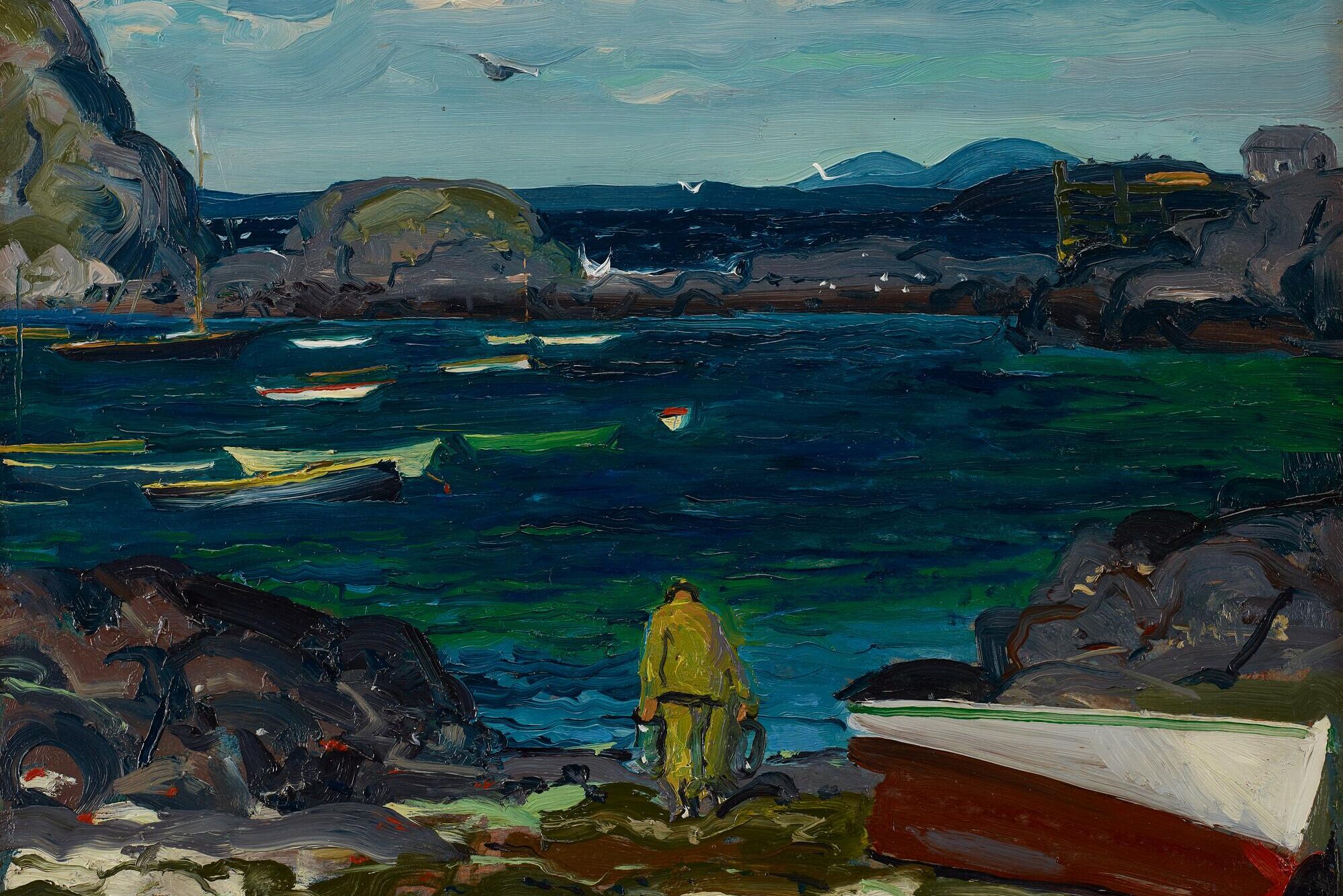

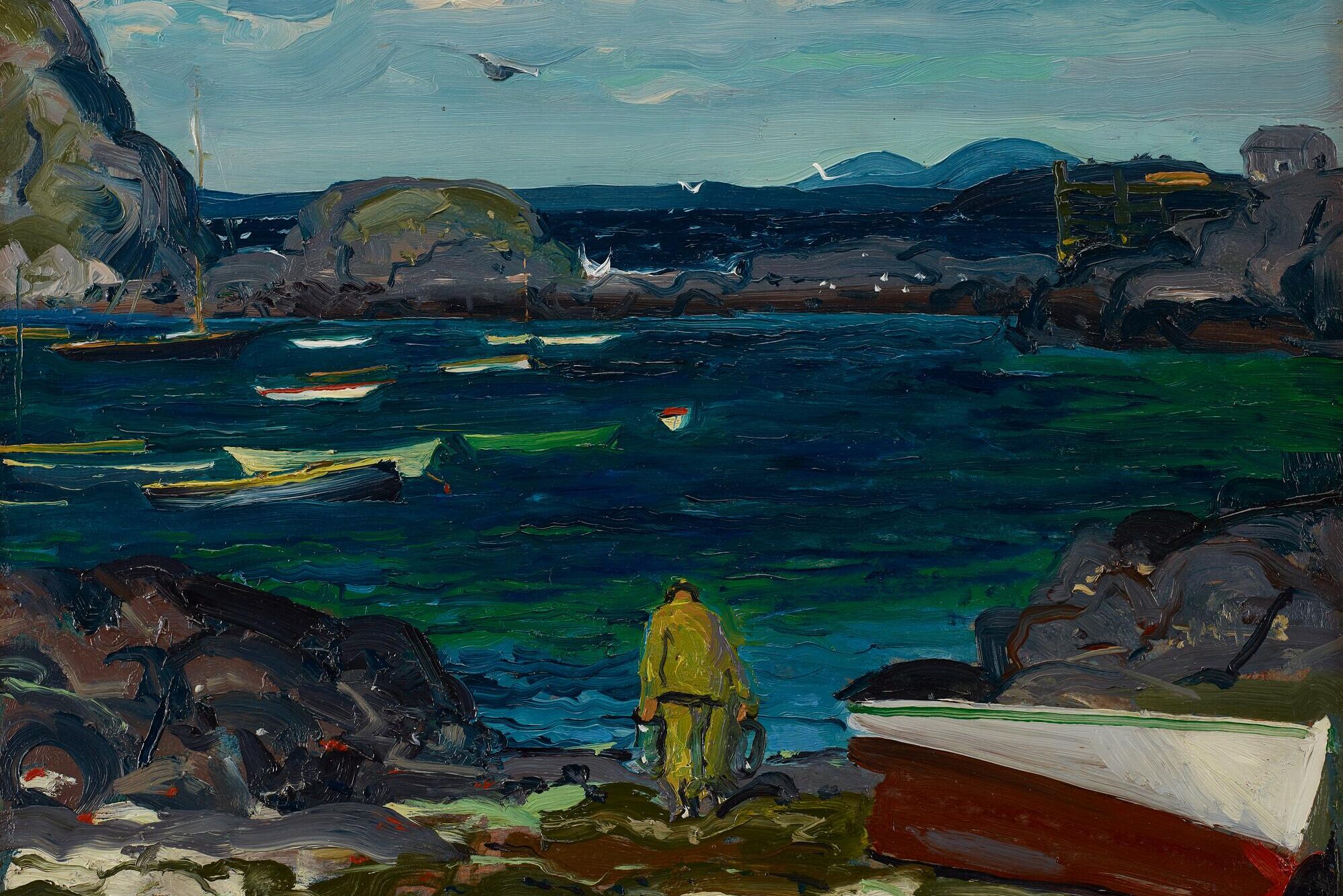

The Harbor, Monhegan Coast, Maine, 1913. George Bellows, American, 1882–1925. Oil on panel. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund. 33.16

Monhegan Island, off the coast of Maine, was a popular spot with artists in the 1800s and is still a haven for artists today. This tiny island only a little over a mile long has a spectacular coast, with rugged cliffs and crashing surf.

In 1911, at the invitation of his good friend and fellow artist Robert Henri, the painter George Bellows spent three weeks on Monhegan Island. Bellows fell in love with the place, describing it as the most wonderful country ever modeled by the hand of the master architect. He returned with his family in 1913, and during the summer and fall he worked furiously, painting more than 100 pictures, including The Harbor.

At the time Bellows stayed on Monhegan Island, the only people living there year-round were a few lobster fishermen and their families. In several of his seascapes, Bellows depicted their life and work. He knew about life by the sea. As a child, he had often visited his grandfather, who was a whaler in Montauk, off the coast of Long Island.

This painting presents a world of greens and blues, of rocky cliffs, brilliant skies, and boats floating on the harbor’s gentle waves. A fisherman wearing bright yellow gear trudges toward the water, carrying his lobster traps. Even from afar, you get the feeling his work is not easy.

Bellows was influenced by Winslow Homer, an American artist known for his seascapes.

The Conch Divers, 1885. Winslow Homer, Painter, American, 1836–1910. Watercolor, blotting, lifting, and scraping, over graphite on ivory paper. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund. 15.137

Core Idea: Skyscrapers and City Scenes

City Night, 1926. Georgia O’Keeffe, American, 1887–1986. Oil on canvas. Gift of funds from the Regis Corporation, Mr. and Mrs. W. John Driscoll, the Beim Foundation, the Larsen Fund, and by public subscription. 80.28. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1925, Georgia O’Keeffe moved into the Shelton Hotel in downtown New York. In this brand-new skyscraper, O’Keeffe and her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, had an apartment on the 30th floor. That high vantage point inspired O’Keeffe to paint the quickly changing cityscape of New York.

O’Keeffe’s cityscapes focused on skyscrapers. During 1925, 45 skyscrapers were built in New York, the most in one year. The skyscraper was very much an American symbol of modern technology. Many painters and photographers found themselves drawn to this new subject. From 1925 to 1929, O’Keeffe created 30 skyscraper pictures.

One can’t paint New York as it is, but rather as it is felt. O’Keeffe wanted people to sense the overwhelming size of the skyscrapers being built up around her. So she painted the buildings from unusual angles and perspectives. Her husband, who photographed the skyscrapers, may have influenced how O’Keeffe painted her cityscapes. When you look at them, you feel like you are viewing them from the ground, peering up through a camera lens.

City Night could even be called ominous. Two forbidding black skyscrapers look ready to topple onto each other or maybe onto us. A mysterious light (the moon? a streetlight?) shines into the slice of blue night sky between the buildings. Another skyscraper, bright white, appears in the distance. Its shape resembles that of the Shelton Hotel, O’Keeffe’s home.

New York at Night, 1934 (printed 1982). Berenice Abbott, Photographer, American, 1898–1991; Parasol Press Ltd., New York, Publisher. Gelatin silver print. Gift of the William R. Hibbs Family. 86.108.37. © Estate of Berenice Abbott / Howard Greenberg Gallery

Core Idea: Small-Town America

Portrait of James Agee, 1937. Walker Evans, Photographer, American, 1903–1975; The Double Elephant Press Ltd., Publisher. Gelatin silver print (printed 1974). Gift of Daniel, Richard and Jonathan Logan. 84.138.9. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

During the Great Depression, millions of people couldn’t find work. They fell into poverty and led hard lives filled with despair. Many American artists and writers felt an obligation to make the public understand the plight of the unemployed. Their efforts resulted in a new art form social documentary. Photography turned out to be one of the best ways of reporting the brutal realities of life in the 1930s.

The federal government recognized that photography could help bring about social change. In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created a program to aid thousands of farmers and sharecroppers who had lost their land and livelihood because of drought and financial hardship. This new government agency (later called the Farm Security Administration) hired photographers to document the living conditions of these rural workers. As the project grew, photographers were sent all over the country to record what was going on in the United States during the Depression.

Walker Evans was one of the first photographers in the program. He traveled to West Virginia and Pennsylvania and later to Mississippi and Alabama, documenting the land, crops, schools, stores, roadside stands, and churches. He also photographed the people and their houses and belongings. Evans made it his mission to record a subject exactly as he found it. He didn’t arrange his pictures to heighten their effect. And no matter how dismal or squalid the surroundings, his subjects are portrayed with dignity.

During the summer of 1936, Evans went to Greensboro, Alabama, with the writer James Agee. For several weeks the two of them stayed with three families of sharecroppers, recording their lives in words and pictures. Evans’s photographs became the illustrations for Agee’s book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, an eye-opening portrayal of the hardships these families endured.

Left: Floyd Burroughs’ Bedroom, Hale County, Alabama, 1936. Walker Evans, Photographer, American, 1903–1975. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Arnold H. Crane. 75.42.7. Right: Roadside Restaurant, Alabama, 1936. Walker Evans, Photographer, American, 1903–1975. Gelatin silver print. The William Hood Dunwoody Fund. 75.26.26

Core Idea: The View from the Road

Have you ever traveled along Route 66? Maybe not. Today, you can take big interstate highways when you want to drive across the country. But many years ago, Route 66, stretching 2,400 miles, was the main road from Chicago to Los Angeles. People called it the Main Street of America or the Mother Road.

Ed Ruscha traveled on Route 66 a lot. In 1956, when he was 18 years old, he moved from Oklahoma City to Los Angeles, taking that route. He drove with his friend Mason Williams in a 1950 black Ford sedan, and the two stopped often at gas stations to service the car. Over the years, Ruscha, who remained in Los Angeles, went back and forth many times along this famous highway.

His trips on Route 66 made a deep impression on Ruscha. The signs, billboards, and gas stations spotting the desolate highway inspired him to create a series of artworks. In 1963, he published a book entitled Twentysix Gasoline Stations, documenting his travel on Route 66 through black-and-white photographs of roadside gas stations. Ruscha made several paintings and prints from those photographs, including Double Standard.

Left: Twentysix Gasoline Stations, 1963 (second edition, 1967). Edward Ruscha, American, born 1937; Edward Ruscha, Author, American, born 1937; Edward Ruscha, Publisher, American, born 1937; Cunningham Press, Alhambra, CA, Printer. Offset printing; bound volume. The John R. Van Derlip Library Fund. B.97.6.1. © Ed Ruscha. Right: Double Standard, 1969. Edward Ruscha, American, born 1937; Mason Williams, American, born 1938; Edward Ruscha, Publisher, American, born 1937; Co-printed by Jean Milant, Printer, American, born 1943; Co-printed by Daniel Socha, Printer, American, 20th century. Color screenprint. The Francisca S. Winston Fund, by exchange. P.70.55. © Ed Ruscha and Mason Williams