Dragon Style: A Norwegian Silver Show Reveals the Nordic Spirit

By Tim Gihring

November 10, 2025—For hundreds of years, Norway was dominated by its neighbors—Sweden, then Denmark, then Sweden again. As the push for independence grew in the late 19th century, so did the search for a uniquely Norwegian identity. And in the 1880s it emerged: Dragestil, or Dragon Style.

It was a mash-up of Art Nouveau and the Viking Age, incorporating ancient motifs and materials (dragons, walrus ivory, scenes from Nordic sagas) into the contemporary vogue for flowing designs inspired by nature. In the Romantic Nationalist mode then dominating northern Europe, Dragestil was both nostalgic and progressive: in embracing its history, Norway hoped to rally behind its best instincts, both aesthetic and political.

“Crowning the North: Silver Treasures from Bergen, Norway,” now open in Gallery 350, traces the origins of this style in a medium that Norway made its own. Unlike most other European countries, which had to import silver from the Americas just to make currency, Norway had its own silver mine—with more silver coming in through trade. It could afford to use it for art. And it did, as the exhibition demonstrates, in myriad ways: bridal crowns, tankards, tableware, even miniature Viking ships.

Marius Hammer, Viking Dragon Boat, c. 1900, silver and enamel, Kode Bergen Art Museum, Bergen Silver Foundation, photo: Dag Fosse, Kode Bergen Art Museum.

The show begins in the early 1600s, as the North Sea city of Bergen was becoming a global crossroads. Ships arrived to haul away Norwegian timber, leaving behind tons of foreign coins, which were melted down and transformed into artworks. The craft attracted many of the best silversmiths and goldsmiths in Europe. By the late 1800s it was peaking—just as the country was asserting its national pride.

Some of the most compelling pieces in the show are by a Norwegian silversmith named Marius Hammer, who came from a long line of craftsmen. In the 1880s, his shop was the largest in Bergen, making everything from silverware to jewelry, ultimately focusing on high-end souvenirs.

Hammer dove deeply into Viking symbolism and, around 1900, came up with things like a silver dragon boat, enameled with colorful green, blue, and purple waves. A silver centerpiece from 1888 is topped with horse heads and incorporates a style of ancient ornamentation found in medieval stave church architecture.

When Norway finally won its independence from Sweden in 1905, Dragestil began to fade. The cause had been won. Modernism was settling in, shoving aside romanticism if not nationalism. By the time World War I erupted, even Hammer was pulling back, though a punch bowl he designed in 1915 uses walrus ivory—a classic Viking commodity—for the tusks of four silver walrus heads along the edge of the bowl.

“Crowning the North” was organized by the Houston Museum of Fine Arts but includes several artworks from Mia’s collection for context. An 1894 print by Edvard Munch, the Norwegian artist best known for The Scream, is called Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones). As advertised, it shows two people standing an unusual distance apart, looking straight ahead, riding the psychological line between solitude and isolation.

A Norwegian tapestry from the 1600s depicts “The Wise and Foolish Virgins,” a biblical parable of two sets of maidens at a wedding: one conserving their oil lamps until the groom arrives, the other burning them—only to be left in the dark. A very Norwegian nod to practicality, such scenes were popular in the countryside.

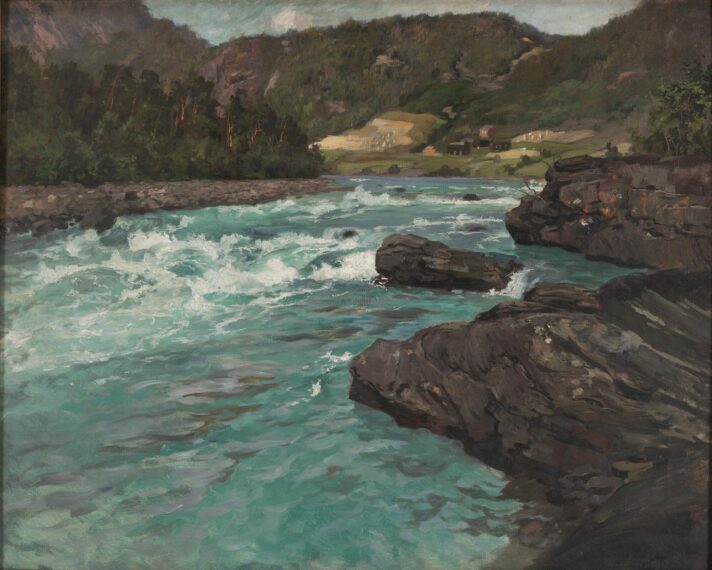

Frits Thaulow (Norwegian, 1847–1906), Green River, 1904, oil on canvas. The Christina N. and Swan J. Turnblad Memorial Fund, 2024.77.2

Indeed, Mia has been quietly adding key Scandinavian artworks to the collection in recent years. Around the corner from the silver show, in Gallery 354, is one of the latest: Norwegian painter Frits Thaulow’s 1904 Green River. Acquired in 2024, it’s a landscape of the Otta River, which runs green from glacial runoff and takes its name from an old Norse word for fear. In Gallery 359, amid other Nordic artworks, is another 2024 acquisition: Ludwig Skramstad’s monumental landscape A Norwegian River in Winter, from around 1880.

Such scenes of natural beauty—forests, fjords, waterfalls—were in high demand in Norway as its drive for independence accelerated. Often set in winter, they suggested something of the country’s character, its quiet strength, its rugged resilience, despite centuries of domination. Like the Dragestil itself, they evoke an ancient claim on a proud heritage.

See the Exhibition & Ice Interpretation

“Crowning the North: Silver Treasures from Bergen, Norway” is on view in Gallery 350 from November 15, 2025, to March 8, 2026. Don’t miss a special ice adaptation of Viking Dragon Boat during the Institute of Ice, kicking off on January 8, 2026.